[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xENEchTFk-E&w=550]

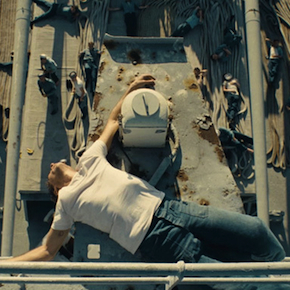

Spoiler Alert! Perhaps you have seen the trailer (theatrical version, above) wherein, to the beat of Joaquin Phoenix’s fist against a window, face down, you hear the voiceover of Lancaster Dodd (played by Philip Seymour Hoffman) reading from his own book:

“Man is not an animal. We are not a part of the animal kingdom. We sit far above that crowd, perched as spirits, not beasts…I’ve unlocked, and discovered, the secret to living in these bodies we now hold.”

It has already been said that Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master is only loosely derived from Scientology’s creator, L. Ron Hubbard, that Hoffman’s character-relation to the man “is almost incidental to the other tasks it is trying to accomplish,” but it is difficult to explain just which tasks those are. Like the Rorschach cards in Freddie Quell’s examination room, the audience knows there’s something more to be divined than an origin story, even a slant-bio (think Capote, The Aviator), but then viewers often find themselves mesmerized when later asked about the film, and the only substantive thing to quickly issue is what you’ve already heard about the Scientology bit. It is less about an occult movement as much as it is about the a-historical occult (the Latin root for which is “hidden, clandestine”) of inner-man, his stretching out to be like a god from the tethered will of his own nature. It is a story about man’s violent dealings with his own bondage.

It has already been said that Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master is only loosely derived from Scientology’s creator, L. Ron Hubbard, that Hoffman’s character-relation to the man “is almost incidental to the other tasks it is trying to accomplish,” but it is difficult to explain just which tasks those are. Like the Rorschach cards in Freddie Quell’s examination room, the audience knows there’s something more to be divined than an origin story, even a slant-bio (think Capote, The Aviator), but then viewers often find themselves mesmerized when later asked about the film, and the only substantive thing to quickly issue is what you’ve already heard about the Scientology bit. It is less about an occult movement as much as it is about the a-historical occult (the Latin root for which is “hidden, clandestine”) of inner-man, his stretching out to be like a god from the tethered will of his own nature. It is a story about man’s violent dealings with his own bondage.

Simply put (a risk in itself), the film revolves around the relationship between Freddie Quell (Phoenix), a 1950s WWII PTSD-blend of alcoholic rage and wandering, and Lancaster Dodd (Hoffman), leader of a self-acclaimed and posse-promoted movement known as “The Cause,” he is The Master, “a writer, a doctor, a nuclear physicist, a theoretical philosopher.” Quell, who we find first drinking tanker oil while overseas; then as a portrait-taker, making makeshift cocktails in the darkroom of a department store; then on a California cabbage farm, poisoning a fellow worker’s booze—seems to epitomize the reach for Dodd’s “Cause.” The two meet when, on the run, Freddie wanders upon a private yacht donated to The Cause, setting sail to New York. Dodd ushers the prodigal into the society, ostensibly to cure him of his impulses, something Freddie admittedly wants—but we also get the feeling that Dodd sees something in Freddie that he longs for in himself. We are given two men who expose in the other their lack: To Freddie, Dodd’s self-mastery; to Dodd, Freddie’s self-evident impulsiveness.

Even this kind of character analysis is insufficient, though. Seymour Hoffman shows splendidly that Dodd is a human being—he loves Freddie’s hooch, and indeed loves it so much his wife (played by Amy Adams) must right him—in more ways than one—to keep him in tow. But his including Freddie is also a righting of his own; if he can master the beast, if he can turn Freddie into one of his own, he is suddenly able to fortify his argument. His prodigal is not welcomed so much as he is implemented for Dodd’s own self-righteousness.

It seems that this is a point of focus for P.T. Anderson, the interplay between man’s distinction from and bondage to The Beast. As much as Freddie wants to believe that Lancaster Dodd’s wisdom will “bring man back to Perfect,” the audience sees the same creaturely violence in them both. When questioned in any way whatsoever about the truths of The Cause, Philip Seymour Hoffman brilliantly emotes an anger in Lancaster Dodd that is truly frightening. His wife is no different; after one such skirmish, she furiously tells her husband, “The only way to defend ourselves is attack.” Anderson in that anger seems to want to distinguish the difference in the virtuous desire to be true and the very creaturely desire to be right. This kind of violence, Anderson seems to be saying, is no different from Freddie’s sexual exploits with a sand-castle mermaid.

There is a scene in which Dodd is arrested for missing funds and taken to the jailhouse, while Freddie is arrested for punching the cops who are attempting to handcuff Dodd. They end up in a jail cell side-by-side, both products of their own forms of violence. Yelling in two despicable tirades at one another, suddenly the two appear just alike. Despite the longings for the contrary, despite the self-justifying convincings to make them true, both men are bound to their creatureliness. In short, one of the main themes of this film is man’s irrevocably bound will.

That is not to say that Paul Thomas Anderson is making a sweeping statement about Scientology, much less paranormal-religious belief in general. The film is actually quite sympathetic, in some ways at least, to the longing for life change, to the efficacy of various forms of introspection for healing. Sure, the “subjection to processing” element of The Cause, wherein the subject is questioned about past experiences, suppressed thoughts and emotions, et cetera, seems questionable in Dodd’s hands: he says “what comes is always right, always right, always good, always helpful.” Still, though, we can see in Freddie’s processing that, in digging into the pain of his past, he sees the truth and, in doing so, is changed.

Healing, getting better, returning to “Perfect,” is an illusion, though, unless it is honest. Freddie understands this, and it is why he is so violently defensive of Dodd—if Dodd is wrong, he thinks, anything I have gained from this therapeutic time in my life is a sham. Similarly, when Dodd’s wife asks her husband whether Freddie is “past help,” Dodd cannot accept it to be true. If it is true, The Cause is false.

The Cause does appear to prove false. Freddie eventually leaves, Dodd appears to the audience an increasingly egomaniacal impostor, but only insofar as he is not able to admit his own humanity. He has a final conversation with Freddie in England, where Dodd has taken a position as a schoolmaster. He invites Freddie to stay with them, to which Freddie seems to balk. Dodd then tells Freddie, “If you ever find a way to live without having a Master, let us know, because you will be first person who ever lived to have done so.”

In the final scene, Freddie, in bed with a woman met in a bar, seems to have made no progress from the time spent in The Cause; he drunkenly slurs over some of the religious “processing” slogans while having sex with her. It is here where we see both men, Dodd and Quell, two men in each man—the fleshly man who cannot, will not help who he is, and the spirit man who longs for more. There’s nothing to be done about it, Anderson seems to be saying, neither two can be shed.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pALMMIoxTzY&w=600]

COMMENTS

One response to “Mockingbird at the Movies: The Master”

Leave a Reply

I had been meaning to see this just for the actors in the Master.Your post pushed me into pulling up Fandango and seeing I had 15 minutes to get to the 3:30 playing.Well,the acting couldn’t have been better,the depravity of humanity couldn’t have been portrayed more as it is.No character was appealing yet I found myself identifying with most all of them.It is rough,we are all fallen ,yet our God died for us anyway.