1. Kicking off this week’s review is a fantastic reflection in the Wall Street Journal by Mike Kerrigan: “A Late Bloomer Learns to Forgive.” A lawyer by occupation, Kerrigan speaks of his long-standing, uncomfortable relationship with forgiveness:

In his autobiographical “Confessions,” St. Augustine of Hippo, whose Feast Day is celebrated Friday, admits praying as a young man, “Lord, make me chaste, but not yet.” By so doing, he became the spiritual role model of late bloomers everywhere.

The petition conveys a timeless truth about the human condition, where often the spirit is willing but the flesh is weak. Still, I’ve wondered: How could such an otherworldly saint have uttered so worldly a prayer?

Centuries after St. Augustine’s time, Oscar Wilde answered the question well: The only difference between saints and sinners is that every saint has a past and every sinner has a future. We can always be better tomorrow. Of course, tomorrow never comes for some. Or it comes but, when it does, choosing the hard right over the easy wrong has lost its appeal. […]

Grudges have been useful in my adult life as well, or so I thought. I convinced myself life’s wrongs — no slight too small — are kindling to fuel my competitive fire, and winning ultimately leads to joy. I see now that it doesn’t. Not the lasting kind, anyway.

The more tomorrows become today, the more I realize it isn’t firm justice I want, but tender mercy I need. The forgiveness I show is the only forgiveness I can hope to receive, no more and no less. I’ve got work to do.

Inspired this day by St. Augustine, and mindful that late bloomers must bloom sometime, I pray: Lord, make me merciful. Not tomorrow, today.

2. Rolling Stone wrote a moving and profound tribute to the singer-songwriter Justin Townes Earle, who died last week of a suspected overdose. Earle sang of a burden he couldn’t shake and a yearning for grace and forgiveness that cuts to the heart:

From “Yuma” to his final album, 2019’s The Saint of Lost Causes, Earle’s music was preoccupied with repentance and absolution. A former addict who would struggle with relapse on and off throughout his adult life, Earle wrote songs that refused to moralize his fellow miscreants. Those songs, like 2008’s “Who Am I to Say,” in which a narrator spends three minutes letting a woman off the hook for her transgressions, were like prayers — as if Earle were hoping that if he practiced enough radical forgiveness in his art, someone might eventually forgive him too. […]

More often, though, he wrote songs about men and women who were always warning those around them that their burdens might just get the best of them — that nothing was going to change the way we feel about them now.

If Earle’s characters weren’t warning each other preemptively about what they were about to do (“Won’t Be the Last Time”), they were apologizing for their misdeeds just after the fact (“Someday I’ll Be Forgiven for This”). On 2010’s “Slippin’ and Slidin’,” Earle turned the promise of Little Richard’s riotous 1956 rocker into a sorrowful self-scold: “I shoulda learned better,” he sings, assuming the character in the midst of a relapse that he himself would suffer through the very month the song was released. […]

But it’s the album’s penultimate song, “Ahi Esta Mi Nina” (loosely translated as “there’s my girl”), where Earle would reveal, for the last time, his most shining self. The song chronicles yet another difficult conversation between parent and child, much like the phone call to mom in “Yuma.” But this time, it’s the parent pleading for forgiveness: A wayward father is speaking with his estranged daughter after years of abandonment.

“I’ll just say, ‘I’m sorry,’” he tells her toward the end of the song, “But I know it’s not as simple as that.”

By that point, it’s not clear if the daughter is even physically present for the conversation, that the father hasn’t imagined this entire exchange in his head. But Earle knows that is beside the point. By apologizing, the father can keep moving, even if all he’s done is forgive himself.

3. “I hope this post finds you well!” “Stay safe!” “It could be worse!” This week featured two articles on the widening gap between the positivity we project and the reality of pandemic life. The social convention of “putting on a happy face” may be less consequential in normal times, but nowadays they feel increasingly oppressive. Whether it be emails/conversations or just our outlook on life, we (particularly Americans) tend toward an optimism that doesn’t seem to be helping:

[A]s well intentioned as those who lean on such phrases may be, experts are cautioning against going overboard with the “good vibes only” trend. Too much forced positivity is not just unhelpful, they say — it’s toxic.

“While cultivating a positive mind-set is a powerful coping mechanism, toxic positivity stems from the idea that the best or only way to cope with a bad situation is to put a positive spin on it and not dwell on the negative,” said Natalie Dattilo, a clinical health psychologist with Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “It results from our tendency to undervalue negative emotional experiences and overvalue positive ones.” […]

Denying, minimising or invalidating those feelings through external pressure or your own thoughts can be “counterproductive and harmful,” Dattilo said.

“‘Looking on the bright side’ in the face of tragedy of dire situations like illness, homelessness, food insecurity, unemployment or racial injustice is a privilege that not all of us have,” she said. “So promulgating messages of positivity denies a very real sense of despair and hopelessness, and they only serve to alienate and isolate those who are already struggling.”

Internalising such messages can also be damaging, she said.

“We judge ourselves for feeling pain, sadness, fear, which then produces feelings of things like shame and guilt,” she said. “We end up just feeling bad about feeling bad. It actually stalls out any healing or progress or problem solving.”

Research has shown that accepting negative emotions, rather than avoiding or dismissing them, may actually be more beneficial for a person’s mental health in the long run. One 2018 study tested the link between emotional acceptance and psychological health in more than 1,300 adults and found that people who habitually avoid acknowledging challenging emotions can end up feeling worse.

4. As weeks of COVID-19 closures have turned into months, boredom is becoming our daily companion. So much so that the New Yorker devoted a whole article to the subject. Definitions abound, ranging from “a desire for desires” (Tolstoy) to a general feeling of malaise (Heidegger). Christians used to call boredom acedia, a “bodily listlessness and yawning hunger as though he were worn by a long journey or a prolonged fast. [Looking] at the sun as if it were too slow in setting.” Sound familiar? And while boredom has typically been categorized as a vice to be avoided, research psychologists believe the experience is profoundly human, our default experience when left alone to our devices. One may say that we are, by nature, bored creatures:

Danckert and Eastwood argue that “boredom occurs when we are caught in a desire conundrum, wanting to do something but not wanting to do anything,” and “when our mental capacities, our skills and talents, lay idle — when we are mentally unoccupied.”

Erin Westgate, a social psychologist at the University of Florida, told me that her work suggests that both factors — a dearth of meaning and a breakdown in attention — play independent and roughly equal roles in boring us. I thought of it this way: An activity might be monotonous — the sixth time you’re reading “Knuffle Bunny” to your sleep-resistant toddler, the second hour of addressing envelopes for a political campaign you really care about — but, because these things are, in different ways, meaningful to you, they’re not necessarily boring. Or an activity might be engaging but not meaningful — the jigsaw puzzle you’re doing during quarantine time, or the seventh episode of some random Netflix series you’ve been sucked into. If an activity is both meaningful and engaging, you’re golden, and if it’s neither you’ve got a one-way ticket to dullsville. […]

Are we more bored since the advent of ubiquitous consumer technology started messing around with our attention spans? Are we less able to tolerate the sensation of being bored now that fewer of us often find ourselves in classically boring situations — the D.M.V. line or a doctor’s waiting room — without a smartphone and all its swipeable amusements? A study published in 2014, and later replicated in similar form, demonstrated how hard people can find it to sit alone in a room and just think, even for fifteen minutes or less. Two-thirds of the men and a quarter of the women opted to shock themselves rather than do nothing at all, even though they’d been allowed to test out how the shock felt earlier, and most said they’d pay money not to experience that particular sensation again. (When the experiment was conducted at home, a third of the participants admitted that they cheated, by, for example, sneaking looks at their cell phone or listening to music.)

5. Schools are beginning to reopen around the country and universities are (understandably) holding their breath, hoping to avoid outbreaks of COVID-19 on campus. The experiment so far has largely been unsuccessful, but not because colleges haven’t tried hard enough. While some may blame college students for the spread, the real culprit turns out to be a familiar nemesis: human nature and low anthropology. The debacle feels a whole lot like an Onion article happening before our eyes. As reported by Inside Higher Ed, it turns out that telling college students what to do doesn’t really work.

[A]sking students — especially those who are 17 or 18 years old — to “be adults” neglects decades of research on how young people evaluate risks and rewards. Kenneth Elmore, associate provost and dean of students at Boston University, called such messages “incredibly condescending and not motivating” for students to follow the rules. […]

Laurence Steinberg, a professor of psychology at Temple University and a leading expert on adolescent behavior, said young adults tend to think more of “immediate rewards rather than long-term consequences,” and they have a unique need to socialize with others. Even if college-aged people understand the risks and consequences for breaking COVID-19 rules, they also tend to believe they won’t get caught, Steinberg said. Strong punitive approaches to bad behavior, such as those employed by Syracuse, Vanderbilt University, Purdue University and others last week, are “futile” and “not likely to work,” he said.

“When you have a temptation that is very immediately enticing, especially at this age, you often behave in a way that sets aside what you know you should be doing,” Steinberg said. […]

Marcus, the Harvard epidemiologist, has researched HIV prevention and promotion of sexual health. She said punitive public health efforts “don’t deter high-risk behavior — they tend to drive that behavior behind closed doors.” […]

Elmore said he’s “got my fingers crossed” that Boston University’s positive campaign will be effective in preventing such situations.

“I may be naïve, but I’ve been at it for a long time,” he said. “I know what motivates young people, and they don’t need a bunch of old people wagging their fingers at them. They don’t tend to listen to that.” […]

Griffith, the senior at UNC Chapel Hill, was discouraged about the coronavirus outbreaks on her campus last week and wondered whether if it might be better for other campuses to remain closed. She said colleges can do everything right to prevent students from breaking the rules, but it only takes a few people to get infected for the whole population to be exposed to the virus.

“Even with the enforcement strategy, that may not even be enough,” Griffith said. “Maybe it’s best for people to stay home.”

6. In humor this week, the Hard Times laments, Gym Closures Leave Old Guys With Nowhere to Shower. Elsewhere, McSweeney’s asks, “Is This How Running is Supposed to Feel?“: “The only thing keeping me going is that, if I stop, I get the sense you’re going to judge me a tiny bit.” And Part 3 of their “Nihilist Dad Jokes” is as funny as it is dark:

I’m so good at sleeping, I can do it with my eyes closed!

Each night is a dress rehearsal for my inevitable fall into the abyss of eternity.

And each day I walk closer to the precipice while distracting myself with an office job that doesn’t matter, a family who treats me like an oaf, and an inane ritual of watching spandex-clad men give each other brain damage.

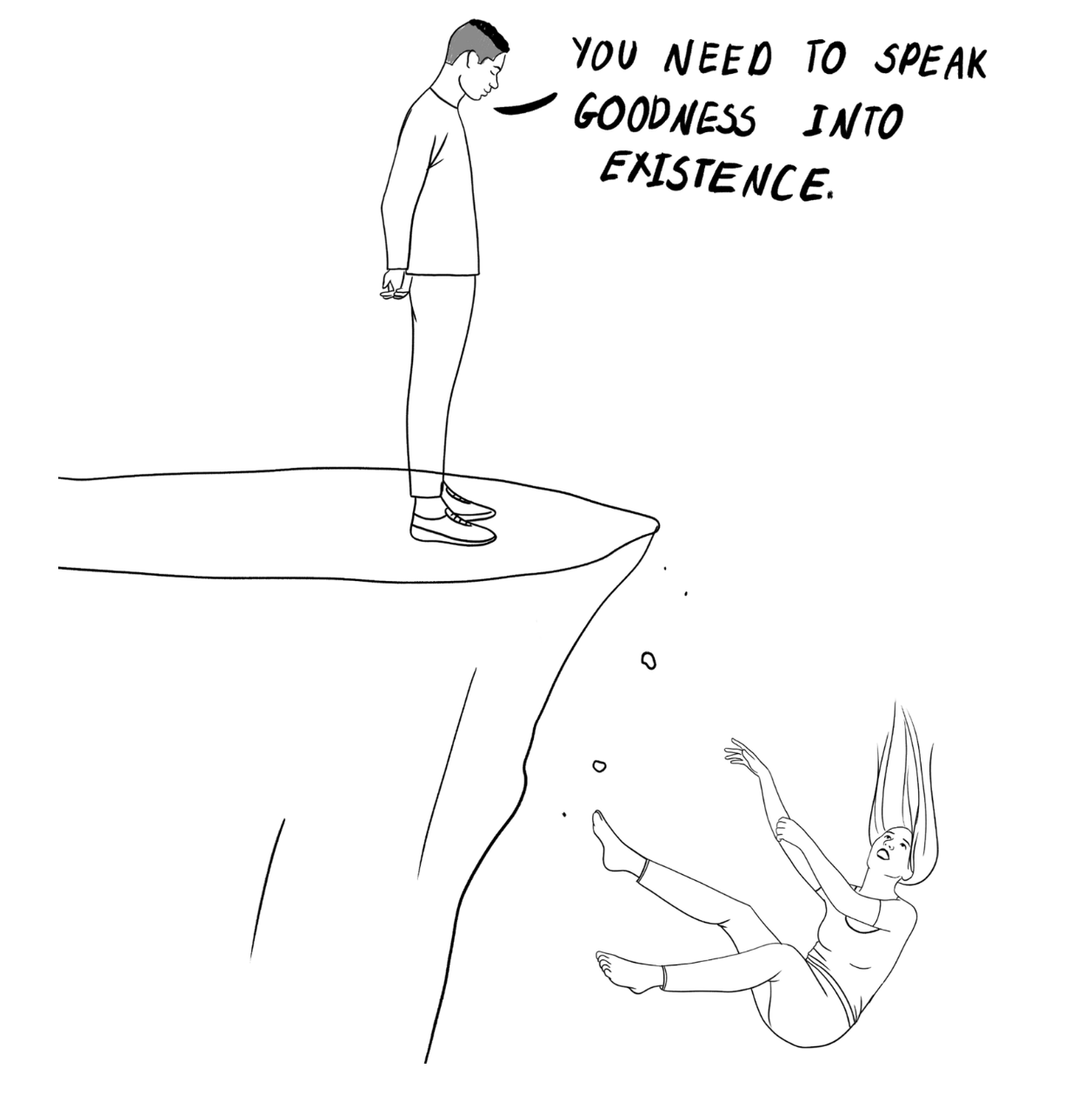

Photos this week come from the New Yorker‘s hilarious and absolutely true “This is What Your Unsolicited Advice Sounds Like.”

Strays

- Nadia Bolz-Weber was on Dax Shepherd’s enormously popular Armchair Expert podcast, talking about sobriety, faith, community, Jesus, and DZ’s book, Seculosity(!).

- Over at the A.V. Club, comic books and Christian Theology have combined in spectacular fashion to depict The Harrowing of Hell, by Evan Dahm.

- Mere Orthodoxy highlights the minimalism of Marie Kondo (and others) and its deceptive parallels with Jesus’ call to discipleship.

- What did the church of Ethiopia have to do with the Reformation in Germany? Quite a bit, writes Jennifer Powell McNutt over at Christianity Today.

Sign up for the Mockingbird Newsletter

Sign up for the Mockingbird NewsletterCOMMENTS

Leave a Reply