1. It’s not every week we get to witness such a stunning display of capital-F Forgiveness, so let’s savor this one. I’m referring to Brandt Jean’s overture to his brother’s killer, Dallas police officer Amber Guyger at her sentencing:

As far as I can tell, the clip makes everyone cry when they first watch it, such being the nature of the human heartstrings. But after the shock wears off, it’s uncanny (and more than a little tragic) how quickly the peanut gallery sets to work finding reasons to take issue. Some protestors focus on the racial element–and clearly something about the reaction signals the extent to which whites are dying for blacks to forgive or punish them (and the extent to which we could all learn from Black Christians on this subject)–others on the justice element, some on the theological (cheap grace!). But in all truthfulness, I’ve never seen an act of forgiveness this bold not provoke major resistance, regardless of the dynamics involved. As a wise man once wrote in his Panopticon:

There is something upsetting about the 100%-with-no-exceptions forgiveness that Jesus talked about. It is a feature that upsets conservatives. But it also upsets liberals. There is something in it to offend everybody. Except the person who needs it at the time.

CJ explored the anti-forgiveness bias in his excellent recent piece about Taylor Swift. And perhaps my all time favorite on the subject is Ethan’s incredible essay, “The Losing Economy of Forgiveness” which was featured in the Forgiveness Issue of our magazine. I stand by this one too.

2. On a somewhat related note, the best thing I read this past week came from Episcopal minister Heidi Haverkamp, who penned an essay for Christian Century on “How I Learned to Love Total Depravity.” Not exactly a dinner-party-approved topic, her explanation of the link between compassion and ‘low anthropology’ is as compelling–and courageous–an attempt as I’ve come across in quite some time. Every word is worth your time, but here are few portions:

As an adult and a Christian, I want to do the right thing. I keep mental lists of how I want to live more responsibly: eat less meat, recycle, call my representatives, buy less plastic, reduce my carbon footprint, speak up about racism, give to charities, show up at community police meetings. But it never seems like enough. Social media is always ready to help me count the ways I could do more, leaving me feeling more guilty than righteous, unable to keep up. As Paul writes, “I can will what is right, but I cannot do it”—at least not consistently or very effectively. No matter what I do or how hard I try to be righteous, the world spins me to my knees at every turn with more evidence of cruelty, catastrophe, and waste.

I do not feel theologically equipped to handle the enormous weight of evil I see in the world. After all, I was raised to believe that humans are capable of stopping it…

Total depravity frames humans not as good people who sometimes mess up but as messed-up people who, with God’s help, can do some good things—but nothing completely free of selfishness or error. We are unable to make a choice that is unquestionably, entirely good. None of our actions, loves, or thoughts can be truly without sin.

I find a surprising grace in the bleak, unflinching outlook of my Calvinist heritage. Total depravity matches the sin-sized hole in my belly in a way that “all people are basically good” never could.

Total depravity speaks to sin in our personal lives. More importantly for me, it also gives theological definition to corporate and societal sins. It’s not just that I am unable to love everyone I meet or to live a life that is plastics-free. I have also found it impossible to untangle my individual life from systems of injustice—institutionalized racism, pollution of the air and land and water, cheap clothing and food supplies that depend on the exploitation of laborers, banks and corporations that bend the economy toward their profit. A contemporary Episcopal prayer of confession includes this line: “We repent of . . . the evil we have done, and the evil done on our behalf.” There is a lot of suffering and a lot of evil in this world, and I find I cannot consider myself entirely innocent of it.

It’s just that the more I make the salvation of the world a rational, solvable problem, the deeper I seem to sink into futility. But when unreasonable, unremitting human sin is something I expect, then I can face the headwinds of evil without despair. When I believe that human life—including my own—will never be without sin and suffering, I have a greater ability to tolerate pain and horror and to keep on doing justice, loving kindness, and walking humbly. I can, as Anne Lamott would say, keep singing “Hallelujah!” and looking for grace anyway.

3. On the Seculosity front, writing in Town & Country, Mike Albo describes “How Spiritual Snobs Became the New One Percent”. He’s interested primarily in how enlightenment has been annexed by the Influencer crowd, the way it’s become a new status symbol about which to #humblebrag. He presents it as an outgrowth of the seculosity of wellness, i.e. what happens when aspirational branding becomes more ‘holistic’ (but no less lucrative!). I found his comments on the almost-medieval hierarchy at work to be especially germane:

Aristocratic mysticism is nothing new (see: Rasputin and the Romanovs), but now ascetic pursuits have been paired with the ability to self-broadcast more than ever before, and self-actualization has become both a branding tool and bragging right.

“Ten years ago we didn’t document every green juice we drank,” says Melisse Gelula, co-founder of the lifestyle site Well+Good. “It’s infiltrated our lives. We all have to ask ourselves, ‘Am I doing this to feel better or to share that I am feeling better?’ ” (On Well+ Good’s trend list for 2019 is “performative wellness”—the act of looking as though you are centered.)…

The guru gold rush has created a growing caste system of monks, healers, and guides. At the top, of course, are Oprah and the Dalai Lama, but if you can’t get near these supremes, there are those who have met them, or at least have taken selfies with them. Gabby Bernstein, a “spirit junkie” and Lululemon global yogi, created May Cause Miracles weekend workshops that “offer an exciting plan to release fear and allow gratitude, forgiveness, and love to flow through us without fail.” Motivational speaker and “unshakable optimist” Marie Forleo offers a way for you to create success that speaks to your soul to “get anything you want.” Their pictures with Oprah are stamped on their sites like a Consumer Reports seal of approval…

It’s a pretty stinging indictment, so I was surprised he closed it on such a, well, empathetic note:

Perhaps the most important insight that our modern, self-promoting search for a higher power offers [is that] everyone wants divine intervention; it’s just that some are willing to pay anything to try to get close to it. Celebrities: They’re desperate, just like us.

4. At The New Yorker, building on Tavi Gevinson’s excellent essay about Instagram, Carrie Battan traces “The Rise of the Getting Real Instagram Post”. The law recalibrated is still… the law:

Celebrities have always used their social-media accounts as confessional booths, but at some point in the past year Instagram stars began interrupting their otherwise aspirational feeds with a very specific type of revelation—posts that could be described as the “getting real” moments. For many beauty and fashion personalities, the “getting real” moment is about mental health and well-being. An exemplar of the form came in late 2018, from the French street-style icon and fashion blogger Garance Doré. “These last years have been bumpy to say the least,” she wrote in a caption. The text, sombre and unusually long, sat below a no-makeup photo of Doré, perched outdoors in hiking clothes, looking pensive. “What’s funny is that when I look back, I started these years in the mirage of the fashion girl, living the ‘high life’ (dumb expression). Truth is, after a few years of exploring that world, I became miserable and I felt very far from myself.

“Getting real” posts vary widely in their substance, but their tone is meant to signal a moment of catharsis. I have been living a lie, the Instagrammers explain, as if their followers had been naive enough to take prior posts at face value. At their best, these posts offer moments of relief to the follower—not to mention a voyeuristic jolt. But there is plenty of deception, if not delusion, in them, too. Most of them sidestep the inconvenient fact that distress is an occupational hazard of life online. Although Instagram has been well documented as one of the most demoralizing places on the Internet, it’s easier to post about insecurity and isolation as if they flowed solely from external factors, rather than from the powerful, consuming platform by which many of these people make their livelihood. Indeed, at their worst, such posts pull the same trick as aspirational content: they leverage insecurity for profit…

What made Gevinson’s essay so compelling was that she admits to having always tried to be relatable—and, in her analysis, that effort had only twisted her into deeper knots of deception. “Getting real,” it turned out, was not a corrective. It was another ruse, designed to appeal to an audience, and used to brush aside the mess.

5. A timely, wide-ranging essay “On Living” by Alan Noble on Medium, in which the author of Disruptive Witness surveys our ever-evolving relationship with mental health, both as a culture and a Church. As the title suggests, he is making a case for life as opposed to death, speaking with deep compassion but also real conviction about the reality of suicide. I hope he develops this further:

Living in a society governed by technique inclines us to imagine life is easier than it ever is. Technique is the use of rational methods to maximize efficiency, and we see it everywhere: Time saving technology, apps that maximize our workouts, medicines that drown out irrational thoughts, ubiquitous entertainment in our pockets, and scientifically proven methods for parenting, working, eating, shopping, budgeting, folding clothes, sleeping, sex, dating, and buying a car. The promise of technique is that we are collectively overcoming all the challenges to life through research, technology, and discipline. All you have to do is find the right self-help book or life-hack or app or life coach or devotional.

And this is exactly why technique’s promise that life is easier than ever becomes just another source of dread: if life doesn’t have to be this hard, if there are answers and methods and practices that can solve my problems, then it’s really my fault that I’m overwhelmed or a failure. Sure, systems can be corrupt, nobody is perfect, and not everyone is born with the same gifts, but we have methods for overcoming these hindrances. So if I am not living to my full potential, I am to blame…

Your existence is a testament, a living argument, an affirmation of creation itself… even when our minds deceive us into hopelessness, we cannot shake the intuition that life is still precious. Perhaps we cannot sense the preciousness of our own lives, but the lives of our loved ones inherently feel sacred. We love them and feel the goodness of their existence even when we can’t feel the goodness of our own. Then we must remember that the decision to scorn the goodness of life by ending our own is always an invitation for others to follow suit.

Usefulness is the sole criterion for the World, the Flesh, or the Devil. But you have no use value to God. You can’t. There is nothing He needs. You can’t cease being useful to God because you were never useful to begin with. That’s simply not why He created you and why He continues to sustain your being in the world. It was gratuitous, prodigal. He made us just because He loves us and for His own good pleasure. Every other reason to live demands that you remain useful, and one day your use will run out. But not so with God. To God, your existence in His universe is an act of creation, and it remains good as creation even in its fallen state.

6. Finally, “wokeness” has come in for a pretty serious bruising this past week. In addition to his viral rant about white shame, Mr. love-to-hate-him himself Bill Maher gave a prescient-but-characteristically-irritating interview to the NY Times Magazine on the subject but the more insightful bit of criticism imho came from Stephen Marche in The Atlantic:

The Trudeau scandal points to a larger problem: The woke will always break your heart. It’s not just that nobody’s perfect, and it’s not just that times change, and it’s not even that the instinct to punish that defines so much of the left is inherently self-defeating. If people want to sell you morality, of any kind, they always have something to hide.

‘Any kind’ might be a bit strong, especially if your morality makes room for grace, but still, it’s becoming increasingly hard to pretend not to know what he’s talking about.

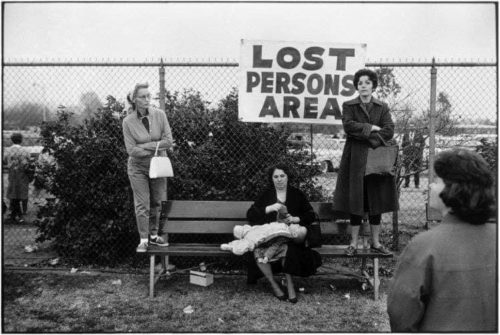

Lost Persons Area, Pasadena, California. c.1963 by Elliott Erwitt

Strays

- Not just an American problem: A surge in anxiety and stress is sweeping UK campuses.

- Two of our favorite wordsmiths collide in Meghan O’Gieblyn’s review of Leslie Jamison’s new essay collection, Make it Scream, Make it Burn.

- As the videos in the post indicate, I currently can’t get enough of I DON’T KNOW HOW BUT THEY FOUND ME.

- A Game Like Heroin: On Escapism, TwitchCon, and Kicking the ‘Fortnite’ Habit by Mitchell Duran

- Lastly, Chad Bird and I are speaking at the Crossings conference in late Jan (1/26-29) and would love to have you join us. Click here for more info.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply