1. This first one is an absolute treasure, well deserving of a post of its own. I’m referring to “One Man’s Quest to Change the Way We Die” by Jon Mooallem in The NY Times Magazine. Mooallem profiles doctor and triple amputee B.J. Miller, who has become well-known for the unconventional and rather Buddhistic approach to palliative care he’s pioneered at a hospice in San Francisco. To these ears, however, Miller’s story and vocation brim with what can only be called grace in practice. Meaning, his is a case in which the experience of grace–of being loved at your darkest/ugliest/most despondent–births a passion for caring for others at theirs, and in a thoroughly non-coercive manner. But that’s not all. Miller’s wounds represent not only the means of his own ‘liberation’ but the channel through which he reaches his patients. If it sounds somewhat Christ-like, well, a friend notes mid-way through: “it’s impossible to describe what it feels like to be with [Miller]. People feel accepted. I think they feel loved”. I’ve reproduced a few paragraphs below but cannot recommend the whole piece enough. (The story of Randy Sloan, the retrofitted motorcycle, and the wedding-funeral, has divine fingerprints all over it). Grab your tissues:

For a long time [after the accident in which Miller lost both legs and one of his arms], no visitors were allowed in his hospital room; the burn unit was a sterile environment. But on the morning Miller’s arm was going to be amputated, a dozen friends and family members packed into a 10-foot-long corridor between the burn unit and the elevator, just to catch a glimpse of him as he was rolled to surgery. “They all dared to show up,” Miller remembers thinking. “They all dared to look at me. They were proving that I was lovable even when I couldn’t see it.” This reassured Miller, as did the example of his mother, Susan, a polio survivor who has used a wheelchair since Miller was a child”…

He resolved to think of his suffering as simply a “variation on a theme we all deal with — to be human is really hard,” he says. His life had never felt easy, even as a privileged, able-bodied suburban boy with two adoring parents, but he never felt entitled to any angst; he saw unhappiness as an illegitimate intrusion into the carefree reality he was supposed to inhabit. And don’t we all do that, he realized. Don’t we all treat suffering as a disruption to existence, instead of an inevitable part of it? He wondered what would happen if you could “reincorporate your version of reality, of normalcy, to accommodate suffering.”… This was the only way, he thought, to keep from hating his injuries and, by extension, himself…

“Parts of me died early on,” he said in a recent talk. “And that’s something, one way or another, we can all say. I got to redesign my life around this fact, and I tell you it has been a liberation…”

There’s an emphasis [at his hospice] on accepting suffering, on not getting tripped up by one’s own discomfort around it. “You train people not to run away from hard things, not to run away from the suffering of others,” Miller explained. This liberates residents to feel whatever they’re going to feel in their final days, even to fall apart…

Yes, [Miller’s approach is] about wresting death from the one-size-fits-all approach of hospitals, but it’s also about puncturing a competing impulse…: our need for death to be a hypertranscendent experience. “Most people aren’t having these transformative deathbed moments,” Miller said. “And if you hold that out as a goal, they’re just going to feel like they’re failing.”

“I’m letting [my patients] know I see their suffering,” he said. “That message helps somehow, some way, a little.”

2. On the opposite side of the law-grace equation, but no less lengthy (sorry!), I don’t know how we missed Josh Cohen’s “Minds Turned to Ash” when it appeared on The Economist’s 1843 site back in July. Cohen, a psychoanalyst and writer, gives an stunning account of burnout, its symptoms and causes. In his professional experience and opinion, people burn out not because they’re trying to do too much (though that doesn’t help), but because of the anxiety, or existential weight, we have collectively foisted on our “doing”. Or you might say, because of the way our culture conflates action with performance. It’s a penetrating indictment of the cult of productivity, one which doubles, of course, as a harrowing description of works righteousness, of how the law operates on the sinner. Hidden in there too is a pretty incredible example of how we turn grace into its opposite, ht CB:

We commonly use the term “burnout” to describe the state of exhaustion suffered by the likes of Steve. It occurs when we find ourselves taken over by this internal protest against all the demands assailing us from within and without, when the momentary resistance to picking up a glass becomes an ongoing state of mind… The exhaustion experienced in burnout combines an intense yearning for this state of completion with the tormenting sense that it cannot be attained, that there is always some demand or anxiety or distraction which can’t be silenced…

Burnout increases as work insinuates itself more and more into every corner of life – if a spare hour can be snatched to read a novel, walk the dog or eat with one’s family, it quickly becomes contaminated by stray thoughts of looming deadlines. Even during sleep, flickering images of spreadsheets and snatches of management speak invade the mind, while slumbering fingers hover over the duvet, tapping away at a phantom keyboard.

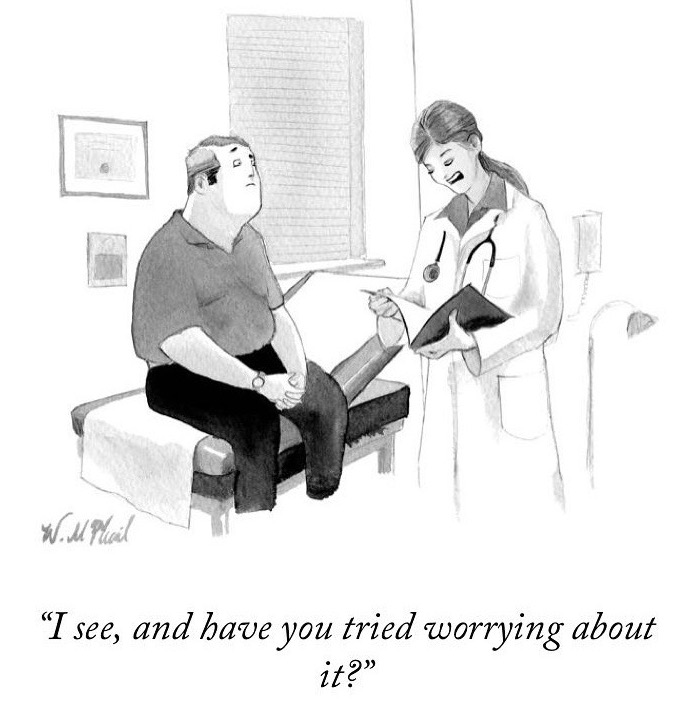

Some companies have sought to alleviate the strain by offering sessions in mindfulness. But the problem with scheduling meditation as part of that working day is that it becomes yet another task at which you can succeed or fail. Those who can’t clear out their mind need to try harder – and the very exercises intended to ease anxiety can end up exacerbating it.

Electronic communication and social media have come to dominate our daily lives, in a transformation that is unprecedented and whose consequences we can therefore only guess at. My consulting room hums daily with the tense expectation induced by unanswered texts and ignored status updates. Our relationships seem to require a perpetual drip-feed of electronic reassurances, and our very sense of self is defined increasingly by an unending wait for the verdicts of an innumerable and invisible crowd of virtual judges…

In previous generations, depression was likely to result from internal conflicts between what we want to do and what authority figures – parents, teachers, institutions – wish to prevent us from doing. But in our high-performance society, it’s feelings of inadequacy, not conflict, that bring on depression. The pressure to be the best workers, lovers, parents and consumers possible leaves us vulnerable to feeling empty and exhausted when we fail to live up to these ideals.

Psychoanalysis is often criticized for being expensive, demanding and overlong, so it might seem surprising that [people suffering from burnout would] chose it over more time-limited, evidence-based and results-oriented behavioural therapies. But results-oriented efficiency may have been precisely the malaise they were trying to escape. Burnout is… the body and mind crying out for an essential human need: a space free from the incessant demands and expectations of the world.

3. As we’re fond of pointing out, given such a context, notions like propitiation and absolution may not be so quaint after all. Unfortunately, if the church is seen as a no-go in the burden-lifting department, we will look elsewhere, for example, the 10th annual “Good Riddance Day” festivities which took place in Times Square last week, ht JE:

Participants wrote down unpleasant, painful, or embarrassing memories from the past year and chucked them into an industrial-strength shredder. Organizers said it’s a good way to start the new year with a clean slate… “This is a chance to detox in a big way,” said Times Square Alliance President Tim Tompkins… “We have a sledge hammer. Sometimes people come and they want to destroy something physically like an old cell phone that’s driving them crazy.”

4. In humor, while the show itself may be notoriously spotty, the season opener of It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia “The Gang Turns Black” was really quite something–high concept, low anthropology (to say the least), ridiculously funny, and genuinely subversive without clapping itself on the back. Maybe not the caliber of Atlanta‘s “B.A.N.” but not that far off either. Web-wise, over at The New Yorker, Susanna Wolff gave us an amusing list of More Reasonable New Year’s Resolutions for 2017 and Bess Kalb pulled together “A Selection of the 30 Most Disappointing Under 30”, for example:

David Saperstein, twenty-six

Shared an article about fatalities in Syria accompanied by the comment “So many feels.”

Elsewhere, The Babylon Bee has been on a bit of tear, with a recently unearthed op-ed by puritan Jonathan Edwards, “Oh, You Made Resolutions? That’s Cute.” And then “Local Calvinist Suspicious Of Any Sermon Mentioning God’s Love” which we mentioned on the Mockingcast.

5. Here at the office, we’re currently putting the finishing touches on the Food & Drink issue of the magazine. Cannot wait for people to read it! By way of appetizer, though, the essay that Jesse Maceo Vega-Frey wrote for The Boston Review, “Pigs”, makes for some incredible reading. What begins as a slightly Portlandia-ish riff on sustainability and conscience in urban farming bumps up against something all too familiar/unavoidable. But it’s the language Ms. Vega-Frey gives this dynamic that got me, namely, the potential divergence between “the ethical and the sacred”. Check it out, ht MG:

We had tried to be responsible consumers of meat as a commodity by buying the flesh of humanely raised animals, but we had never borne the personal burden of consuming meat as a being, of killing to eat, and we felt there was something deep and undeniable, even inexcusable, about this contradiction… I didn’t want to convince myself that killing for food was ethical by reading, arguing, or philosophizing. I felt that I needed to know if it could feel ethical, feel sacred, in my heart…

A few weeks after the killing [of the pigs they’d raised], I brought home a pork shoulder to prepare my chancho hornado for Christmas Eve, a family tradition. Cutting shallow slits around the meat, my clumsy fingers stuffing them with garlic, herbs, and lime juice, swells of appreciation, shame, resignation, and pride moved through me… in the preparation, I felt intimately closer to an understanding of life and culture, to community and my place on this earth, than ever before. It was nearly overwhelming.

In this moment of connection, my heart was confronted with an undeniable paradox: the experience felt sacred but it still didn’t feel ethical. It had never occurred to me that these two things might be separate, that the moral quality of our actions might have little to do with our spiritual sense of interconnectedness to “life,” to our place in the cosmos, to culture. Standing there, I had a shimmering feeling that our ethical sensitivity might actually be the thing which most beautifully and painfully magnifies the distance between ourselves and nature…

6. Next, the best review of Scorcese’s Silence I’ve read thus far–i.e. the one that takes the theological questions raised in the film as seriously as the aesthetic and political ones–comes from Elizabeth Bruenig in The Washington Post:

I don’t think the final point of “Silence” is that apostasy is sometimes approved by God. The message is even more difficult to accept: Apostasy is sometimes forgiven by God. That the creator of the universe would love weak and fragile creatures so much as to forgive their direct rejection of him is, indeed, shocking — but it is also the promise of the faith. That it requires so much convincing to get across more than justifies Endo’s novel and Scorsese’s beautiful film.

Christopher Orr in The Atlantic claims that Silence Is Easier to Admire than Love. But what struck me most was the contrast he offered mid-way through:

Garfield’s previous major role of the year, Hacksaw Ridge, is illustrative. In it, as in Silence, he plays a devout Christian—one who served as an Army medic in World War II and, despite his refusal to carry a firearm, rescued 75 of his gravely injured comrades from the battlefield. But in Hacksaw Ridge, this Christian spirit was emphatic, uplifting, a source of near-limitless strength. It was the solution to the problem at hand. In Silence, by contrast, Garfield faces the far heavier challenge of grappling with the possibility that it might be the problem. Far from saving lives, Rodrigues’s faith is costing them.

7. Those reviews reminded me of an article in The Wall Street Journal ruminating on the strange timelessness that emanates from Donatello’s sculpture of the “Penitent Magdelene”:

This dour carved wooden figure suggests that we put aside our admiration for the wonders of Italian Renaissance art to concentrate on devotion and personal anguish. This is not the Magdalene who wiped Jesus’ feet with her hair. It’s more likely the Magdalene who witnessed the Crucifixion. Or maybe not.

8. Finally, Samuel James makes the claim that “The Hyper-Examined Life Is Not Worth Living in 2017”. While I’m not sure any of us “hyper-examine” anything by choice (or because we do or do not possess the sufficient faith/confidence/knowledge), I found the piece surprisingly heartening. It certainly dovetails with The Economist piece above (#2):

The hyper-examined life is what happens when a legitimate desire to be self-aware becomes an unhealthy preoccupation with our own emotional lives. Hyper-introspection can make us watch our thoughts and feelings with an obsessive hawkishness, making us perpetually unable to enjoy moments of self-forgetfulness…

The effect here is that we fail to cultivate genuine moments of life that don’t have to rebound back to us in the form of digital approval… Many writers and teachers have observed that my generation struggles with decision-making. Millennials often seem paralyzed by fear of failure… Thus, many young people unwittingly hurt their chances of lasting marriages, stable careers, and fruitful relationships by trying to constantly make the “right” decision, when simply making a decision would, in fact, be the right move… such preoccupation with self is exactly what tends to kill happiness in the first place.

By contrast, the well-examined life is not driven by fear or compulsive self-searching but by a humble desire for grace. Personal failures are not meant to be endlessly agonized over but repented of, with confidence in God’s provision for forgiveness and transformation (2 Cor. 7:10). Confidence in the mercies of God disarms paralyzing fear, if we live life knowing that poorly made or even sinful decisions don’t exist outside the scope of God’s plans and promises for us.

For a compassionate counterpoint to all the discussion/jokes/etc about Millennials, the following interview with Simon Sinek has been making waves, and justifiably so:

Strays

- A contentious yet illuminating review of the new book about Norman Vincent Peale.

- Wrestling fans take note: Ric Flair deadlifts 405 pounds, continues to be the man.

- Apparently there’s such a thing as a professional Simon Says caller.

- New Shins single is great. George Michael, RIP.

- Books just for grown-ups! Liana Finck never ceases to amaze.

- Wesley Hill followed up his wonderful post from last year on “The Strange Kingship of Epiphany” with a stirring reflection on “Cruciform Epiphany” for The Living Church.

- Very excited about the Dallas event next Friday and Saturday – schedule here. It’s free!

COMMENTS

One response to “Another Week Ends: Amputee Palliatives, Burnouts, Good Riddance Day, Pig Ethics, Silence and the Penitent Magdalene”

Leave a Reply

To be The Man, you gotta beat The Man!