The vast majority of Protestant Christians agree (1) that good works are not necessary to salvation and (2) that doing good works is good. But Protestant preaching and writing about works varies wildly. At least two reasons for that variance are different theories of how people change and different ideas about what the motive of good works should be. This is the second of a several-part series comparing common motivators deployed in pulpits and Sunday school classrooms with those of the New Testament epistles.

Every Sunday, I experience a wash of guilt and resolve to do better. Sundays, of course, are when iPhones send out the weekly report for average daily screentime that week. Hours of every day that week (and it’s always hours) could have been spent doing something useful (grocery shopping, reorganizing a closet, untangling my spaniel’s matted hair), but instead I was browsing the asoiaf reddit, or something similarly unproductive. The gap between what I do and what the better part of me wants to be doing is palpable.

That gap exists for all of us, and often the instrument we choose to try to close it is motivation. Motivation is a precious currency in daily contemporary life. For so many of our problems, it seems to be the answer. Getting more motivation will be the key that unlocks cleaning out the garage, getting the dog groomed, finally getting on a good exercise routine, etc.[1] The people in our lives who seem highly motivated tend to be more successful, too (or at least more put together). A whole industry of books, apps, and podcasts promises to increase the consumer’s motivational reserves through knowledge, techniques, and paradigms — did you know people who make their beds every morning are 24% happier and have a 27% higher income?[2]

Given the centrality of motivation in our everyday lives, it’s natural for us to approach Christianity through the same lens. How do we get the motivation to go to church more, read our Bibles more, etc.? Last installment, we talked about how gratitude for God’s love — and for what God did for us in Jesus — gets enlisted as a motivational tool, and how that enlistment runs counter both to common sense and Paul’s letters. Other common motivational tools in Christianity include obligation (doing X is your duty), virtue formation (doing X will sanctify you), evangelism (doing X will make people notice there’s something different about you and possibly provide an opening to talk about faith), spiritual warfare (doing X will spite the devil or constrain his power), and so on.

The New Testament’s use of moral motivation in the context of moral exhortations coincides with some of those motivations and diverges from others. Perhaps surprisingly, Paul occasionally appeals to what we might call threats[3], the epistolary section of Revelation uses the language of rewards and punishments[4], and on one occasion Paul seems to appeal to a sense of competitiveness by comparing the Corinthians to another church.[5] Those types of appeals, though, are relatively rare.

The bulk of Paul’s exhortations could be sorted into roughly three groups: (1) bare exhortations without any motivational context appended to them (do X); (2) exhortations based on results (do X because it will result in Y); and (3) exhortations paired with new information.

For the first category, bare exhortations, it’s helpful to view the human will through an ancient, rather than modern, lens. For Aristotle, Augustine[6], Aquinas, and most of the Christian tradition until recently, human desire is always for some apparent good. Sin is disordered pursuit of the good, such as immoderate pursuit of a good (e.g. eating too much cake), preferring a lower good to a higher one (rewatching Game of Thrones instead of reading War and Peace), etc. Thus sloth is desiring and choosing the good of rest even when doing so prevents the attainment of higher goods; vengeance is choosing the lesser good of justice over that of love or the well-being of the other, etc. In all cases, the will isn’t drawn to doing evil for the sake of doing evil; rather, it is drawn to a good. A disordered will — and we all have disordered wills — is one that prefers lower things to higher: for example, my will often chooses eating tasty food over health.

For many actions, the good of the action is self-evident. For example, if it’s freezing and you tell your child to come sit by the fire, you don’t need any extra motivation or tricks; proximity to the hot fire is its own reward.

Likewise, for many of Paul’s moral imperatives, there are no external motivators presented. In such cases, the good itself is almost always readily apparent. For example, in Romans 12, Paul says, “let love be genuine … live peaceably with all.” He doesn’t wax eloquent about why peace is a good thing, or why we should want it — he simply implores them to do it. Paul provides no additional “motivation,” and it’s hard to imagine why he would. Rather, the apparent good of the act itself impels the will the same way the warm fire impels the child.[7]

Conspicuously absent from Paul’s exhortations is any attempt to change his audience’s desires. They may want to live peaceably with all, or they may not. The exhortation is addressed to the heart as it is. That is not to say Paul doesn’t anticipate change in his hearers. One can be built up by others (a theme of 1 Corinthians), one’s desires can be changed by the Holy Spirit (Phil 2:13), and suffering may produce hope (Rom 5:1–4). More radically, Paul’s hearers might be (passively) transformed (Rom 12:2)[8] and have become a new creation (2 Cor 5:17). The change happens, if it happens at all, in the hearers’ lives over the course of time. In the more theological sections of his letters, Paul acknowledges these mysterious dynamics of change of heart, but he does not try to personally harness them to induce his audience to follow his exhortations. The exhortations are presented separately from — and largely unconnected to — his thoughts about whether and how the heart might change.[9]

A wise youth minister used to tell us we had way more influence over each other than he did over us. The same is true in parenting, therapy, and a number of other circumstances. Changing someone’s heart — even a tiny bit — is long, messy, relational work. We long for the magic words to unlock a problem with someone else, but the problems run so much deeper than a sentence, a paradigm, or even anything that can be expressed in words. From that standpoint, of course Paul isn’t going to give advice — “live peaceably with all” — and then some magic fifteen-word formula that makes the pot stirrers lay down their spoons. The formula doesn’t exist, and change of heart doesn’t work that way. Paul’s lack of attempts to change his readers’ desires reflects a basic reality of human life: it’s extremely hard to change someone’s desires, and doubly so when you’re consciously trying to change them.

Similarly, change of heart is not brought about by oneself. Though the instruments may be other people, the Spirit, or suffering, “it is God who is at work in you, enabling you both to will and to work for his good pleasure” (Phil 2:13). As such, when Paul urges specific good works, he does not pair them with feeble attempts to incrementally change his hearers’ hearts to want to do them more. Instead, he addresses the heart as it is, the heart as the Spirit — working in that person’s life — has made it and will make it.

***

The remaining two categories of motivators paired with Pauline imperatives can be addressed quickly. The second, exhortations based on results, are actions are not necessarily good in themselves but that produce a good result.[10] For example, you might cook dinner not because you love cooking, but because a friend is sick and you want to take them dinner. In that case, an exhortation might look like, “(a) cook dinner for your sick friend, for (b) in doing so you make their day better.” You do (a) for the sake of (b). Many of Paul’s exhortations follow this pattern: “But if anyone has caused pain… This punishment by the majority is enough for such a person; so now (a) instead you should forgive and console him, so that (b) he may not be overwhelmed by excessive sorrow …” (2 Cor 2:5–8); “(a) Give no offence to Jews or to Greeks or to the church of God … so that (b) they may be saved” (1 Cor 10).

As in the first category, bare exhortation, the buck stops with the human will. If the will desires (b), then it works as a motive for doing (a); if not, it doesn’t. For most acts, the results may be different. For instance, one with a strong sense of justice may have no desire to prevent a wrongdoer from being overwhelmed by sorrow (as in 2 Cor 5), but the same person may feel a strong desire to evangelize others (1 Cor 10:32).

That points to another key aspect of Pauline moral motivation. We often see getting motivated as a sort of general gearing up of the will to address whatever tasks need doing; for Paul, by contrast, different acts result in different goods. There is little sense in Paul of motivation in general as some sort of personal resource or muscle.

The third category involves announcement of new information. To borrow from the Gospels, if you learn you will die tomorrow, you may not spend the day planning for retirement (see Luke 12:16–20). Similarly, in 1 Corinthians 7, Paul gives various bits of advice in light of the fact that “the present form of this world is passing away.” In 1 Corinthians 6, Paul tells his audience they should try civil cases in the church because “the saints will judge the world,” so they are perfectly competent to judge civil cases. While the new information may provide a reason or context for acting, again Paul does not himself try to produce the desire for good.

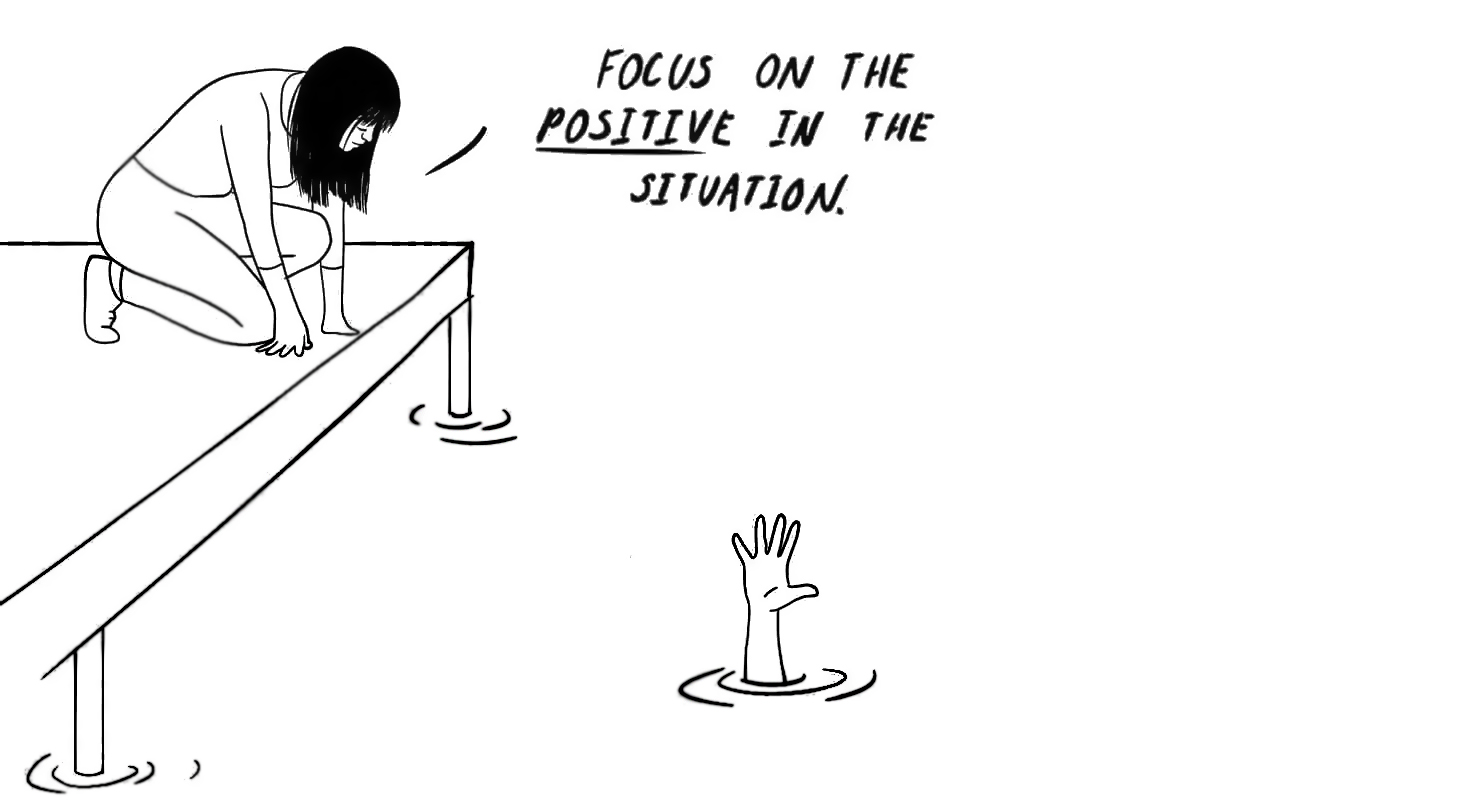

By contrast, in many contemporary Christian sermons and books, the object appears to be to somehow infuse righteousness, the desire for good, a good will, or a strong sense of motivation-in-general to the audience. In more intellectual churches this can look like a new paradigm for thinking about moral action; in more emotional churches it can look like an attempt to gin up pietistic feeling in oneself. Many of these paradigms harness dangerous and potentially destructive energies: for example, they may appeal to shame to motivate conduct, or they may appeal to pride (“Don’t you want to be the kind of person who does X?”).

Even apart from making common cause with destructive forces like shame or pride, these appeals can, ironically, destroy whatever virtue inheres in the action. If you bring a meal to a sick friend because you want to view yourself as the kind of person who takes meals to the sick, then the action is done for oneself, not the other. If you bring a meal to a sick friend because you’ve been guilt-tripped into doing it, then again you do it for yourself, not your friend. And if you bring a meal to a sick friend to cultivate your own virtue, then you do it again for yourself, not your friend.

The irony, then, is that doing a good act for any reason other than the good that inheres in the act (the first category) or naturally results from it (the second category) destroys the virtue of the act. This is one reason why religions that hold out salvation as a reward for one’s own good works cannot produce good works; if one brings a meal to a sick friend to earn heaven, then one again does the act for oneself, not the friend.

The radicality of Christianity is that the assurance of salvation by grace is the only thing that can free you to do good works entirely for their own sake. That ability to do good purely for the sake of the good done is a crucial dimension of Christian freedom.

The lack of motivational techniques in Paul’s exhortations, then, is not an oversight or a gap that needs filling by the eager preacher or writer, but an element of Christian freedom. The exhortation is put before us, and it can be done out of pure motives only by one fully assured of God’s grace. Grace alone frees one for genuinely moral action. That is one of the ways that grace alone, paradoxically, can truly fulfill the Law (see Mt 5:17).

Of course, that same grace creates the possibility of rejection, of not responding. And we are brought, again, face-to-face with that gap, familiar to Paul, between what we should do and what we actually do. But Paul resists the temptation to bridge that gap by motivational techniques. Instead, he recognizes the gap, dwells in it, confesses sin, and asks God for deliverance (Rom 7:14–25).[11]

Ultimately, the individual’s entire moral life becomes swallowed up in God’s justification of sinners, which is simultaneously the condition of freedom for moral action and secures our future on a basis wholly independent of our successes, failures, virtues, and shortcomings: “There is therefore now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus” (Rom 8:1).

This is so good, Will!