In eager anticipation of the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation (not to happen, incidentally, for another five years), we’re doing a short, slightly speculative series on a Reformational history of the English Reformation. It also doubles as a book review of Hilary Mantel’s fantastic, Booker-winning Wolf Hall, the source for a fair amount of the detail here:

In eager anticipation of the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation (not to happen, incidentally, for another five years), we’re doing a short, slightly speculative series on a Reformational history of the English Reformation. It also doubles as a book review of Hilary Mantel’s fantastic, Booker-winning Wolf Hall, the source for a fair amount of the detail here:

King Henry the VIII had earned the title “Defender of the Faith” for his jeremiads against the burgeoning Lutheran movement in central Europe. God-fearing in a quite literal way, it seems he valued theology highly, was constantly nervous about the threat of divine judgment, and was most deferential to his spiritual and political advisor, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. Henry was also a great leader and an astute statesman; under his early years, England became something of a tastemaker in the Western European power struggle, becoming an arbiter between Charles V’s Holy Roman Empire (at the time including Spain, perhaps the height of Hapsburg power) and the ever-powerful France, at the time enjoying the amity of both.

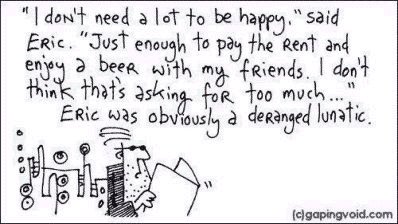

Henry, however, had a few besetting weaknesses – impulsiveness, appetite, and an insecurity only possible for a man expected to do great things. Though he had enjoyed several extramarital affairs, nothing short of divorce and remarriage could provide him with a legitimate son and heir. Women, of course, were to blame for not conceiving a son (we’re still in a very patriarchal culture), but nonetheless, one must imagine that Henry felt the weight of insecurity about it too. Though we want to assign blame to someone or something, emotions are always indeterminate, shifting, and partial – Katherine of Aragon’s fault, Henry’s own impotence, or the judgment of God?? One has to imagine that a mixture of guilt, extreme marital resentment, and inadequacy were all playing around, in now-uncertain proportions, in his heart. And we know, of course, that ‘what the heart desires, the will chooses, and the mind justifies.’ Defender of the Faith!? Not if the heart has something to say about it!

So although Cranmer and others eventually provided intellectual justification for the split, Henry’s original instinct to procure an annulment despite the Vatican’s disapproval provided the kick-off – we make our most important decisions under emotions and compulsions, not with clear reasoning and theological good-sense. So the theological elements were crystallized (in the chemical sense of the word – they were already dissolved, as it were, invisible in the intellectual miasma of the day) as ‘the mind’s justification’ for the ‘heart’s desire’ to allow ‘the will to choose [it]’.

So are the insights invalid because of the regal appetites and political pressures that allowed them to flourish? By no means! The beautiful thing about this less-than-ideal break is that the theology contains its own means of self-interpretation and critique. That is to say, sixteenth-century Roman Catholicism, as it was practiced, couldn’t account for Henry the Defender’s actions nearly as well as the later Thirty-Nine Articles could account for them. We act against our own ‘better’ judgment, we often cannot help but sin, and finally, God uses that sin to redound unto His glory. He specializes in using our missteps, our backcountry Nazarenes, our affairs with Bathsheba, etc, to bring about His purpose. And so, however appetite-driven and condemnable some of Henry’s judgments may have been, God works – and works beautifully – sub contrario, or under the guise of His opposite. Calvin emphasized that the truth about God can be read in the night sky (Rmn 1:20), but we’re on equally solid footing when we say that the truth about man can be read in history and experience (Rmn 7:15-21). The power of Reformational theology wasn’t that it makes people better so much as that it provides a better hermeneutic for understanding how limited and impulsive we are. It’s not paradoxical, nor even ironic that the men who rediscovered these insights also lived them in especially stark ways – indeed, it’s entirely fitting and, it appears, the more questionable parts of the Reformation’s history may have served it best.

COMMENTS

One response to “A Reformational History of the English Reformation, Part 1”

Leave a Reply

Be something of a history geek, I think it’s important to emphasize Wycliffe and Lollardy before the Tudors even took the throne. That and the burgeoning English nationalism that got the Plantagenets in trouble with the Pope. There was all sort of discontent towards Rome seething before Luther nailed the 95.

Funnily enough, what really blew the powder keg was the insatiable appetite of a king and the paranoia for a successor.

Yet, the English reformation, while presenting some good gospel truth in the 39, became a tool of the state and recreated the sort of christendom of Rome. Big successes and even bigger failures, yet the Kingdom comes still.

Cal