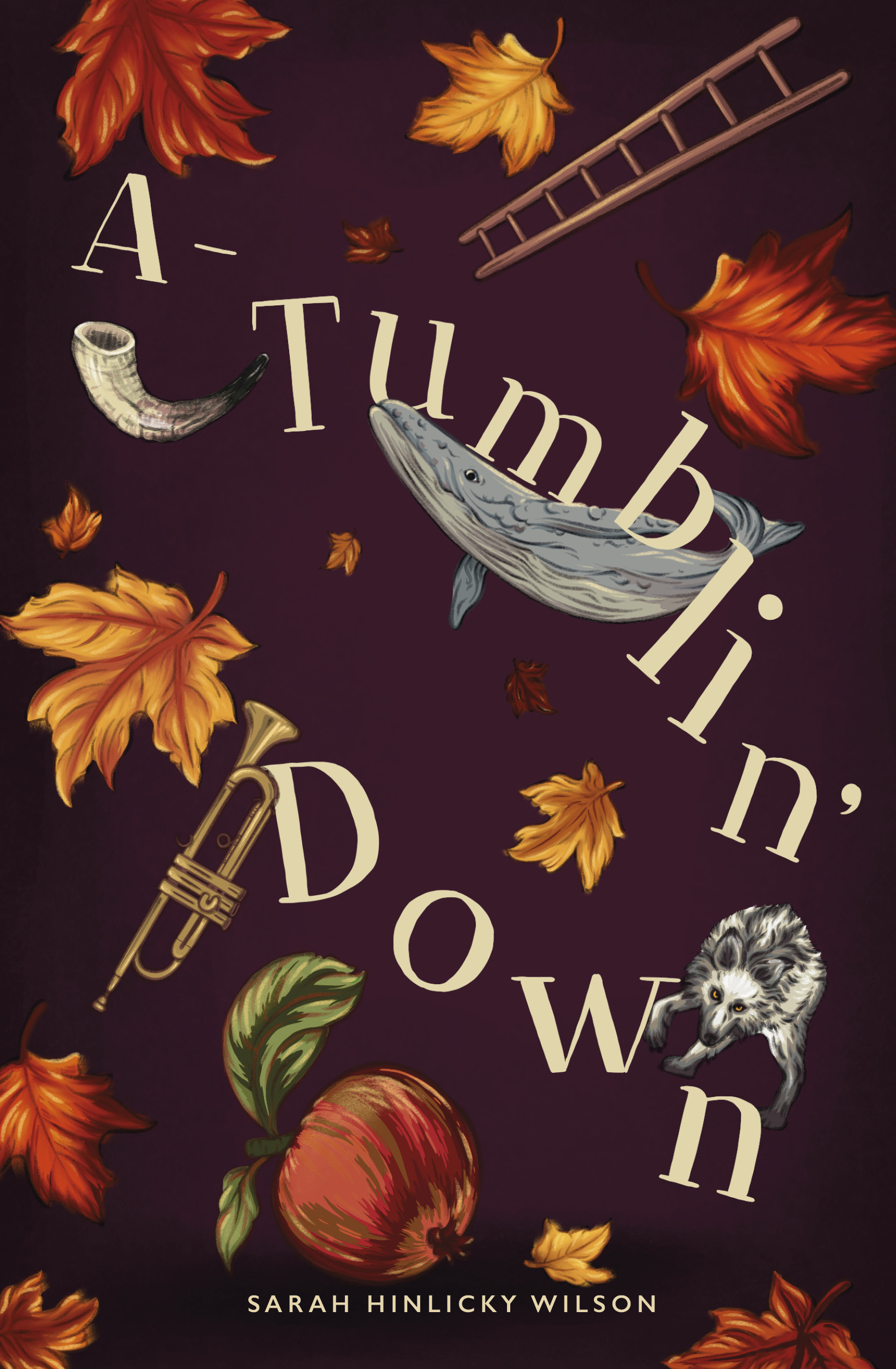

[Editor’s note: the following is the first of four excerpts from NYC Conference Speaker, Sarah Hinlicky Wilson, and her latest novel, A-Tumblin’ Down, the story of a Lutheran Pastor and his family, sudden tragedy, grief, and the grace needed to survive.]

Kitty lived in a parsonage with white wooden siding and big green shutters. A strip of gravel bordered by hydrangeas separated the house from the church, which was covered with the same white wooden siding but had no shutters at all; its splash of color was a pair of bright red doors out front. Church and parsonage alike perched at the top of a sharply twisting driveway on the south side of Shibboleth, New York, so high up over the town that Kitty called it their “eyrie,” savoring the strange word. On summer nights of slashing rain and violet-tinged lightning she declared it their “eerie eyrie,” savoring equally the homophone.

In the meadow behind the house grew a tangle of goldenrod, Queen Anne’s lace, and blue chicory. Kitty devoted hours of her waning summer vacation to attacking the milkweed that grew riotously throughout the tangle. “It reproduces like rabbits,” she would solemnly inform the teenage girls at church, with no clear notion of what that meant or why it made the girls conceal little smiles. Her weapon for the attack was a sturdy branch of sugar maple. She swung and sliced with the precision of a samurai. Every so often she stopped to split open a pod and let the milk trickle out, stroking the opalescent scales and soft fur, before renewing the attack.

Sometimes, when she was savaging the milkweed, or braiding corn silk the exact same color as her hair, or threading a daisy chain that would inevitably split and fall apart, her mother would stick her head out the pantry door and warn Kitty, for the thousandth time, to stay away from the east edge of meadow. Beyond the parsonage, past the lilac tree, where the curly dock with its rust-red smokestacks of flowers gave way to layers of shattered rock, there was an almost sheer drop to the saddle between the hills below. “You can’t see how dangerous it is,” Carmichael explained again and again, because the drop-off was obscured from sight by the blackberry canes gripping the rock face all the way down. “I don’t want Saul and Asher getting any ideas from seeing you over there.”

Kitty always replied irritably, “Yes, I know,” because she did know, though exactly how well she knew she never mentioned. Within a week of moving into the parsonage three summers before, when Kitty was still only eight, she’d found a low shallow cave just below the lilac and just above the drop-off. No one else in the family knew about it. Whenever she disappeared, they figured she was crawling inside the forsythia tunnel or hiding in the heart of the lilac tree. No one had any idea that in fact she shimmied into a dry mouth of rock to hold her council meetings.

Kitty thought her mom’s warning was silly anyway, because the really terrifying thing about their eyrie was not the drop-off but the driveway with its pair of hairpin turns and the sensation of gravel skidding beneath the tires even in hot dry weather. Driving it in winter was enough to make your heart stop, and even Asher didn’t complain about putting on his seatbelt for that. The founders of Mt. Moriah Lutheran Church must have chosen their site because the land was cheap. Its location certainly didn’t do it any favors through Shibboleth’s long snowy season. There are limits to what even feisty old German ladies will endure.

“You know, Pastor,” Mrs. Feuerlein would say in her gentle growl, “I vorked in zhe hospital laundry for sheventeen years, I escaped from zhe Stasi, I shlept in barns, I accepted rides from shtrangers, you know zhere is nozhing zhat I am afraid of, but I vill not drive up zhat driveway vhen it is icy.” Mrs. Kipfmueller would nod in solemn agreement, despite the fact that her ancestors had left Germany a century and a half earlier and tarried in Brazil for more than half that period before landing, improbably, in Olutakli County. Then Pastor Donald would assert that they were both remarkable women and surely never stayed away from church unless extreme circumstances required it.

And so at least once a year, when a snowstorm direct from the Great Lakes dumped its payload late on a Saturday night, nobody would come to church at all, because even if the county roads got cleared in time, the church’s driveway never did. Then on Sunday morning, Kitty and her little brothers and their mother would tromp across the pristine snow to sing as loudly as they could in the empty sanctuary, but they wouldn’t ever have communion. The first time it happened their mom said, “Can’t we?” and their dad, faintly shocked, said, “Carmichael, the sacraments are not a private family affair.” Kitty was surprised at how easily her mother accepted this, because as far as she could tell there was no boundary between church and family at all, especially considering where they lived. But then Kitty didn’t much like those pallid little wafers that gummed up on your tongue anyway, so it wasn’t that big a deal.

Access to a vacant church where you could sing yourself hoarse was one thing, but Kitty knew that the real goods came from the English department at the college where her mother worked, a promised land with treats far better than milk, honey, or communion wafers: an infinite supply of felt-tip pens in blue, black, red, and sometimes even a luscious brown, highlighters in lurid yellow and pale green, stacks of post-it notes in pastel colors, cute little black-and-white bottles clearly labeled “Liquid Paper” yet unfailingly referred to as “white-out,” and composition notebooks colored like cows.

“Did you bring me anything?” Kitty demanded one evening toward the end of milkweed season. She had obliged with a “Whee! Mommy!” and an enthusiastic kiss before settling down to business.

“No,” said Carmichael.

“Hmmph,” said Kitty.

“Sweetheart, the main job of an English professor is to read, not to collect office supplies. You should shift your focus a bit.”

“I read all the time,” she sassed. “I read more than all the kids in my class put together. They still think ‘Alice in Wonderland’ is a movie. I wanted some more post-its. What are we having for dinner?”

“Roasted post-its,” said Carmichael.

The phone rang. “Can I have a snack?” Kitty interposed before her mother took the receiver from its cradle.

“Run into the pantry and get an apple,” then, “Hello?”

Kitty did as she was told, bringing the peanut butter along for good measure.

“No, I can’t come down just now,” Carmichael was saying as she returned. A whispered “Bammy” was sufficient to explain.

Kitty heard the hiss of telephonic reproach.

“Mom, I don’t understand why I have to keep explaining this to you. I can’t just pop down for a weekend. Donald works on Sundays. I can’t leave him alone here with the kids.”

“I don’t need looking after,” said Kitty loudly.

“Plus my classes begin next week, and Asher is starting kindergarten the week after. There’s just too much going on right now.”

Carmichael’s silence witnessed to the objections at the other end of the line.

“Look, even if I could manage, the kids don’t want to miss Sunday School,” said Carmichael. A sudden warning note sounded in her voice out of all proportion to the words. Kitty checked to see if her mother’s teeth were clenched. She’d always wanted to see clenched teeth.

Apparently Kitty was not the only one to detect when a line had been crossed. Mollifying sounds murmured through the receiver. Carmichael’s hunched shoulders dropped an inch or two, almost back to their usual position. Then she said, “Why don’t you two come up here for Labor Day?” A pause. “All right, then come later in the month when the traffic won’t be so bad. We’re always here. Every weekend without fail.”

Platitudes crossed the wires and she hung up.

“Bammy and Bampy are coming up for a visit later next month,” Carmichael announced with a grand exhalation.

“I know. I heard,” said Kitty pertly. “Why we can’t go and see them? I like New York. I wouldn’t mind missing Sunday School for once. It’s boring.”

“I don’t want you to miss Sunday School, and I don’t like to leave your father alone on Sundays.” Carmichael picked up the apple and scrubbed it in the sink like it was Asher in the bathtub. Asher never let a day go by without ending it grubby.

“We never go to church when we visit them,” Kitty remarked. She noticed her mother’s shoulders rising again.

“No, we don’t,” said Carmichael. Her tone was so neutral that it was anything but neutral.

“They don’t believe in God, do they?” The thought occurred to Kitty for the first time, but she knew all at once with absolute certainty it was true. The knowledge was tantalizing and horrible.

“No, they don’t,” said Carmichael. The apple gleamed.

“They’re ay-thee-sists!” cried Kitty.

“Atheists,” corrected Carmichael. “But not really. ‘Agnostic’ is a better word for them. It’s not that they think God doesn’t exist. They just don’t care.”

Kitty crouched on the kitchen stool and dug into the peanut butter jar with a soupspoon. “Have they always been like that? Have they always been agnostic? Wait, does that mean you never went to church or Sunday School at all when you were a kid? What did you do on Sundays?” As she glommed peanut butter into her mouth, a whole new prospect opened up to Kitty: a world where Sunday mornings were every bit as free as Saturdays. It staggered the imagination, and Kitty was not deficient in that department.

Carmichael shrugged. She centered the apple cutter over the stem and pushed hard. The apple blossomed like a flower. “I just played, when I was little. Or watched TV. Bammy and Bampy read the paper. Sometimes we had people over for breakfast and I made pancakes or waffles for everyone. That was when I was a little older.”

“You knew other agnostic people?”

“Lots of ’em,” said Carmichael.

Kitty stopped to digest the revelation that her mother was a foreigner. A refugee from a strange and wondrous place. Horrible, yes. But wondrous all the same.

Carmichael chewed on a piece of apple and stared at nothing. “I could make Chicken Marbella for supper if there are any of the good green olives left,” she mused. “No, wait, that recipe needs to marinate overnight. I’ll just make something up.”

Kitty’s mind churned down another unimagined path, then burst out with the demand, “How come you believe in God?”

Carmichael pulled her arms out of the cupboard along with a package of prunes and a can of tomatoes. “Things make more sense to me this way,” she said. “God explains things. My mom and dad have spent their whole life explaining things one way or another, but I was always suspicious of their explanations. Like they were trying to cover up stuff that didn’t make sense to them. Or blocking out a whole big chunk of reality that they didn’t want to admit was there. I didn’t know any of that when I was little, of course. We never talked about it directly. I had to grow up and find out. Meeting your dad helped.”

“Did you believe in God when you and Daddy met?”

“Not by name, but I think I did in my heart. Your daddy told me who God was, and then it was easy.” A cutting board emerged, then a knife. Carmichael sharpened it on the steel.

“Do you love God?” Kitty pressed.

“You are just like I was, when I was a little girl,” said Carmichael, beeping Kitty on the nose. “Always asking the hardest questions.”

Kitty said nothing. She was trying to decide whether she liked being called a little girl. At least it was better than being accused of growing up and becoming such a fine young lady.

“Yes, I love God very much,” Carmichael said at last.

“Me too,” said Kitty. She shoveled another load of peanut butter into her mouth and slurped it around while Carmichael settled the cast iron skillet on the stove.

Kitty loved God because she had always loved God, as long as she could remember being alive. It didn’t feel like much, to be honest. Not like loving her parents or her brothers or the council. But it was a solid sort of thing that was always there.

Suppose it wasn’t there, though? That’s what it was like for her own mom as a kid. Could you really start to love God when you were already an adult, and already a liar? Kitty knew one thing for sure about adults, and that was their rampant tendency to lie, especially for good causes.

What about Bammy and Bampy? They were adults, but nice ones. Kitty didn’t think they were liars. But weren’t they lying when they said there was no God?

She’d have to take the question to the council. They’d know better than she did. It was too late to visit anymore tonight, but she could talk with them about it tomorrow.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply