Standing in front of the American Psychological Association (APA) in 1961, New Testament scholar Krister Stendahl delivered what would become one of the most influential essays in the twentieth century: “The Apostle Paul and the Introspective Conscious of the West.”

To this room full of psychologists specializing in the alleviation of troubled consciences, Stendahl argued that the apostle Paul never suffered from any such malady. Paul did not have a trouble conscience, but a “robust” one, with little introspective awareness of his own sin and guilt. Stendahl believed that we mustn’t, as reformer Martin Luther did, ask 16th century questions of 1st century texts. Paul did not have a conversion experience, moving from guilt to relief through disruptive divine intervention. Paul’s religious experience was instead more cumulative, akin to the calling of the prophets in Hebrew scripture, gaining new insights that build upon Paul’s prior convictions.[1] Paul the Jew was simply called by God to be the apostle to the Gentiles. Paul did not announce divine relief to those burdened by guilt, but the advent of the Messiah.

Having unearthed the supposedly original meaning of Paul, Stendahl calls for a new era in church life, in which the question of guilt is pushed aside and evangelism has (at most) a subsidiary function.[2] Like Paul, one need not ever feel the pangs of guilt in order to become a Christian. Stendahl argues that the entire paradigm of guilt and grace, of sin and forgiveness — so central to both Catholic and Protestant theology — has no basis in the writings of Paul.

It would be difficult to understate the sweeping implications of Stendahl’s argument and its broader impact.[3] Stendahl aims his rhetorical sledgehammer at not simply modern interpreters of Paul, but the entirety of Western thinking: from Augustine and Luther right up to Sigmund Freud, the “secular climax” of the introspective conscience. An entire tradition of thought spanning well over a thousand years — all of which, Stendahl argues, depends upon a misunderstanding of Paul. Addressing not just historians and theologians, but average reader of the Bible and psychologists, Stendahl seeks to refashion Western society by liberating it from an introspective Paul who never existed.[4]

Though Stendahl posited himself as a disinterested historian, he nevertheless provides a historical-religious argument that paralleled contemporary developments in the field of psychology. He cites a panel discussion at the APA in the previous year, where psychologist Albert Ellis, an early pioneer of the now ubiquitous cognitive-behavioral therapy, contended that “no human being should ever be blamed for anything he does; and it is the therapist’s main and most important function to help rid his patients of every possible vestige of their blaming themselves, others, or fate and the universe.”[5] To Ellis, labeling people as sinners hampers their ability to address their problems. There are no sinners, only those who suffer from poor mental health. One does not need a priest, but a therapist.

As frequently as Stendahl criticizes Western thought for “modernizing” the Apostle Paul “for apologetic, doctrinal, or psychological purposes” (p. 214), Stendahl somehow fails to recognize that he is asking 20th century questions of 1st century texts. If psychology was moving beyond notions of sin and guilt, Stendahl was more than happy to provide them an apostle to the Gentiles who showed no signs of a troubled conscience — a Paul liberated from the restrictive confines of repressive notions of guilt — and, by extension, a church that keeps up with the changing times. These apologetic concerns color the argument so thoroughly that Stendahl’s analysis is skewed as a result.

Stendahl searches Paul’s letters for explicit signs of a troubled conscience and, finding none, declares the case closed. The remainder of the article attempts to answer objections to his thesis. But the absence of evidence is not evidence of an absence. Paul’s letters were always written to address specific pastoral questions and controversies that arose from their recipients. He rarely spoke in much detail about himself and he certainly does not provide precise autobiographical information, let alone a first-person narration of the state of his conscience on his journey up the Damascus Road. Indeed, were it not for the Book of Acts, we wouldn’t know where Paul even was when God “revealed his Son to me” (Gal 1:16). Consequently, insight into the mind of Paul at this time must be inferred from what he writes.

Even given the slender data available, there is ample reason to suspect that Paul’s conscience was far from untroubled. As Paul described in Galatians 1, his life story consists in a two-act drama. There is a Before Christ and an After Christ. Before was Paul’s “former life in Judaism,” during which he was a violent persecutor who tried to destroy the church. The turning point in this two-act drama is the revelation of Jesus and his call to become an apostle to the Gentiles. In Philippians 3, Paul describes the same story, but in more vivid detail, accounting for what Paul had, what he lost, and what he gained. Before Christ, Paul considered himself to be an exemplary Jew: duly circumcised, blameless in the law, and a zealous persecutor of the church. After Christ, there is immeasurable loss of everything, outstripped by what is gained. His prior righteousness according to the Law counts for nothing, having gained a righteousness from God on account of faith in Christ. After Christ, Paul’s life is marked by the sufferings of Jesus and the power of his resurrection. Though commonly called Paul’s conversion to become a follower of Jesus, we might today say that he deconverted from his earlier beliefs. [6]

If we were to inquire into the state of Paul’s conscience throughout this process, it is implausible he felt no guilt whatsoever. Paul was actively hostile toward the very person who sought him out. On the Damascus Road, Paul simultaneously encountered judgment and grace, producing in Paul not just a radical change of mind, but the corresponding feelings of guilt, remorse, and relief. While Stendahl contended that Paul’s letters demonstrate a “conspicuous absence of references to an actual consciousness of being a sinner” (p. 210), Paul’s ongoing characterizations of his former life suggest otherwise. Paul does not mildly recount, for example, that he strove to purge Judaism of blasphemy or that he judged Christians to be blasphemers. No, he was a violent persecutor of the church and therefore the least, most unworthy apostle (1 Cor 15:9). Even decades later, so far as Paul was concerned, he had not sufficiently “made up for this past terrible Sin” (Stendahl, p. 209) and his failure continued to prick his conscience.

Paul’s account of his conversion is therefore less a ‘calling’ and more “a story about the reversal of an enemy.”[7] Seen from this angle, Paul’s later claim of Law-abiding blamelessness carries a deeply ironic tone — his very blamelessness according to the Law condoned, if not encouraged, the killing of Christians. This autobiographical irony, that his own observance of the Law brought death, would undoubtedly come to inform his view of the Law and spur a dramatic rereading of his Jewish scriptures (most acutely seen in Romans 7). However holy the Law is, it is unable to provide the life it promises, Christian or not. Like many deconversion stories today, Paul’s Damascus Road experience left him questioning how it all went so wrong and what can be retained from the fallout.

However extraordinary the circumstances of Paul’s own conversion experience might have been, it formed a template for how he thought others came to faith – a template that was confirmed through Paul’s pastoral practice. Regardless of whether one was a Jew or Gentile, the story of one’s life is a two-act drama of deconversion and conversion, loss and gain, with Christ as the decisive turning point. Just as God called Paul by grace (Gal 1:15), so too did God call the Galatian church by grace (1:6). This pattern can be found in the church of Thessalonica, a sinful people who were similarly called by God (1 Thes 1:4) and thereby saved from the coming wrath (1:10). Or as Paul would write in his letter to the Romans, the God of Abraham only justifies the ungodly (5:4). Moving from guilt to grace, judgment to forgiveness, death to life, Paul experienced firsthand what would become the dominate theme of his ministry.

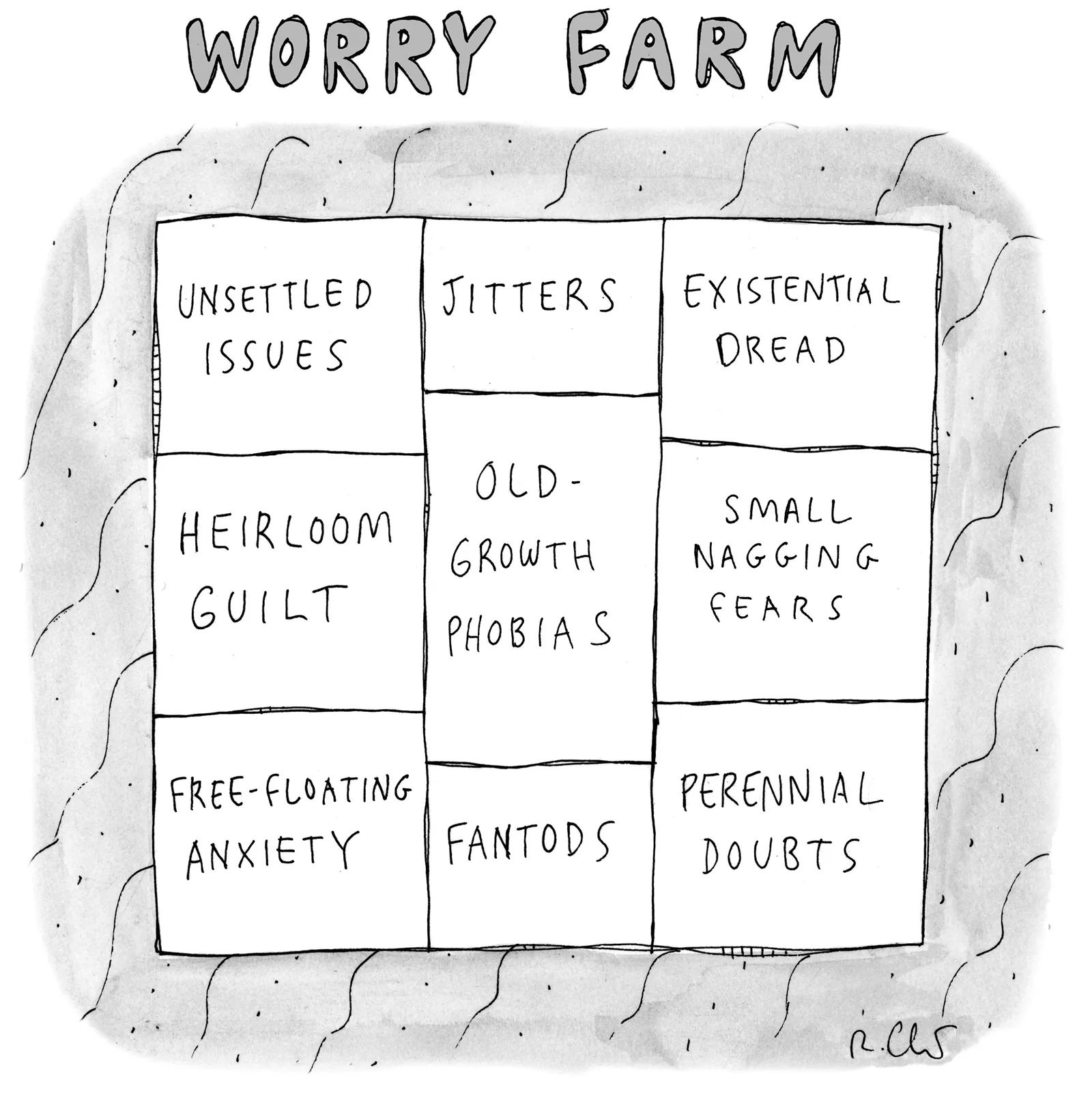

While Biblical scholars may have deemed Stendahl’s essay to be provocative and courageous, everyone else was simply happy to have religious justification for where they were already headed. Stendahl’s essay heralded a time when the traditional moral strictures of the church and society at large were loosened. The question of right and wrong became one of what was helpful or harmful, of self-care, wellness, and health habits. Or, in Stendahl’s later words, “Sin is sickness, not primary guilt.” Those who insisted upon retaining the old religion of guilt, judgment, and grace were viewed as regressive, if not dangerous. Even sixty-plus years later, the legacy of this shift remains, particularly within the realm of personal conduct. But the yoke of sin cannot be loosed by mere fiat. As much as the troubled conscience has been stricken from our lexicon, the problems of anxiety, stress, and guilt remain unchecked. Far from having nothing to say to our 21st century lives, Paul was well acquainted with the pangs of a conscience stricken by sin.

This is excellent, Todd! It’s always amazed me that people actually believe that humanity moved beyond guilt/anxiety in the 20th century. Have they never talked to anyone?

“[E]veryone else was simply happy to have religious justification for where they were already headed.”

This is so much our contemporary malady in the church, still. Nothing new under the sun!

Spot on, Todd! So true. What you said in footnote #3 also very true. Stendahl anticipated so much of the Pauline debate of the twentieth century.

Absurd that Stendahl finds no evidence of Paul’s troubled conscience in Romans 7…”For I know that good itself does not dwell in me, that is, in my sinful nature. For I have the desire to do what is good, but I cannot carry it out. 19 For I do not do the good I want to do, but the evil I do not want to do—this I keep on doing.”