Christ Carrying the Cross (1510-1535) by a follower of Hieronymus Bosch: I love the Northern Renaissance precisely for weird, often grotesque paintings like this one. It definitely stands in stark contrast with the art of the Italian Renaissance. Of course, someone might interpret these gruesome faces as antisemitic, but really it’s low anthropology. The artist is just depicting us human beings in our many shades of awfulness. Were you there when they crucified my Lord? Yeah, we were there, jeering him all the way. — Ben Self

The Ascension of Christ (1513) by Hans Süss von Kulmbach: Around the 1100s, one rather whimsical monk decided to illustrate the Ascension by featuring only the feet of Jesus, as the rest of his rising body had already left the frame. The theme features bewildered disciples (and sometimes the BVM) looking heavenward as the resurrected Jesus exits “stage up,” his wounded but restored feet our only visual into the surreal experience. Well-done expressions of this theme draw the viewer’s eyes upward in the same manner, a reminder that Jesus sits at the Father’s right hand and remains in control of all things. Kulmbach, the painter of this version, offers us a Reformation-era take on the event, adding perspective and detail its medieval counterparts lack. It’s (barely!) one of my favorite artistic depictions of my God, who himself has a sense of humor. — Bryan Jarrell

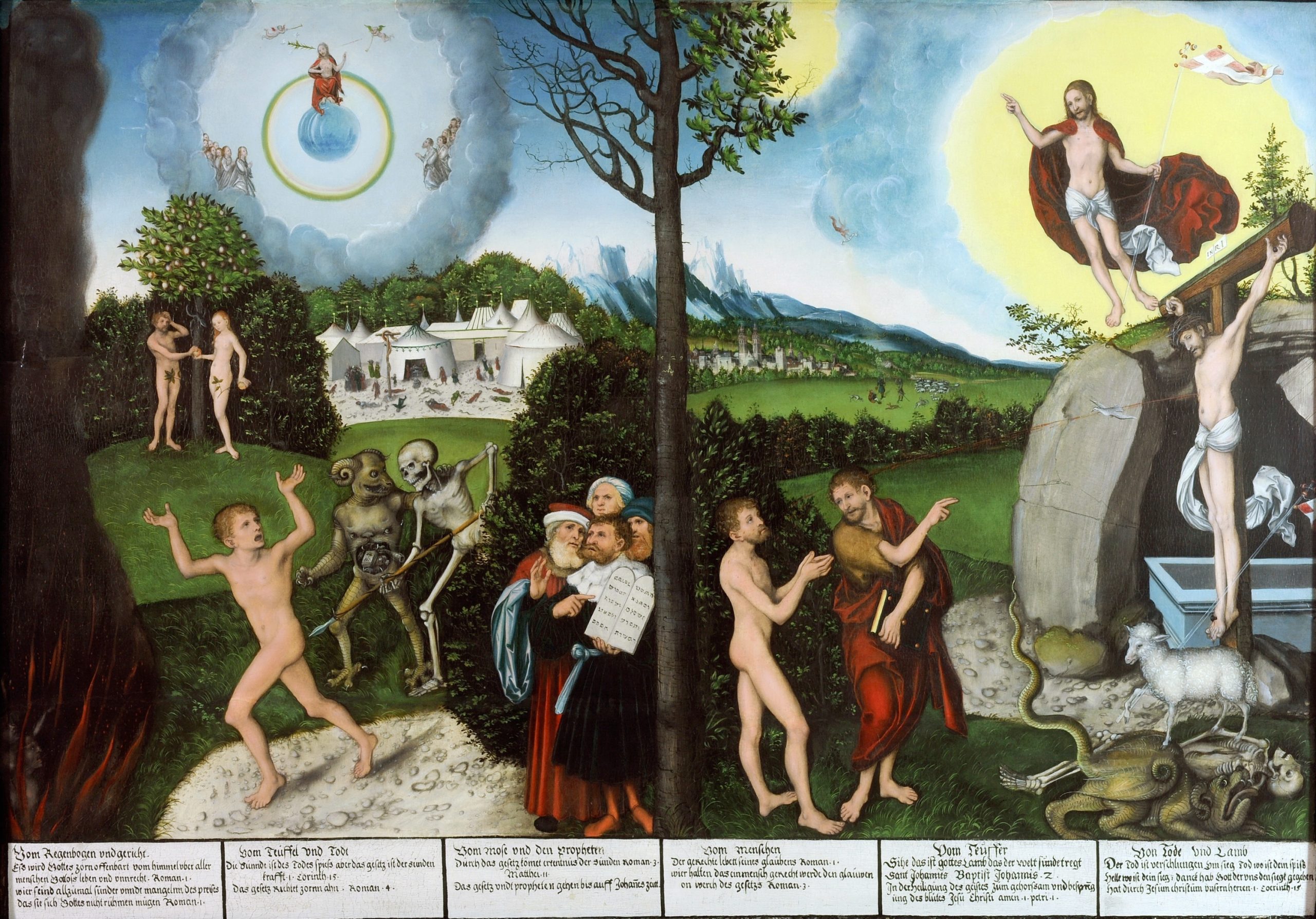

Law and Gospel (1529) by Lucas Cranach the Elder: If you’ve ever seen the “I saw that” sticker or imagined God glaring at you with disapproval, you’ve encountered half of Lucas Cranach’s painting “Law and Gospel.” The left side depicts a distant Jesus in the clouds, overseeing a world burdened by the knowledge of good and evil yet failing to carry it out. The central figure, exposed and distressed, focuses on the written law, driven by sin and death toward a fiery end. In contrast, the right side offers a vision of life under the tree of life: The central figure, still exposed, is unafraid and receptive to the teachings of the cross. Here, Jesus is near, triumphantly subduing the menacing creatures from the left and applying a thin line of his own blood to renew all things. — Davis Johnson

The Last Supper (1592-94) by Jacopo Tintoretto: I’m fixated by the angels in this painting. We see them spilling out through the hole the light of Heaven created, filling the air in an already crowded upper room. Every square foot is full of people and energy, physical and psychic; even the dogs and cats are busy! Yet, the angels aren’t distracted, their eyes are fixed on the figure of Christ — doing aerial backflips if necessary — not wanting to miss a moment of each event leading up to The Moment of Moments. — Joshua Retterer

The Calling of Saint Matthew (1599-1600) by Caravaggio: In this painting, Christ bursts into the room where (the soon-to-be Saint) Matthew and his fellow dandies pour over their sums. The glory of this masterpiece lies in the details: Light floods in from behind Christ. Is it an open door, or is another, eternal, light trailing Christ? Cribbing another Michelangelo, Christ’s hand intentionally mimics God’s hand in the Creation of Adam at the Sistine Chapel. But the best detail is the surprised look of the elder Matthew himself. — Ryan Cosgrove

Deposition (1600-1604) by Caravaggio: In 2017, I went on a quest to see as many Caravaggio paintings as I could find in Rome. I remember standing in front of this giant canvas (ca. 1600) in the Pinacoteca, part of the Vatican Museum complex, stunned by the emotion it evoked in me. Caravaggio, who broke the rules by using what we’d call folks off the street as models, depicts the disciple John and the Pharisee Nicodemus lowering the crucified Christ’s body into the tomb. Behind them are the three women (l-r, Mary the mother of Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and Mary of Cleophas) each with a different expression of grief. The slab on which they stand is the tomb’s cover, a horizontal echo of the cover of the ark of the covenant, making the grave into the Holy of Holies. Two details about Jesus are important. First, the white graveclothes are a foreshadowing of Easter. Second (and more important), whether he intended it or not, Caravaggio preaches of our Lord’s regard for sinners: On the side of the living, Jesus’ hand is closed, but on the side of the dead (and the dying, the sinful, and the godless) even in death Christ reaches out with an open hand. — Ken Jones

Saint Peter and Saint Paul (1616) by Jusepe de Ribera: This one hangs in my office. It’s Peter with the keys to Heaven, and Paul with the sword of martyrdom, but I can’t help but think of John when I look at it. In the center of the painting is yet another portrait. “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” It’s a portrait of “the Word became flesh…” — Joshua Retterer

The Descent from the Cross (1634) by Rembrandt: I first saw this painting several years ago at a Rembrandt exhibit at a local art museum. Aside from its striking use of color, it felt unique to me that instead of the more common “in process” crucifixion scene, he captures Jesus as a dead man, being lowered off the cross. The humbling descent of God moves me, for — as Scripture so often asks us — who can ascend to him? Relatedly, I love the imagery that although no one assists him in the work of salvation — for he does so single-handedly — now after his death he’s drawing all men from the darkness unto himself (John 12:32). — Christopher Wachter

Head of Christ (1645-1650) by Rembrandt: Of the dozen or so “Heads of Christ” attributed to Rembrandt van Rijn (d. 1669), only the one now hanging at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin is known to be from the great painter himself. Rembrandt may have used a Jewish model in an effort to depict Jesus more realistically. Rembrandt’s Christ is not in the midst of performing miracles or saving the world; this is not Good Friday or Easter Sunday, but more of a Random Tuesday. He inhabits (and thereby redeems) the quiet, perhaps even weary, moments that make up so much of our own lives. – David Clay

I’ve been doing a bit of noodling lately on Jean-François Millet’s The Sower (1850), of which he painted several versions. I’m doubtful he meant it to be Jesus, but I imagine Jesus when I look at it. This hefty, confident peasant farmer hurling seeds has become my mental stand-in for the central figure in Jesus’ keystone parable (Mark 4:1-20). Jesus’ parabolic farmer, who “sows the word” (v. 14), is a self-portrait. Everywhere Jesus goes in the Gospels, he scatters grace — small, self-contained promises of life and generosity, hope and resurrection. And his promises travel everywhere! – Larry Parsley

Christ Asleep during the Tempest (1853) by Eugène Delacroix: There’s something that’s always been comical about Jesus snoozing while the disciples panic. The painting encapsulates life fairly accurately — we freak out and lose our minds (sometimes even our paddles) as the waves of the day-to-day struggle seem to spell our demise. Meanwhile, Jesus catches Z’s knowing all will be well, not only because the wind and waves will be quelled with his own utterance but because he had perfect faith in his father. The painting feels like an offer to join him in that faith and perhaps enjoy a little rest myself. — Blake Nail

The Sermon of the Beatitudes (1886-96) by James Tissot: This small watercolor is one of hundreds Tissot painted after having traveled to Palestine in 1886. At a time when Bible scholars stripped their histories of Jesus of any and all divine aspects, Tissot took a different tact. He sought to depict historical accuracy with a “fidelity [to] the divine personality of Jesus.” The result is some of the most ambitious and faithful representations of Jesus in the last 150 years. This particular painting perfectly distills Tissot’s twofold aims, the novelty of Jesus revealed through quotidian history. Jesus is surrounded by crowds dressed in ancient attire and by a realistic Galilean landscape. The dynamic figure at the top inspires awe from the multitude and derision from a few. Jesus is recognizably a preacher, but somehow more than just a preacher. His face shrouded, this Jesus is mysterious and other-worldly. He might be speaking in the language of the people, but he does so with an authority greater than mere mortals. — Todd Brewer

Peter and John Running to the Tomb (1898) by Eugène Burnand: I don’t know if this counts, but it’s my favorite Easter painting: John and Peter on the way to the empty tomb. I think it expresses hope against hope better than anything I’ve ever seen. — Sarah Wilson

A great number of the paintings of Jesus that I’ve seen are off-putting to me, though Frederick Buechner managed to do an entire book on The Faces of Christ and many of the ones he selected were less schlocky than most. Two that speak to me are: Georges Rouault’s Head of Christ (1905), which communicates Christ’s pain, even fragmentation, in the face of this disordered world. And then Rembrandt’s Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee (1633), which tells the Gospel story and makes me think — given Rembrandt’s stunningly stormy sea — that Jesus must have been a pretty good sleeper. Imagine going from that tempest to what Mark describes as the “dead quiet” of the wind and waves following Christ’s command. Imagine it? I’ve experienced it. Which is more frightening: the storm or the dead calm? — Anthony Robinson

White Crucifixion (1938) by Marc Chagall: Occasionally, the best Christian art is actually made by non-Christians (see: “O Holy Night”). In this case, the artist is of course the great Jewish modernist painter Marc Chagall, who painted this version of the crucifixion while living in France on the cusp of WWII. (The crucifixion actually became a regular motif in his art, no doubt an image that personified for him the ongoing persecution of his people.) Why does this crucifixion speak to me so much? Well it feels like what Christ does in every generation: In this world of so much chaos, terror, suffering, and injustice, Christ stands up on a cross in the middle of it all, reconciling us to God with open arms. — Ben Self

Wales Window for Alabama (1963-65) by John Petts: I remember first seeing Petts’ stained-glass portrait of Jesus on the cover of Fleming Rutledge’s The Crucifixion. Like the book itself, the image reshaped and reinvigorated my understanding of the Cross. The story of its creation is profound. On September 15, 1963, four little black girls were killed in their church by a Ku Klux Klan bomb in downtown Birmingham, Alabama. The next morning, four-thousand miles away, Petts read about the terrible event in the Welsh newspaper and quickly offered to create and install a replacement window. The image itself is striking. A brown-skinned Jesus is in the cruciform position, his hanging head expressing not only anguish, but deep sorrow. According to Petts, Jesus’ right hand is turned against the powers of hell as well as injustice, hatred and sin, while the left hand is embracing all of creation and offering the forgiveness of sins. On this portrait, Rutledge writes, “His boots are blackened as if he has been marching in the mud, but his body appears transfigured in white light. The composition conveys utter helplessness and victimization, yet in the same image we seem to see a dimension of power and transcendence.” It is a constant reminder that God is no stranger to suffering and that he has taken the weight of our sin on his shoulders. — Sam Bush

Supper at Emmaus (1971) by Ivo Dulčić: When Mockingbird asked about my favorite painting of Jesus, I was initially a bit stumped. I like a lot of the usual suspects, like these paintings by William Holman Hunt, Dali, Gauguin, and Chagall. But I wanted to dig deeper, so I decided to look through an art book from college called The Faces of Jesus (text by Frederick Buechner). For some reason, I generally found myself more drawn to the sculptures than the paintings, maybe something about the three-dimensional physicality of them felt more appropriate for the Word Incarnate. However, this painting by Croatian painter Ivo Dulčić is one that I didn’t remember seeing before and that stood out to me. I’m drawn to the mystery of it. Jesus’ face is kind of obscured, and there’s a “great sunflower of light” (Buechner) blossoming behind him, with deep purples, blues, and fauvistic reds beyond that. It feels very 1971 to me, in the best way possible, and it makes me pause and really look at it, taking all the details in, while keeping Christ right at the center. — Joey Goodall

Jesus Laughing (1973/1976) drawn by Willis Wheatley and screen printed by Ralph Kozak: Sometimes we take Jesus, church, and ourselves more seriously than we should. I know I do. But it is not for serious business that Christ set us free — it is for freedom. When I find myself turning this freedom into bondage, or just plain overwhelmed by the weight of it all, I take a glance at this picture. Jesus is not teaching, not healing, not conversing, not navy-SEAL training his disciples so they might change the Greco-Roman world forever. All we see is Jesus’ face shining with the light of deep laughter. Maybe Peter just told him a joke. Maybe he just played a practical joke on Judas. Maybe the Galilean rumor-mill just stirred up some hot gossip. This piece of art is as unpretentious as it gets. It reminds me that laughter is a theological category, for since we laugh before we sin, shall we not carry laughter and jokes with us into eternity? Jesus wept, but he laughed just as hard. — Joshua Gritter

Jesus and the Lamb (1982) by Katherine Brown: My mom gave me this drawing on a card when I was young. Growing up, so much of my understanding about God, and Jesus, was about how I should respond to him, what I should be doing, etc. It all left me feeling like I was constantly being evaluated by God as to how “well” I was doing at being his child. This image, though, counteracted the behavior-management form of Christianity that surrounded me and offered me a glimpse of the freedom and love I’d eventually find in Jesus. It took a couple of decades for me to really begin to grasp what his grace means to me, but this image conveys a lot of that understanding: the reckless and deep love he has for me, the scars he still bears on my behalf, and the rest I find in him when I completely abandon myself to his love. It’s not super deep or artsy, but I find it beautiful. – Stephanie Phillips

Love Power Jesus (1997) by Jason Prigge: My favorite Jesus painting is iconic to the West Bank of Minneapolis (near the U of M) and is colloquially known as Love Power Jesus. Thousands of Minnesotans meet Jesus’ eyes daily as he stares down the traffic with promises of music, miracles, and ministries. What’s not to love? As I passed LP Jesus on my anxious way to seminary or my social work program, it reminded me that love is real power, not weakness, and that my “not enoughness” was accepted and loved. — Marilu Thomas

The Road to Emmaus (1997) by He Qi: The Gospels give us four uniquely beautiful resurrection windows to look through. Matthew sends us. Mark jars us with wonder. John gives us a glimpse of what Peter could become. But only Luke opens our eyes. He Qi’s depiction of Luke’s distinctive Emmaus narrative is vibrant with color and tender with feeling. One grieving disciple looks longingly into Jesus’ eyes, fixated on his every word. The other looks toward the setting sun. Unlike most contemporary Jesus art, He Qi does not zoom in on Jesus’ face. What we see instead are Jesus’ disproportionately large hands. Hands that hold two lost and grief-befuddled pilgrims. Hands big enough to hold the burdens we carry. And there in full bloom just beneath Jesus’ feet are three white flowers, a playful reminder that the garden that once was has blossomed again. — Joshua Gritter

The Hand of God (2000s-2010s?) by Yongsung Kim: I love the perspective of this painting. We see Jesus from Peter’s point of view when he is sinking in the water, after his step of faith onto the water and subsequent fear as he noticed the waves around him. The Bible says that Jesus immediately reached out his hand to save him. This painting portrays Jesus with a smile, which I love because it shows that he is not mad at us when we are afraid but is always quick to reach to where we are. — Juliette Alvey

Crucifixion (2008) by Craigie Aitchison: I love this painting for it’s starkness. I am a woman of vast emotions who lives in a world with vast complexities. Sometimes it feels like my own nervous system lights on fire in a matter of seconds. But when I look at this painting, Christ’s atonement becomes a bone-deep reality again for me. Cutting straight to the heart beneath the skin of our emotions and our own blindness lies the Son of God blazing with sacrificial love. — Janell Downing

Christ: The Mother Hen (2022) by Kelly Latimore: As a mom, I recognize this desire to gather my children to me and protect them as best I can (from Christ’s own words in Matthew), but I recognize that in reality, I am one of these baby chicks, helpless and needing the shelter and cover of my mother hens arms. — Jane Grizzle

Lamentations 3 (2022) by Janell Downing: Inspired by Soong-Chan Rah’s quote from his book, Prophetic Lament: “The church became the living acrostic in the sea of chaos,” and the Hebrew poetic structure of Lamentations 3: an intensified acrostic poem that holds in its entirety grief, suffering, confession, and hope, I created a contemplative double exposure back in 2022 during the riots in my city. Overlaying Michelangelo’s Pieta within a marshland in downtown Portland became a prayer that I return to often. Even in seemingly opposing narratives, lies at the epicenter, the hope of Christ in whom we are not consumed. — Janell Downing

The Prodigal Father (2023?) by a friend of my pastor: “The Prodigal Son” always seemed like a misnomer to me for a story about a prodigally loving father, who in this painting looks to me like a pretty good stand-in for Jesus. For all the squandering of the son in the parable, the father’s lavish love outdid it tenfold. That’s why I love this painting, which hangs on the wall of my pastor’s office. In our Christian faith, the most radical act is not us cleaning up and dragging ourselves back home; it’s the Father running toward us in our filth and mess. Whenever I see it, I am reminded that goodness and mercy run after me. — Kate Wartak

What a great list and post! So much to meditate on in these recommendations. Thanks!

Thank you for this rich, beautiful compilation. I am going to spend a long time with these paintings and comments.

Thank you for this list!

Ivan Kramskoi’s “Christ in the Wilderness” (1872) always unlocks something inside me:

https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/christ-in-the-wilderness/uwEOJTS-uQb5ww

Such a profound and human work.

Modern icon artist Kelly Latimore’s Tent City Nativity: https://kellylatimoreicons.com/blogs/news/tent-city-nativity

Good content bought out of the archives of time! So many paintings. Art begets art so keep it coming.

[…] rationale for our own ongoing “favorites” series: check out our other recent lists of films, paintings, and podcasts. This month, while we would not presume to quibble with The New York Times — which […]

[…] we continue to roll through our series of lighthearted lists (grace-in-practice movies, paintings of Jesus, podcasts, and 21st-century novels) we figured it was time to do a Bible-themed poll. We hope you […]

[…] Favorite Grace-In-Practice Movies (See also our Jesus Paintings and 21st Century Literature […]