All week the forecast was bad. Weather.com showed only thunderclouds, rain, and a long series of yellow lightning bolts. But when the day came — a day when college-aged Christians would gather outside to protest human trafficking — the storms held off. The clouds came in, but the air was clear. One of my friends, an Evangelical, laughed: “God said to the rain, ‘Not today!’” She waved her hand as if pushing away the unwanted, as if that were how the weather worked. Her confidence left me quietly stunned. What was on the one hand a slightly humorous remark was also a major presumption: God would manipulate the forecast for our little event while storms ravaged elsewhere. This was the same month a typhoon killed 6,300 people in the Philippines.

To speak so easily of God’s view of things can be, at the very least, alienating to those with less religious confidence. The literary critic James Wood recently described this tension in an essay at the New Yorker. Believers, he writes, can feel so close to God that they are expecting divine intervention constantly. Needless to say, the effect is suspicious:

Elaine prays for guidance about whether to take a roommate or move to a new apartment. Kate gets angry with God and “yells at him when things go wrong — when she organizes a trip for the church and the bus company is flaky or it rains.” Stacy prays for a good haircut, and Hannah asks God about whom to date, and sometimes feels he is pranking her in little ways: “I’ll trip and fall, and I’ll be like, Thanks, God.” Rachel asks for help with how to dress: “Like, God, what should I wear? … I think God cares about really, really little things in my life.”

On the one hand, such intimacy with God can seem bold, even stabilizing, especially when you are twenty years old and life is full of uncertainty. You’re not totally sure whether you’re good enough for that prospective job, or whether Ann likes the way you look as much as you like the way she looks, or whether you will pass your final exams. Or maybe you are middle-aged, and going through a separation, or have recently lost a job, or your family is mad at you. Within many destabilizing circumstances it is a relief to feel that the activity of God in your life might be the most obvious thing in the world. It is also brazenly malleable. God seems to be on whatever side you’re on, or gently pushing you in the correct direction. Wood calls this “near-idolatrous”: “conceiving a God who is interested in what shirt you wear can look a lot like inventing a God for your own small purposes.”

Evangelicals are aware. In his 2010 book Radical, megachurch pastor David Platt warned believers to be wary of making God in their own image. Jesus might begin “to look a lot like us because, after all, that is who we are most comfortable with. … [W]hen we gather in our church buildings to sing, and lift up our hands in worship, we may not actually be worshiping the Jesus of the Bible. Instead, we may be worshiping ourselves.”

Then there are the metaphysics. All Christian theologians must eventually puzzle through how YHWH, a distant, barely mentionable Creator, at some point presents as Jesus, “a God made flesh, who lived among us, who resembles us.” Is Jesus fundamentally our own image? A mere idea, created by humans to make life more bearable? In the face of life’s greater inconveniences, is belief just plain beneficial?

Maybe the actuality of God — where, what, how is He? — is less important than the results of believing. Formally this is called pragmatism. It doesn’t matter, the thinking goes, whether or not God is real. The point is to pray, to practice faith, and in doing so, God becomes real. In 21st-century terms, belief is a technology — a tool — for self-betterment. Pray, and you become enlightened, peaceful, sober, etc. It doesn’t matter what you’re praying to, or ultimately whether that thing even exists, so long as it helps.

I myself am uncomfortable with God. I have never seen or audibly heard from Him. And the existence of something I can’t see or hear feels dubious at best. But what I can say with certainty is that I have often felt better when I’ve prayed, and so I will continue to. God, if not actual, is useful. And yet, that approach makes God just another form of therapy. The idea is that His existence is negligible so long as you experience the benefits of belief or reap the rewards of an existential purpose or church community.

Wood ponders all this, and raises an excellent point: If God’s existence doesn’t really matter, then God, in a pretty major way, doesn’t really matter either. To Wood, prayer isn’t only “a technology or a practice. Prayer is also a proposition. It proposes that God exists and that we can communicate with that God.” From this perspective, there may be something worthwhile in agonizing over the actual existence of God. Hello …?, we ask, full of trepidation, or annoyance. While painful and anxiety-riddled, this hesitancy is at least about God, not just whether things are going your way.

Another problem with pragmatism is that it’s a ticking time bomb. While at times it might feel great to believe, at others, it might not. You might pray pray pray and still be depressed. At some point, God will turn your wife into salt, ask you to kill your only son, crucify your only hope for social change, permit mass starvation in Yemen, or in some other way incinerate any idea that belief is healthy, beneficial, or smart. These are all reasons that reasonable people can’t stomach faith. As often as God appears to be a friend, He also appears to be an enemy.

As for Jesus, anyone who has studied the accounts of his life knows that the Nazarene was never very pragmatic, nor convenient. No one followed him because it made them feel good. He rarely offered his disciples what they wanted, instead seeming to thwart their wishes at every opportunity. At no point did he express interest in the color of their clothes or the quality of their haircuts, though they might have liked him to. And while he did affect the weather, calming a storm, he incited terror in doing so, not an easy relief that the planned-for event could now go on.

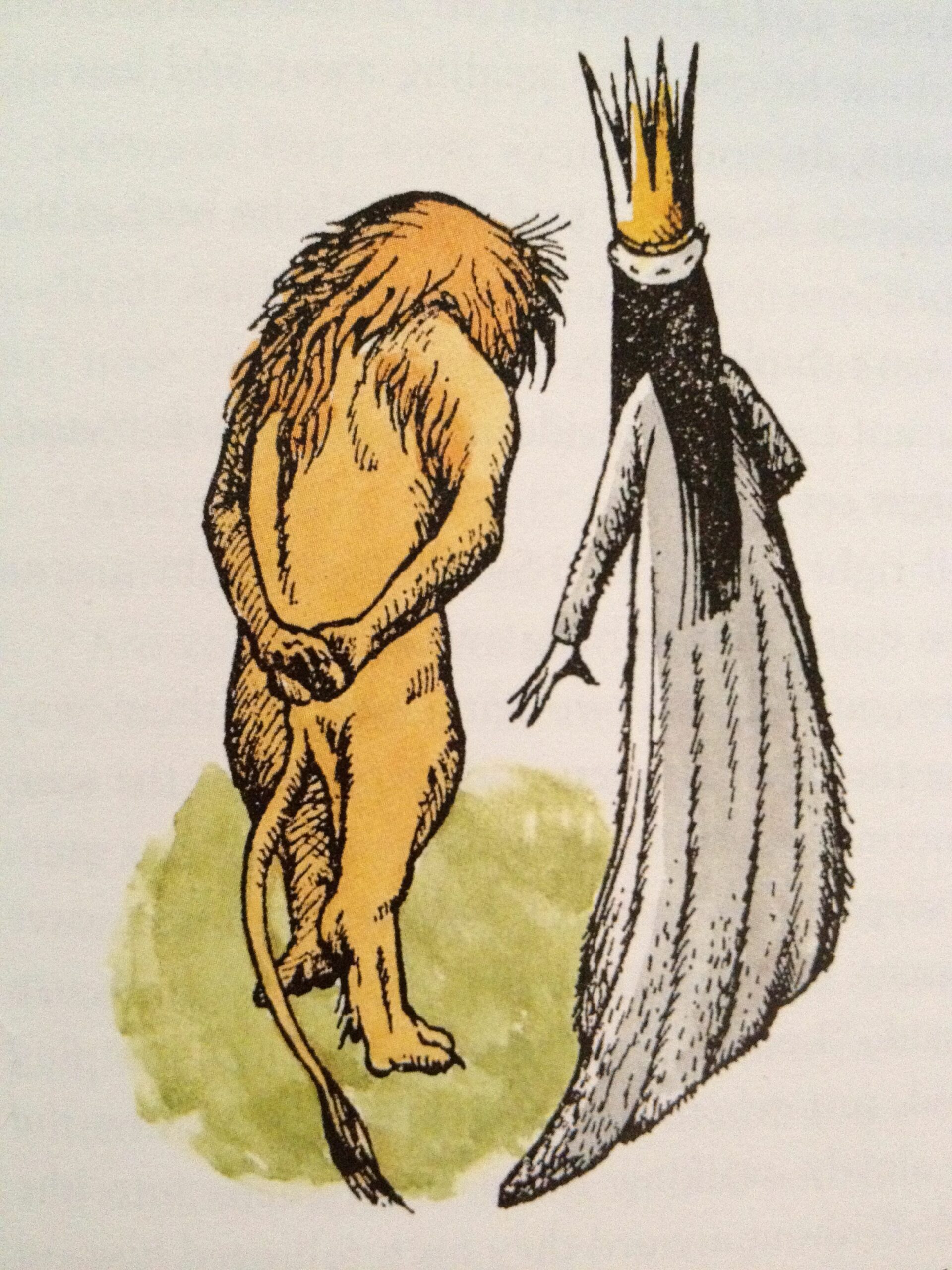

The great apologist C. S. Lewis had a knack for describing this wild, frightening character of God. In his Narnia books, the beloved Christ figure, a lion named Aslan, candidly admits that he has eaten children: “I have swallowed up girls and boys, women and men, kings and emperors, cities and realms.” As with Aslan, the voice of Jesus can sometimes be very, very awkward.

The great apologist C. S. Lewis had a knack for describing this wild, frightening character of God. In his Narnia books, the beloved Christ figure, a lion named Aslan, candidly admits that he has eaten children: “I have swallowed up girls and boys, women and men, kings and emperors, cities and realms.” As with Aslan, the voice of Jesus can sometimes be very, very awkward.

I guess what I’m trying to express is that if God were a humanistic mirage, He might be a little, uhh, nicer. He might sound more like a self-help manual, or a therapist. (Certainly, in much of Christendom, he is sounding more like these things every day.) But despite the human flesh of Jesus, the actual person seems ultimately unconcerned with our “small purposes” and utterly fixed on something wilder: love. Not kindness, as Lewis is swift to point out in his book The Problem of Pain, but love.

To describe God’s love, Lewis invokes many analogies — love of pets, love of a father for his son — but the most accurate analogy, he warns, is also “full of danger”; that is, the love “between the sexes.” The insanity, the out-of-control-ness of erotic love. This type of love is (and here Lewis quotes Dante) “a lord of terrible aspect”:

When Christianity says that God loves man, it means that God loves man: not that He has some “disinterested,” because really indifferent, concern for our welfare, but that, in awful and surprising truth, we are the objects of His love. You asked for a loving God: you have one. The great spirit you so lightly invoked, the “lord of terrible aspect,” is present: not a senile benevolence that drowsily wishes you to be happy in your own way, not the cold philanthropy of a conscientious magistrate, nor the care of a host who feels responsible for the comfort of his guests, but the consuming fire Himself, the Love that made the worlds …

This type of love is not convenient or pragmatic or even always kind. It may actually be unhealthy. It is possessive and unruly, bringing bad weather as often as good. Considered this way, Christianity, at least for me, is a lot weirder than my idols. And I idolize some pretty weird things. To my mind, an idolatrous religion would be somewhat tame, at least predictable. It would be like a mirror reflecting a mirror, where the image of the person standing there goes on for infinity, trapped. But Christianity is about breaking in, releasing the captives, even you, me. It is about the mirror shattering, flying apart at the worst possible time, right in your face.

COMMENTS

4 responses to “How Strange Is Your God? James Wood on the Idolatrous Voice of Christ”

Leave a Reply

!!!

“This type of love is not convenient or pragmatic or even always kind. It may actually be unhealthy. It is possessive and unruly, bringing bad weather as often as good. Considered this way, Christianity, at least for me, is a lot weirder than my idols.”

Take that, liberal Protestants, atheists, and fundamentalists!

Nadia Bolz-Weber once said that if she could be something cooler than a Christian, she would be, but she just couldn’t. The church definitely isn’t the death cult we asked for, but maybe it’s the death cult we need.

Shades of Bultmann

WOW cj, this is SO GOOD. i always appreciate the work of de-normalizing God.

Thanks a ton, Amanda! I appreciate it.