1. It’s a standard in job interviews to ask candidates about their biggest weakness. No one answers this question honestly, of course. You don’t get the job if you admit that you hold on to resentments for years. So you admit a faux weakness that really sounds like a strength: “I can be a bit of a perfectionist,” and everyone nods with approval. Employers tend to love a perfectionist. But to hear Leslie Jamison describe it in the New Yorker, perfectionism isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. Far from benign, perfectionism is a kind of invasive parasite that feeds on fear:

According to Hewitt, this is one thing that distinguishes true perfectionism from a mere pursuit of excellence: reaching the goal never helps, whether it’s a top grade, a target weight, or a professional milestone. Achievement, he says, “doesn’t touch that fundamental sense of being unacceptable.” Perfectionism perpetuates an endless state of striving. It’s an affliction of futility, an addiction to finding masochistic refuge in the familiar hell of feeling insufficient. It might not feel good, but it feels like home. […]

If we believe that the worst version of ourselves is the true one, we’re protected from being ambushed by our own inadequacy. Better to overestimate our flaws than to fail to see them in the first place. But this strategy is fundamentally isolating, leading us to create a brittle carapace of a “perfect” self that doesn’t need anything from anyone. Perfectionism estranges us from everyone else, Phillips argues, and traps us in endless conflict with ourselves: “We continually, if unconsciously, mutilate and deform our own character. So unrelenting is this internal violence that we have no idea what we’d be like without it.”

Researchers have noted that people with perfectionist tendencies, aside from DSM-5 mental health diagnoses, also have “higher than normal rates of ulcers, hypertension, fibromyalgia, arthritis, irritable-bowel syndrome, and Crohn’s disease, but they are also slow to seek care. Their fervent desire to ‘be O.K.’ (or to seem that way) can hinder them from looking for the help they need.” In other words, perfectionism isn’t just a personality quirk that might make you (arguably) better at your job. It’s deadly (see also, the plot of Black Swan …).

The root of perfectionism’s hastily-assembled façade, Jamison notes, is a lie with overtly religious overtones: “If I am perfect, then I’ll be loved.” So while some small measure of relief might be found by a self-imposed lowering of the bar — we’re all just human, after all — the solution to the justification by works downward spiral must come from outside this endless self-assessment. Back to Jamison:

Flett has come to understand mattering as a counterpoint to perfectionism, a more viable way to arrive at a sense of self-worth. One doesn’t have to be perfect; one just has to matter to someone. Indeed, feeling invisible or undervalued — a feeling Flett calls “anti-mattering” — is often what fuels a perfectionist’s neurosis. Flett’s first peer-reviewed paper on mattering, published in 2012, reported a significant correlation between anti-mattering and perfectionism among hundreds of university students. Perfectionism may arise as an attempt to overcome a sense of insignificance, but it’s a poor strategy, because each step toward perfection is a step away from distinctiveness, from the flawed, messy unrepeatability that we crave in others and want others to witness in us.

I’d quote the whole article here if I could, as Jamison outlines so many of the destructive symptoms of perfectionism. As an aside, it’s articles like the above that confirm my suspicions of attempts to pathologize writers who find grace to be such a transformative idea (cf. Martin Luther and Augustine before him). Far from a relic of antiquity, it turns out justification by faith is as vital as ever.

2. Speaking of the crippling effects of perfectionism, Maytal Eyal’s “Enough With the Mom Guilt Already” checks in on how mothers are handling all the pressure. Not from their spouses, but the field of psychology. In 1951 the psychoanalyst René Spitz claimed that “the mother’s personality, acts as a disease-provoking agent, a psychological toxin.” While few today would be so blunt, the belief that “good parenting” determines the course of a child’s life carries with it a dark implication:

Mother-blaming never really disappeared; it just changed shape. Now psychologists don’t accuse moms of causing schizophrenia or autism. Still, you might hear some talking about “trauma” and “attachment wounds.” This kind of language may sound more compassionate. But a common implication remains: Moms, if you screw up early on, your kids will carry the consequences forever. […]

Many of us have internalized the theory that who we are and the reasons we suffer are largely determined by how we were raised — and that our failures, relationship problems, and inability to set boundaries can be traced to our parents, especially our mothers. It should come as no surprise, then, that for many women, motherhood is suffused with anxiety and guilt. […]

To be clear, I’m not arguing that moms shouldn’t work on their own mental health, or that they shouldn’t think deeply about their approach to parenting. Rather, I worry that therapy culture prompts mothers to gaze obsessively, unhealthily inward, and deflects attention from the external forces (cultural, economic, political) that are actually the source of so much anxiety. When mothers chase psychological perfection, the result is rarely joy or any semblance of mental health. Instead, too many women are left with the gnawing feeling that, no matter how hard they work, they are likely to fall short — an outcome that benefits neither parents nor their children.

What will rescue us from this generational blame game? A mutual admission of shared fault might be a good start, from both parents and their kids. But that would fall short of relational repair. Diagnoses only get you so far. Better still to reach for something beyond deserving, to a forgiveness that undermines our need for blamelessness altogether. What we most need, writes therapist Abraham Nussbaum in Plough, is a healthy dose of something more than therapy:

There is no cure for being human, not even therapy. Part of why you need to leave the house every day is because we are never fully at home on this earth. Sharon, like me, needed something beyond therapy to fully shift her perception. We all need a mercy beyond the ability of an ally, coach, or teacher, something beyond the limits of our imaginations.

3. This next one on friendship can sound a bit trite, or the kind of wisdom everyone nods their heads about. But at the same time, the kind of friends Ray Ortlund describes seem few and far between, dependent upon the fickleness of shared interests or the randomness of proximity. They might not feel like they are transactional or somehow conditional, but they probably won’t see you through when you hit rock bottom. “What’s a real friend?” Ortlund asks. “Answer: an honest-to-goodness friend is all in.”

Not everyone sticks around. Some people we thought were friends just aren’t there for us when everything is on the line. And that’s when rock bottom is more than just sad. It’s terrifying.

To be discarded and forgotten, canceled and deleted — our sense of worth shatters. We realize, They never were my friends. I never understood what was really going on. How could I have been so blind? Yet all the while, their happy parade continues moving on down the street, the trumpets blaring and the drums beating, as if we never even existed. Because we didn’t. Not to them. Not really. […]

True friendship isn’t a cost-benefit calculation. It’s personal commitment, even when everything falls apart — especially when everything falls apart. Isn’t that the best part of friendship? We might forget that happy Fourth of July cookout with friends last year. But we’ll never forget the night they rushed to the hospital after our terrible car wreck, how they stayed with us through the ordeal. God is like that. He’s all in with you, as your closest friend, at all times.

Ortlund illustrates precisely the kind of “mattering” Jamison believes to be the antidote to perfectionism. What we need in failure isn’t a guide for how to climb out of rock bottom, but someone there with us regardless of our circumstance.

4. Lots of talk these days on the impending AI apocalypse/utopia. As months have turned to years, I’ve found myself bored by the whole debate. My own two cents? I think several years down the line we’ll figure out what the actual market uses of AI are (i.e., not writing term papers for college students), and we’ll wonder what else we could have done with the trillions of dollars we burned along the way. But don’t tell that to the AI-hype machine, who exists to justify such a cash expenditure. To them, as Freddie deBoer recognizes, the machines will save the world from itself, which is the kind of belief that sounds a distinctly religious register.

This period of AI hype is built on twin pillars, one, a broad and deep contemporary dissatisfaction with modern life, and two, the natural human tendency to assume that we live in the most important time possible because we are in it. Our ongoing inability to define communally-shared visions of lives that are ordinary but noble and valuable has left us terribly frustrated with the modern world, and our sclerotic systems convince us that gradual positive change is impossible. Hence pillar one. And the very fact that we have a consciousness system, the reality of our lives as egos, of dasein, makes it very difficult to avoid thinking that we live in a special place and special time. Hence the second pillar. I’m not assessing character here; the solipsism of consciousness is inherent, and our nervous systems are set up to make us feel that we are the protagonists of reality. I too have to remind myself that I don’t live in a privileged time. But I think adults do need to fight the temptation to think that way, and unfortunately the limitless sci-fi imaginings that artificial intelligence invites has made this habit irresistible to many. […]

What Alexander and Mounk are saying, what the endlessly enraged throngs on LessWrong and Reddit are saying, ultimately what Thompson and Klein and Roose and Newton and so many others are saying in more sober tones, is not really about AI at all. Their line on all of this isn’t about technology, if you can follow it to the root. They’re saying, instead, take this weight from off of me. Let me live in a different world than this one. Set me free, free from this mundane life of pointless meetings, student loan payments, commuting home through the traffic, remembering to cancel that one streaming service after you finish watching a show, email unsubscribe buttons that don’t work, your cousin sending you hustle culture memes, gritty coffee, forced updates to your phone’s software that make it slower for no discernible benefit, trying and failing to get concert tickets, trying to come up with zingers to impress your coworkers on Slack … And, you know, disease, aging, infirmity, death.

A magic box that will fix everything? Sounds like the plot to “The Monkey’s Paw” to me, but I’m just a humble humanities scholar. Still, one would hope that the technological utopians would have learned something from the Millerites, the Harmonists, the Branch Davidians, the Montanists, or the Shakers. There’s a fine line between hoping for the imminent salvation of the world and desiring its destruction.

5. And now for something entirely different, the funny side of the internet produced a few gems this week. Over at the Hard Times, “Crying Baby on Flight Speaks for Everyone” sounds about right to me. As does Points in Case‘s “What I Hope My Dentist Will Say to Me When I Visit for the First Time in Six Years.” And good Bible humor is hard to find, but I had a good laugh at the Bee’s “Apostles Quickly Start Acting Pious As They Notice Luke Watching And Taking Notes“:

Apostles Paul and Silas, in the middle of a long missionary journey, found themselves having to straighten up and act more serious after they were joined on this leg of the trip by their physician friend, who was apparently now documenting everything they did and said.

“Oh, sorry, didn’t know you were writing all of this down,” Paul reportedly said to Luke. “So, um … yeah … forget the story I was telling about the time Barnabas spent an hour preaching the Gospel with a piece of fish stuck in his beard from lunch. Let’s talk about real, serious stuff now. Just leave that part out, yeah? Luke? What are you doing? Are you still writing everything I’m saying? Even this? And this?”

“They seemed like they were a lot more careful,” said one witness. “They’re normally really loose and laid-back, but once they saw Luke over there taking notes about the whole meeting, they started acting different. Way more serious all of a sudden.”

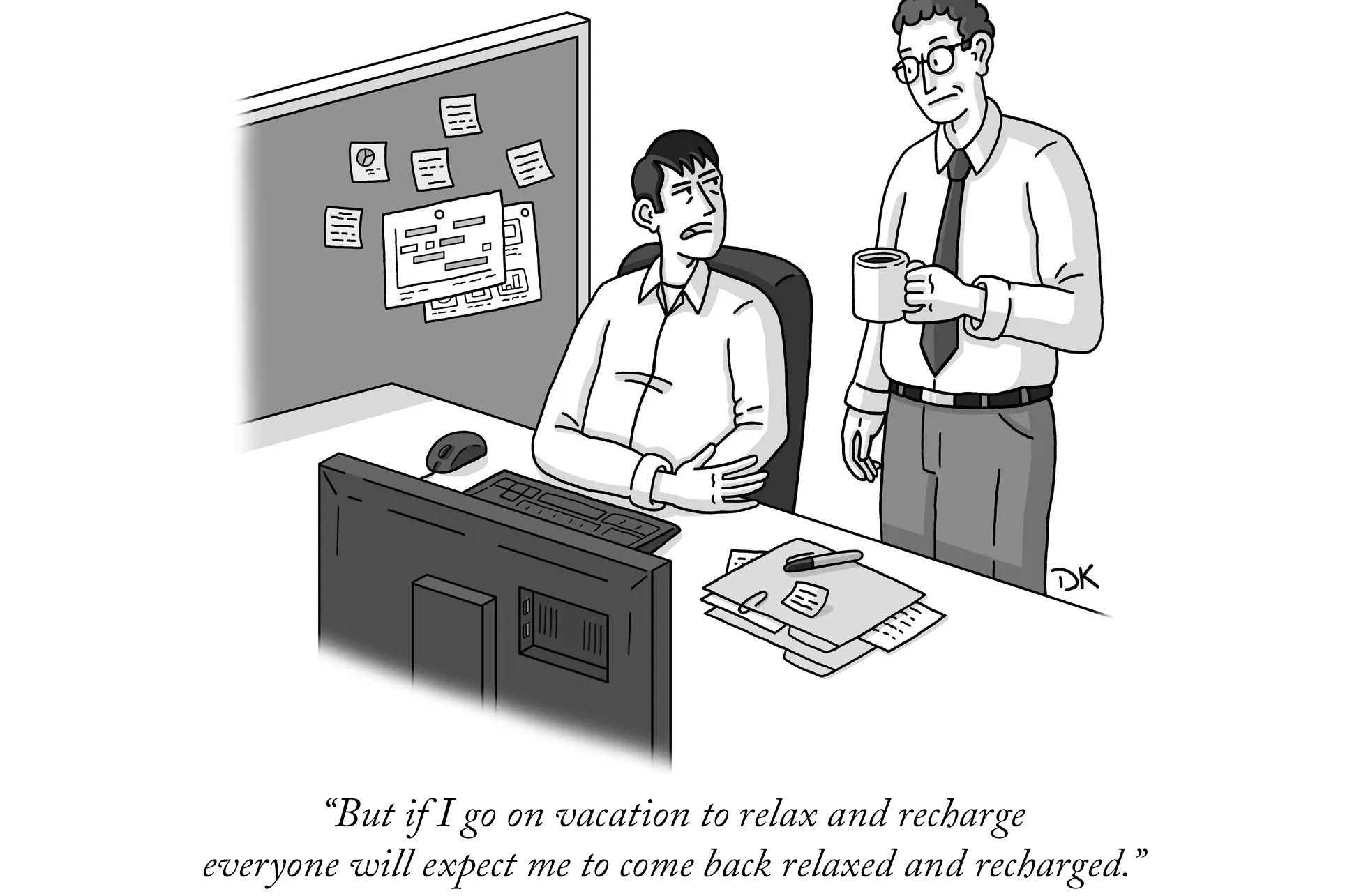

6. I was recently asked whether I was ready for fall to begin. Why, no, I am not. Behind the question is certainly a friendly desire to commiserate, but I also couldn’t help but hear tinge of warning. That the summer’s reprieve from efficiency is over and I better be ready to return to “real life.” But maybe it’s the other way around? Maybe inefficiency is true to how life should be? It is certainly true of God, writes Kelly Kapic for Christianity Today in “Unlearning the Gospel of Efficiency,” reminding us that “God’s highest value is not efficiency, especially not in any simple or mechanistic sense. It is love:

This mechanistic push for ever-increasing productivity, maximum efficiency, and personal convenience acts like sandpaper on our souls. We long instead to take time for intimacy, belonging, and healthy dependence. Yes, sloth and neglect can be painful and destructive for human flourishing, but so are relentless demands to maximize productivity.

Our Creator is neither lazy nor tyrannical. Instead, he is wise, compassionate, and purposeful — and this should shape our vision of faithfulness. The God who was comfortable taking his time during his original process of creation is the same God who is comfortable doing the work of his new creation in us over time. Gently yet confidently, we must remind ourselves that “he who began a good work in you will carry it on to completion” (Phil. 1:6).

God does not promise us instantaneous change or victory; he promises that he is working, that he will not let us go, and that he has a longer view than we do. May his patience and perspective give us the courage we need for this day, this month, and this lifetime.

Strays:

As to #1, maybe employers should stop asking that stupid question. But here are a few answers when it happens: 1) Job interviews 2) I applied here. I’m desperate 3) Carbs 4) This question.