This essay appears in Issue 26 of The Mockingbird print magazine.

By his account, Joshua Blahyi met Jesus right after killing a child whose blood was still on his hands. Jesus told Blahyi, “Repent and live or refuse and die,” and Blahyi wanted to live. He’s a pastor now. Blahyi had killed more than a few children at that point in his capacity as a Liberian warlord known as “General Butt Naked” (so named for his habit of going into combat with himself and all his forces unclothed). At the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, following the Liberian civil war, Blahyi testified that he had killed “not less than twenty thousand” in his lifetime. Whatever you make of that figure, it is undeniable that he killed a lot of people. But now Blahyi works to rehabilitate former child soldiers. He preaches every Sunday. He spends every Friday fasting and praying. He travels around the country apologizing to the families of people he killed.

It is easy to doubt Blahyi. His claims are absurd. He seems to revel in his newfound fame. But even apart from these suspicions, is it possible to imagine someone like Blahyi really converting? A murderer can repent, maybe, but can they ever truly be anything but a murderer?

Blahyi offends so deeply in part because we have forgotten the figure of the convert. Of course we have, because the convert is the most unmodern of figures. The convert cannot quite appear within our common categories. By “convert,” I mean only: a person who changes completely, who swears off their old self and embraces a new one. One need not adopt a new religion to convert. Indeed, people change religions all the time without converting. Consider someone who picks a religion only for its aesthetics or philosophical tradition. This “convert” already liked those things, so they joined the team that expressed their preferences. Nor do major shifts in one’s political or ethical outlook necessarily signal a conversion. If I disavow my liberalism and become a socialist because I come to believe that socialism better respects the equality of all human beings, I haven’t converted — I have only re-assessed the logical consequences of beliefs that I already held. Regardless of how radically I appear to have changed, if the explanation for that change is within me (my desires, my beliefs, my reasoning), then I have not converted. I have simply made my pre-existing self more coherent.

Our resistance to the convert surfaces in popular deterministic explanations of personality. Consider what astrology and scientific psychology have in common. Whether you root your interpretation of someone’s character in their childhood trauma or in the stars, both explanations are unchanging: a person will always have been abused, a person will always be a Leo. At this level, conversion simply isn’t possible. A person may express their immutable self differently, more “authentically,” but that self doesn’t change. One might also start to hide that immutable self — it’s easy to imagine Joshua Blahyi as a wolf who finally found his sheepskin.

But what if Blahyi is sincere? If he is, that sincerity cannot be explained — neither psychologically, sociologically, nor astrologically. If he is sincere, his conversion speaks for itself and we cannot understand it. The convert troubles us because they cannot be made rational. The convert cannot be predicted; perhaps they cannot even be imitated. But the convert, if they exist, must at least be conceivable. So how could conversion be possible?

***

Blahyi’s life cannot help us determine what would make conversion possible. It has been subject to too many fabrications to be useful. We will have better luck working with pure fabrication rather than the fickle stuff of real human life. Fiction will serve just fine to examine conversion as a possibility. (And as the sticky problem of Blahyi’s believability suggests, conversion might only ever be visible as a possibility — its actuality can always be doubted.)

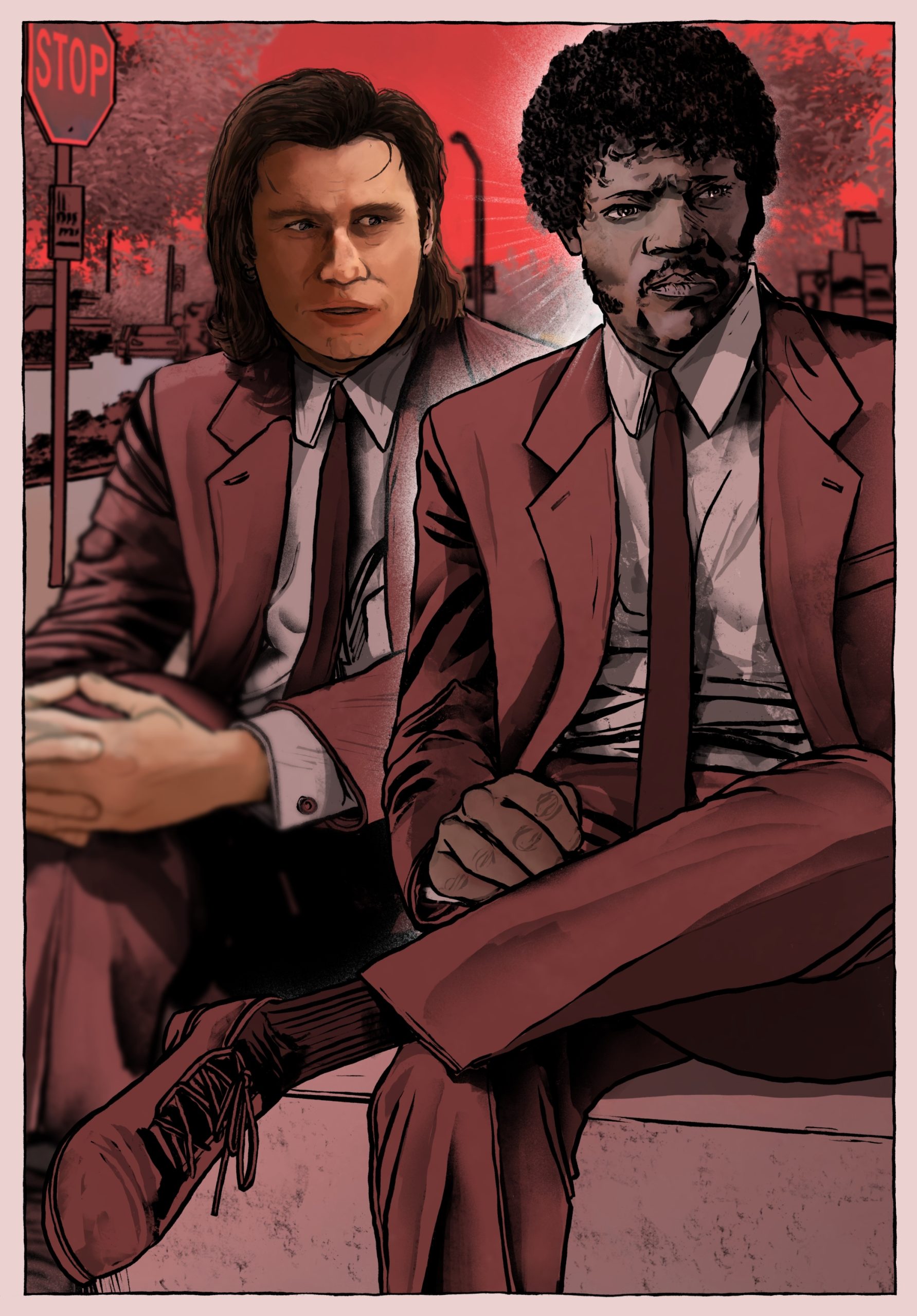

Illustration by Julius Maxim.

Perhaps the most popular conversion movie in the past half-century is Pulp Fiction. The film runs several plots together, but it’s book-ended by the misadventures of two hitmen: Jules (played by Samuel L. Jackson) and Vincent (played by John Travolta). By the end of the movie, Jules seems to undergo a genuine conversion from gun-for-hire to man of God. But Vincent remains the same, finding Jules ridiculous. Both are faced with the same event: in the middle of a job, a man bursts out of the bathroom and empties his revolver at them. They are unscathed; the bullets seem to have gone directly through them. Vincent judges the near-miss to be unremarkable, a cosmic accident (as everything seems to be from his perspective). As he puts it, “This shit just happens.” Jules responds, “This shit doesn’t just happen,” judging it a miracle and finding himself in an entirely new world. And nearly immediately after the miracle, Jules declares that he’s done killing people — God must have intervened to stop the bullets and now Jules must go along with God’s ways. Why does Jules convert and Vincent remain stagnant?

It is tempting to explain Jules’ conversion psychologically — the scene building up to it invites this sort of explanation. Before Jules and Vincent are spared, Jules executes a man named Brett. Aiming his gun at Brett, Jules riffs on scripture. He claims to recite Ezekiel 25:17, but elaborates the actual passage considerably: “The path of the righteous man is beset on all sides by the inequities of the selfish and the tyranny of evil men. Blessed is he who in the name of charity and goodwill shepherds the weak through the valley of darkness, for he is truly his brother’s keeper, and the finder of lost children. And I will strike down upon thee with great vengeance and furious anger those who attempt to poison and destroy my brothers. And you will know my name is the LORD, when I lay my vengeance upon thee!” Then bullets. When Jules recites the verse, he is, of course, the LORD. When Jules recites the first-person pronouns, he means himself. Jules encounters God because he plays God.

Psychologically interpreted, Jules’ conversion would need to be seen against the non-conversion of his partner and foil, Vincent. Compared to Jules, Vincent seems almost humble: he does his job and doesn’t think about it. No theological theatrics, no metaphysical speculation, just duty and cynicism. For a hitman, Vincent is remarkably self-effacing. At dinner with Mia Wallace (his boss’ wife whom he’s charged with entertaining), he says nearly nothing of himself. And when Vincent asserts himself late in the film to Wolf (the cleaner hired to take care of Vincent’s mess), he does so casually, asking only, “Could you say ‘please’?” and backpedaling as soon as Wolf resists. Vincent is an unbothered everyman. Even in his moment of moral tribulation (will he allow himself inappropriately close to Mia?), all he has to say for himself is, “You see, this is a moral test of oneself, whether or not you can maintain loyalty. Because… being loyal is very important.” Indeed, one might envy Vincent’s unreflective calm. He is the film’s most human character: of the seven scenes taking place in the bathroom, Vincent is in four. We even see him on the toilet. He is fleshy and vulnerable and anything but special and he knows it, yet somehow it does not bother him. (Vulnerability seems to bother Jules — what else would he need the grandstanding for?) Superficially, Vincent’s way of being resembles the self-forgetting of the pious. But it has a different source — unlike the religious, Vincent is a man without need.

His cool self-assurance comes from having everything he needs within himself. This is why he makes such an attractive audience surrogate (and he is the character we are meant to identify with — Vincent gets the lion’s share of the screentime): he plays out our fantasies of self-sufficiency. What could he possibly need God for?

Vincent in his detachment is unreachable. Jules in his prideful fury still needs. So God shows up to say “Remember me!” and Jules hears God and Vincent doesn’t. Or they get lucky (whatever that means) and the bullets pass through them due to some set of complicated natural circumstances and Jules’ need deludes him and Vincent’s calm keeps him clear-eyed.

But as compelling as these psychological considerations might be, do they really explain why Jules converts? If Jules’ response to the miracle was determined by his psychological character, doesn’t his “conversion” simply become a necessary outcome of what he already was on some level? If that’s so, then Jules’ “conversion” would only be an expression of his basic being. Nothing would fundamentally have changed. And if Jules’ reaction to the miracle was determined to happen, how could he be responsible for it? If he could not have seen God and said “no,” then how could we consider it to be his conversion? If psychology determines everything — that is, if one simply is a Jules or a Vincent for reasons entirely biological, historical, and cultural — then all action, even and especially in matters profoundly ethical, can only be reflex. A choice fully explainable is not truly a choice but rather only a revelation of the inevitable. Affirming conversion means rejecting all determinisms.

***

Whether a miracle happened or not, Jules and Vincent can’t stop talking about it. Arguing in the car afterward, Vincent turns and asks Marvin (their informant), “Do you think God came down from heaven and stopped—” and then Vincent’s gun goes off, festooning the interior of Jules’ Chevy with Marvin’s brains. Jules, understandably, wants to know why Vincent shot Marvin in the face. Vincent says the car went over a bump. Jules insists that there was no bump — and certainly no bump is visible to the viewer. Nonetheless, Vincent insists it was an accident — and certainly it did look like an accident. They are, of course, still talking about God and the bullets. As a viewer, and probably as Jules and perhaps as Vincent (and definitely as Marvin), it is impossible to ascertain why Vincent shot Marvin. But it is difficult to make sense of the film without trying to.

Illustrations by Melisa Gerecci.

One way to make sense of the film is to assert that it is senseless. Pulp Fiction is frequently described and derided as “postmodern.” Literary critic James Wood’s diagnosis is exemplary: “[Tarantino] represents the final triumph of postmodernism, which is to empty the artwork of all content, thus voiding its capacity to do anything except helplessly represent our agonies (rather than to contain or comprehend). Only in this age could a writer as talented as Tarantino produce artworks so entirely vacuous, so entirely stripped of any politics, metaphysics, or moral interest.” Postmodernism, for Wood, is the breakdown of representation. On this view, Pulp Fiction appears as a kaleidoscope of cultural symbols all only pointing at one another: violence for violence, kitsch for kitsch; mere timeless worldless entertainment; a dog eating its vomit; a tale told by an idiot, signifying nothing.

The absurd, apparently meaningless violence in Pulp Fiction is an especially frequent target for criticism. David Foster Wallace asserted that Tarantino is a cheap imitation of David Lynch, whose “violence always tries to mean something” while Tarantino’s does not. As Wallace had it, “Quentin Tarantino is interested in watching somebody’s ear get cut off. David Lynch is interested in the ear.”

And yet the incident with Marvin seems to dramatize this whole issue, contradicting both Wallace and Wood. In the script, Vincent asks Marvin, “Do you think God came down from Heaven and stopped the bullets?” but in the film Vincent stops with the word “stopped” and the words “the bullets” are replaced by the bullet in Marvin’s skull. Words become things; Vincent “accidentally” acts out his language. In the most bloody, direct way possible, the film asserts the reliability of signification: “bullet” means bullet. And isn’t this in itself a rebuttal of Wood’s claim that the film is devoid of metaphysics? Certainly, whether God is involved is left ambiguous, but the fact that there is a world out there to which things refer has been affirmed and underlined. This is the most basic kind of metaphysical claim, and for that reason the most important kind, too.

Whatever else Vincent shooting Marvin means, the incident is, perversely, an affirmation of the possibility of meaning. Not very “postmodern,” at least in the sense that Wood intends the word. To advance meaning but then to leave it indeterminate and let the viewer decide, well, that’s just art. Language cannot but be ambiguous, but ambiguity is not emptiness.

After they’ve dealt with Marvin’s corpse, Jules and Vincent grab breakfast. They continue discussing the miracle — Jules declares that he’s a changed man, that he’s felt God’s touch and that he’s going to reform. He was, he concludes, spared for a reason, and his duty now is to remain receptive to God’s will. Vincent stays skeptical. Vincent punctuates their argument with a visit to the bathroom, during which a couple of fellow diners try to rob the place. Instead of killing them, as pre-miracle Jules certainly would have, post-miracle Jules deescalates the situation. With his gun pointed at one of the would-be robbers, Jules again recites “Ezekiel 25:17,” but he doesn’t shoot him. He tells the robber that he used to think the verse was “just a coldblooded thing to say to a motherfucker ’fore you popped a cap in his ass” but that the miracle he experienced that day made him reconsider. He then tries out a couple interpretations of the passage: “It could mean you’re the evil man. And I’m the righteous man. And Mr. .45 here, he’s the shepherd protecting my righteous ass in the valley of darkness. Or it could be you’re the righteous man and I’m the shepherd and it’s the world that’s evil and selfish.” But he rejects both interpretations as easy and self-serving. Instead, “The truth is, you’re the weak. And I’m the tyranny of evil men. But I’m tryin’. I’m tryin’ real hard to be the shepherd.” Jules has been carrying his own condemnation within him for years and only now realizes it. And that realization frees him from his evil way of life.

Jules’ conversion might seem cheap. It seems even cheaper with the source of his distorted verse in mind. Viewers of Pulp Fiction typically assume that Tarantino directly embellished the Bible verse, since the actual text isn’t as dramatic and wouldn’t set up Jules’ conversion at the end. But Tarantino didn’t write the distorted verse at all — it’s lifted almost word for word from the beginning of the karate movie The Bodyguard. Interior to the film, then, we should assume that that’s where Jules learned it. Jules is converted by a movie, by mere entertainment. As Gary Groth interprets this conversion scene in The Baffler, “When Samuel Jackson’s Jules finds God and gives Tim Roth his revelatory speech at the end of the film, we realize even God has been reduced to a character in a sitcom.”

But why would God be less present in a sitcom than anywhere else? Meister Eckhart wrote that “When [you] think that [you] are acquiring more of God in inwardness, in devotion, in sweetness and in various approaches than [you] do by the fireside or in the stable, you are acting just as if you took God and muffled his head up in a cloak and pushed him under a bench.” If God is, God is in sitcoms. God appearing to Jules via murder and a B movie does not make God’s appearance any less probable. You can doubt any revelation, any conversion, even the grandest ones: Luther’s raving about the thunderstorm was just superstition, Augustine’s agony in the garden was only psychopathology, etc. History’s great conversions are no more or less legitimate than Jules’. Indeed, conversions cannot be compared or judged at all because conversion doesn’t take place on the outside. Conversion is a matter of the heart; it is necessarily invisible. The triviality of the karate film and Jules’ abhorrence of his former life show you nothing of his heart. Likewise, the absurd violence and endless pop culture references show you nothing of the heart of Pulp Fiction — the film doesn’t have a heart, it’s just images on a screen. You’re the heart in this equation. The film, like any film, will show you a little bit of what goes on inside you. Likewise, the conversions of others can only throw us back on ourselves, to consider whether we have converted or whether we want to or whether we think we even could.

***

The real Ezekiel 25:17 reads: “I will execute great vengeance on them with wrathful rebukes. Then they will know that I am the LORD, when I lay my vengeance upon them.” In this passage, God expresses what is perhaps His greatest concern in the prophecy he transmits to Ezekiel: that God should be recognized. In the book of Ezekiel, God says some variation of “You shall know that I am the LORD” more than 70 times. And we shall know that God is the LORD mostly by the destruction He brings: razed cities, dead idolators, etc. But why is destruction God’s preferred method of gaining recognition? Because He is trying to effect a conversion. God stresses that even the wicked will live if they repent. “Cast away from you all the transgressions that you have committed against me, and get yourselves a new heart and a new spirit! Why will you die, O house of Israel? For I have no pleasure in the death of anyone, says the LORD God. Turn, then, and live” (18:31–32). Convert or die! And the precondition of conversion, as the God of Ezekiel sees it, seems to be destruction. One cannot become something else without the destruction of what one already is. And this kind of destruction has to come from without — that’s why it’s God’s business. If you destroy yourself, if you try to seize a conversion when one has not been offered to you, your destruction is still only an expression of what you were. Conversion is something done to you as much as it is something you do.

And the God of Ezekiel insists that nearly everything is God’s doing. God insists, “All the trees of the field shall know that I am the LORD. I bring low the high tree, I make high the low tree; I dry up the green tree and make the dry tree flourish. I the LORD have spoken; I will accomplish it” (17:24). God can make of things whatever God likes. God works according to strange purposes, delighting in making things what they are not. So things are what they are only because God wills it — with perhaps and only perhaps the exception of the warped wood of human character, which seems to have its own will. Unlike the low tree made high, the people of Israel seem to need to cooperate with God’s designs. Unlike the low tree made high, the people of Israel have a will to give up. That will might be nothing in comparison to God’s magnificence, yet God still seems interested in their turning, their converting. “Turn and live,” God says, not, “I will turn you and you shall live.” But regardless of who effects the turning, its precondition is still God’s action. This is what Jules learns when God spares him: that his own will, his own designs, are worthless. He cannot live on his own credit. And if Jules does not sustain himself, he is not who he thought he was.

And the God of Ezekiel insists that nearly everything is God’s doing. God insists, “All the trees of the field shall know that I am the LORD. I bring low the high tree, I make high the low tree; I dry up the green tree and make the dry tree flourish. I the LORD have spoken; I will accomplish it” (17:24). God can make of things whatever God likes. God works according to strange purposes, delighting in making things what they are not. So things are what they are only because God wills it — with perhaps and only perhaps the exception of the warped wood of human character, which seems to have its own will. Unlike the low tree made high, the people of Israel seem to need to cooperate with God’s designs. Unlike the low tree made high, the people of Israel have a will to give up. That will might be nothing in comparison to God’s magnificence, yet God still seems interested in their turning, their converting. “Turn and live,” God says, not, “I will turn you and you shall live.” But regardless of who effects the turning, its precondition is still God’s action. This is what Jules learns when God spares him: that his own will, his own designs, are worthless. He cannot live on his own credit. And if Jules does not sustain himself, he is not who he thought he was.

Of course, Pulp Fiction can’t show whether Vincent or Jules has the correct view of the cosmos or of these two characters. But it does make some suggestions about the consequences of their cosmologies. Vincent the humble hitman does not repent — he is shot to death not long after he denies the miracle. We don’t see what happens to Jules, but we have seen him change. He abjures violence. And he seems to become humble in a way that is not even comprehensible from Vincent’s position. For what is more humiliating: to be a nothing bopping about in the cosmic churn, or to be a child of God who spat in God’s face? Humility is a relation — if there is nothing, then you cannot be nothing, because there is nothing to be nothing before. And if you can’t become nothing, how could you possibly become something else?

***

It might seem like scientific psychology and “postmodern” thought both prove that we don’t belong to ourselves. The first locates our being in our history and our biology — things that are ours yet operate beneath and beyond our conscious will. The second diffuses us: in the “postmodern” understanding we are a concatenation of interpretations, all always revisable, because what we really are (if there is such a thing) can never appear to us. But in removing us from ourselves, both modes of thinking offer a certain security. Contemporary psychology hands us a solid self, made of neurotransmitters and trauma and genetics and cultural scripts. And “postmodern” styles of thought tend to emphasize self-fashioning (Butler, Foucault, etc.): we might not have an immutable self to express, but we are never without the opportunity to remake ourselves. Neither of these models of the human person have room for commitment, which is the essence of conversion.

Psychology reminds us of certain immutables, sure — but those immutables are only given, never chosen: personal history, biology, “the authentic self.” And such immutables do not make moral claims on us — I could be naturally aggressive, but that would have nothing to do with whether I should be violent. A commitment to nonviolence must be formed, it must be assented to. Or I might discover that I’m an introvert or a sociopath. But these categories represent only a recognition of what I already was; they do not tell me what I can or should be. And not only does the psychological interpretation of the human being not impose commitments, it can also transform existing commitments into mere expressions of the self. Consider a therapist who suggests that the best thing for their client is to remain with their marriage — it’s not the marriage that binds, but the pre-existing claims of who the client is. A marriage might always be judged as either healthy or unhealthy, but the needs of the true self by which it is judged are unchangeable. There is no commitment that is not already determined by the given essence of a person.

Postmodern self-fashioning precludes commitment even more clearly: to the extent that the self is revisable, it’s not committed. One does not become sober or a parent or a Christian conditionally. It would be hard to call someone truly sober who says that they’ll continue to abstain from alcohol so long as they feel like it. It would be hard to call yourself a parent if tomorrow you can decide not to be. Certainly most “postmodern” philosophers are not advocating for anything like parents abandoning their children. But when you suggest that the self is a fiction, it takes some serious philosophical legwork to avoid reducing commitments to fictions as well. Thinkers like Judith Butler and Jacques Derrida may have excellent theories about how a non-substantial self can still be ethical, but that nuance tends to get lost in their actual cultural influence. In practice, undergraduates tend to be impressed with the revelations that everything is socially constructed, that language is arbitrary, that truth is an ideological imposition. These ideas then tend to be put in service of the expressive individualism that undergirds most of our culture’s most sacred dictums (e.g. “Be yourself!” “Find yourself!” “Take care of yourself first!”).

Conversion is a paradox: it means changing into something unchanging. It can be thought only with certain metaphysical presuppositions in place. There must be a real solid self and that self must not be entirely determined. And another paradox: there must be something wholly other than the self that can still reach it. If conversion is possible, we must be the sort of creatures that can be broken into, and there must be something capable of breaking into us.