The Mockingbird is a nonprofit print magazine that seeks to connect the message of God’s grace with the concerns of everyday life. By our definition, grace is dynamic, unmerited, and expansive; we hope the range of voices in this journal reflects that understanding. We welcome writing from all perspectives in an effort to express, in surprising and down-to-earth ways, the freedom that is central to our belief. Our pages have featured award-winning illustration, poetry, and writing from novelists, priests, theologians, psychologists, armchair experts, and beyond.

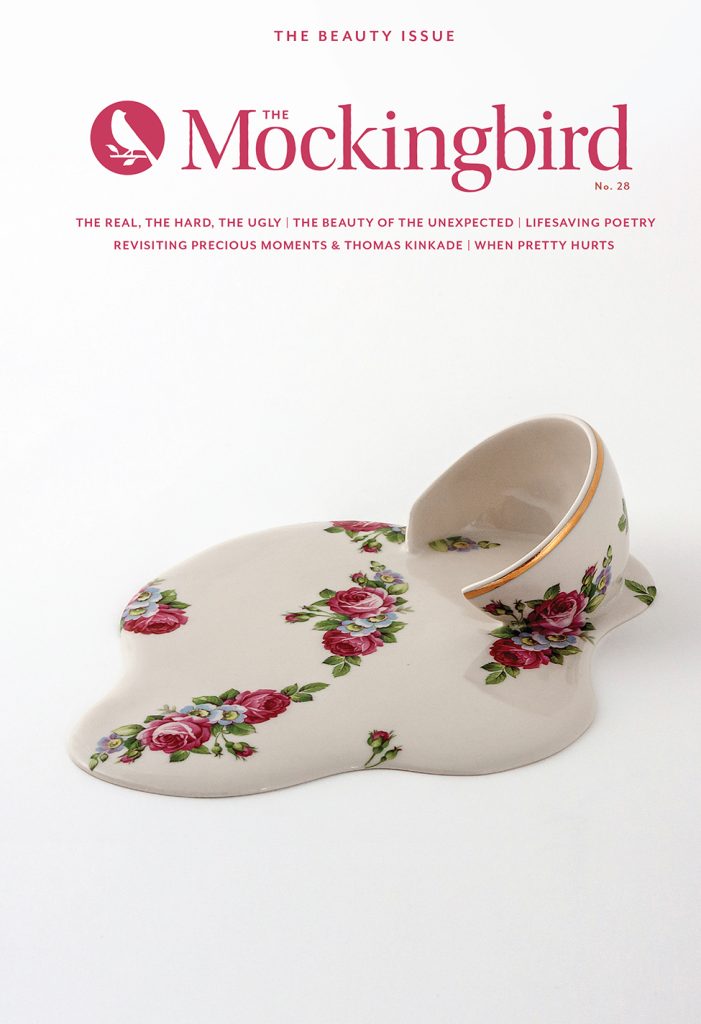

The Beauty Issue Is Now Available!

“Who were you to decide what was beautiful? Things are beautiful if you love them.” —Jean Anouilh (1950)

Imagine a preacher’s kid struggling to find his purpose in life. Beginning at age sixteen, he gets a job in the “art world” at a gallery. But in his twenties, he’s pretty sure contemporary art has sold out to commercial incentives, and so, frustrated (and also expecting to be fired), he resigns. He tries other jobs, but none stick. He tries bookselling but finds it dull; he tries theology school but fails the entrance exam; he tries lay preaching but fails the final exam; he goes to a coal mining town to serve the poor, but, despite his best intentions and committed efforts, his contract is not renewed. His personal life is, somehow, worse. He proposes to three women, is roundly rejected by each, moves in with a pregnant sex worker, and that relationship doesn’t last either. Meanwhile he paints—he has become an obsessive painter—but survives on his brother’s money, selling only a few drawings and one painting in his lifetime. After a striking act of self-harm—lopping off an ear—he continues to paint daily, mostly from a psych ward, and with little encouragement. His palette grows more vibrant even though his prospects do not. Ultimately, he takes his own life.

As you’ve probably guessed, this is the broad-strokes tale of Vincent van Gogh, whose work now draws over two million visitors every year to the Amsterdam museum devoted to it. His orchards, cypresses, and starry nights, so laced with hope and pathos, bear a rich and singular beauty. A hundred years after he painted the “Portrait of Doctor Gachet,” it sold for 82 million dollars.

The point is not that he was a misunderstood genius. It is that beauty operates on its own terms. Beauty cannot be coerced from an artist nor from the market; no one can force the beholder to see it. It seems only miraculous that what Van Gogh made from his labyrinth of dejection attests, generations later, to a kind of beauty that he himself may not have recognized.

Beauty, like grace, arrives mysteriously. It surprises. A reminder of God’s presence in the world, beauty functions as grace itself. As such, it can manifest through conventionally ugly means. A dim shelter for the unhoused. Recovery meetings in a church basement lined with Calvinist Bible commentaries. An embarrassing apology.

The centerpiece of the Christian faith, the cross itself, is the most beautiful ugly thing there is—a life sacrificed.

This is what religious people so often get wrong about beauty. They think it is one’s responsibility to create; the dogmatic keep a tight leash on what’s “acceptable.” Easily digestible aesthetics must be adhered to.

But beauty is narrowly defined in secular society too. There is, at present, a 400-plus billion dollar “beauty industry” aiming to “empower” individuals to attain higher levels of physical attractiveness and self-regard. Needless to say, this approach can be exhausting and, not infrequently, fruitless. Are “beautiful” people ever content with their looks? Not easily, as supermodel Emily Ratajkowski expressed in her memoir: “I’m always thinking…if only my nose was a little smaller, my whole life would be different.” When we approach beauty from a standpoint of control, it’s a mug’s game.

In this issue we look for the beauty in the ugly, and the ugly in the beauty. Gretchen Ronnevik writes about the truth of sad things; Michael Wright peers into the darkened vault of Thomas Kinkade’s most intimate paintings; Ross Blankenship praises poetry in the age of artificial intelligence; and Jane Anderson Grizzle investigates why everything that’s supposed to be “beautiful” looks the same. Other insights come from scholar Natalie Carnes, art historian Matthew J. Milliner, novelist Randy Boyagoda, and writer Joy Marie Clarkson.

This issue also features four interviews, with two-time National Book Critics Circle Award finalist Paul Elie; prolific poet Jeanne Murray Walker; Atlantic culture critic Sophie Gilbert; and art historian Aaron Rosen. We have fresh poems by Jeanne Murray Walker, Ryan Alvey, and Paul J. Pastor, plus new writing by Kathleen Norris and a long-awaited contribution by our copy editor extraordinaire, Ken Wilson. Sarah Condon offers new advice on postpartum bodies and in-law relations, and David Zahl connects our desire for beauty to our most fundamental need—the need to be loved.

Through it all, we find the truest, most beautiful thing we know: that grace falls on the undeserving. After all, you’re not loved because you’re beautiful, you’re beautiful because you’re loved.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ESSAYS

Pretty Hurts

GRETCHEN RONNEVIK

A Visit to the Precious Moments Chapel

MATTHEW J. MILLINER

Flat Earth

JANE ANDERSON GRIZZLE

Can Poetry Save Your Life?

ROSS BLANKENSHIP

Kind of Scary, I Guess?

RANDY BOYAGODA

The Call of Beauty

NATALIE CARNES

The Whole Picture

MICHAEL WRIGHT

London Calling

JOY MARIE CLARKSON

INTERVIEWS

JEANNE MURRAY WALKER

SOPHIE GILBERT

PAUL ELIE

AARON ROSEN

POETRY

Little Blessing for Subplots

Small Formal Treatise on Beauty

50th Birthday

JEANNE MURRAY WALKER

The Crystal Hand

By Dying Oak

PAUL J. PASTOR

Sleep Comes by Hearing

Holy Ground

RYAN ALVEY

LISTS & COLUMNS

The Confessional

ANONYMOUS

Dear Gracie…

SARAH CONDON

Finding Beauty in the Unexpected

KATHLEEN NORRIS

From the Glossary

On Our Bookshelf

Bible-Based Beauty Products

Running After Tops

KEN WILSON

SERMON

The Cheap Perfume Route

DAVID ZAHL

Visit our store to find this & other available issues!

THE BEAUTY PLAYLIST

Looking for more? Check out our online samples here.

SUBSCRIPTIONS

A four-issue subscription is $60. As our emphasis on grace might indicate, we’re terrible at hitting deadlines, but you can expect 2–3 issues per year. To subscribe to The Mockingbird, sign up here or become a monthly giver. All monthly donors to Mockingbird receive a complimentary subscription.

CONTACT

To send pitches, promotional copies, or interview requests, write to us via email at magazine@mbird.com.

You can also send mail directly to our office at:

Mockingbird

100 West Jefferson Street

Charlottesville, VA 22902