Without giving anything away, NBC’s The Good Place features six major characters, one of whom is Tahani al-Jamil: a tall, gorgeous philanthropist with an exclusive interest in herself. When asked to describe Tahani, her friend Eleanor rattles off the following, with affection: “self-obsessed socialite, ridiculous giraffe, absurd British aristocrat, narcissistic attention seeker.”

In Season 2, Tahani is tested: she must walk down a long hallway, past a series of doors behind which personalities like Prince Harry, Fergie, and Stephen Hawking are all talking about…her. She can’t resist; even in crisis, Tahani is Tahani. But keep watching. Visit her childhood, where her parents dismiss her as a disappointment, where it seems no one is talking about Tahani and everyone is talking about her sister. She spends her life (and her afterlife) desperately trying to establish her self as noteworthy, interesting, lovable—until the only person she cares for is herself.

I’m hesitant to diagnose this character, with any authority, as a capital-N Narcissist. As Kristin Dombek points out in The Selfishness of Others, ‘narcissism’ is a charged term which we deploy outside of clinical settings, at different times to convey different things. Generally speaking, though, the degree to which a person seems self-involved determines our nontechnical diagnosis of them.

I’m hesitant to diagnose this character, with any authority, as a capital-N Narcissist. As Kristin Dombek points out in The Selfishness of Others, ‘narcissism’ is a charged term which we deploy outside of clinical settings, at different times to convey different things. Generally speaking, though, the degree to which a person seems self-involved determines our nontechnical diagnosis of them.

Dombek contextualizes this more casual usage: “I suspect some of the things we condemn as narcissistic in others might be more accurately defined as how everyone has to perform—in capitalism, or online—doing things formerly considered vain, things we feel guilty or anxious about.” We live in a world that demands slick self-presentations, beauty, strength, confidence. Yet any time a person tries meet these demands by sharing, expressing, or performing…we smell narcissism. The regime du jour shifts. We condemn self-expression as “navel-gazing,” as contemptible self-absorption. Thus the rise and fall of the personal essay. Thus the abashed post-selfie grimace.

The journalist Brooke Lea Foster once argued that ‘narcissism’ has been an insecurity of every generation: “Consider the 1976 cover story of New York Magazine, in which Tom Wolfe declared the 70s ‘The Me Decade’” or “Time’s 2013 cover story ‘The Me, Me, Me Generation.’” It’s safe to say that wherever ‘me’ goes, condemnation follows. There is even an unspoken anxiety (ahem, narcissistic anxiety) about being narcissistic.

Such anxiety bears out mightily in Christian environments. I once heard in a Bible study, “Humility isn’t thinking less of yourself, it’s thinking less about yourself.”

This may be true. But having tried it for years, I now wonder, what if you can’t think less about yourself? Wouldn’t you, then, think less of yourself? And consequently, more about yourself?

Let’s try it. Don’t think about yourself.

Did it work?

None of this is intended to suggest that self-preoccupation is somehow virtuous or productive. It can be healing, for a while, to forget oneself, to lose oneself in a pleasant distraction. On a recent (distracting) trip through the YouTube wormhole, I came across a charming interview with Jennifer Lawrence. Faced with a rapid-fire series of questions, she pauses at one in particular. “Do you believe in the afterlife?”

“I don’t know,” she says, seeming surprised. “No. Leaning more towards no.” For a moment, she ruminates intensely, then continues, “I feel like it’s just a reaction to innate narcissism—that we just believe we can’t not exist.” It’s an especially compelling theory coming from Jennifer Lawrence. But you might have a hard time finding a child with a terminal illness who would say the same. I’d guess (and from personal experience) that anyone who suffers might see the afterlife less as a means of self-perpetuation and more as a vision of hope, a second chance.

In the end, it’s probably both. Our spiritual desire for a life after life may well be connected to self and suffering. In all of us, both exist: a self who suffers, and a self who longs to continue despite the certainty of death; a self who longs, period. For affirmation, justification, perpetuation, anything to quiet the dissonance, insecurity, and anxiety inside.

In his fantastic series on Christopher Lasch’s The Culture of Narcissim, Michael Nicholson describes how conspicuous self-absorption—as with Tahani—is often rooted in lack: “Pathological narcissism couples the outward expression of egocentricity and self-absorption with an actually weak sense of self, inner emptiness, and a constant need for external validation and gratification.” So what we write off as “narcissism” may really be attempts to overcome an inescapable lostness.

And who isn’t a lowercase-n narcissist, at least sometimes? Who wouldn’t be entranced (if momentarily) by their reflection in the water? As Walker Percy wondered: “Why is it that, when you are shown a group photograph in which you are present, you always (and probably covertly) seek yourself out? To see what you look like? Don’t you know what you look like?” It may at first seem that Percy is pointing out a universal self-centeredness; not exactly. Percy sees this outward narcissism as a sign of something deeper: of our wandering, and seeking. We are, as the title of the book says, Lost in the Cosmos.

*

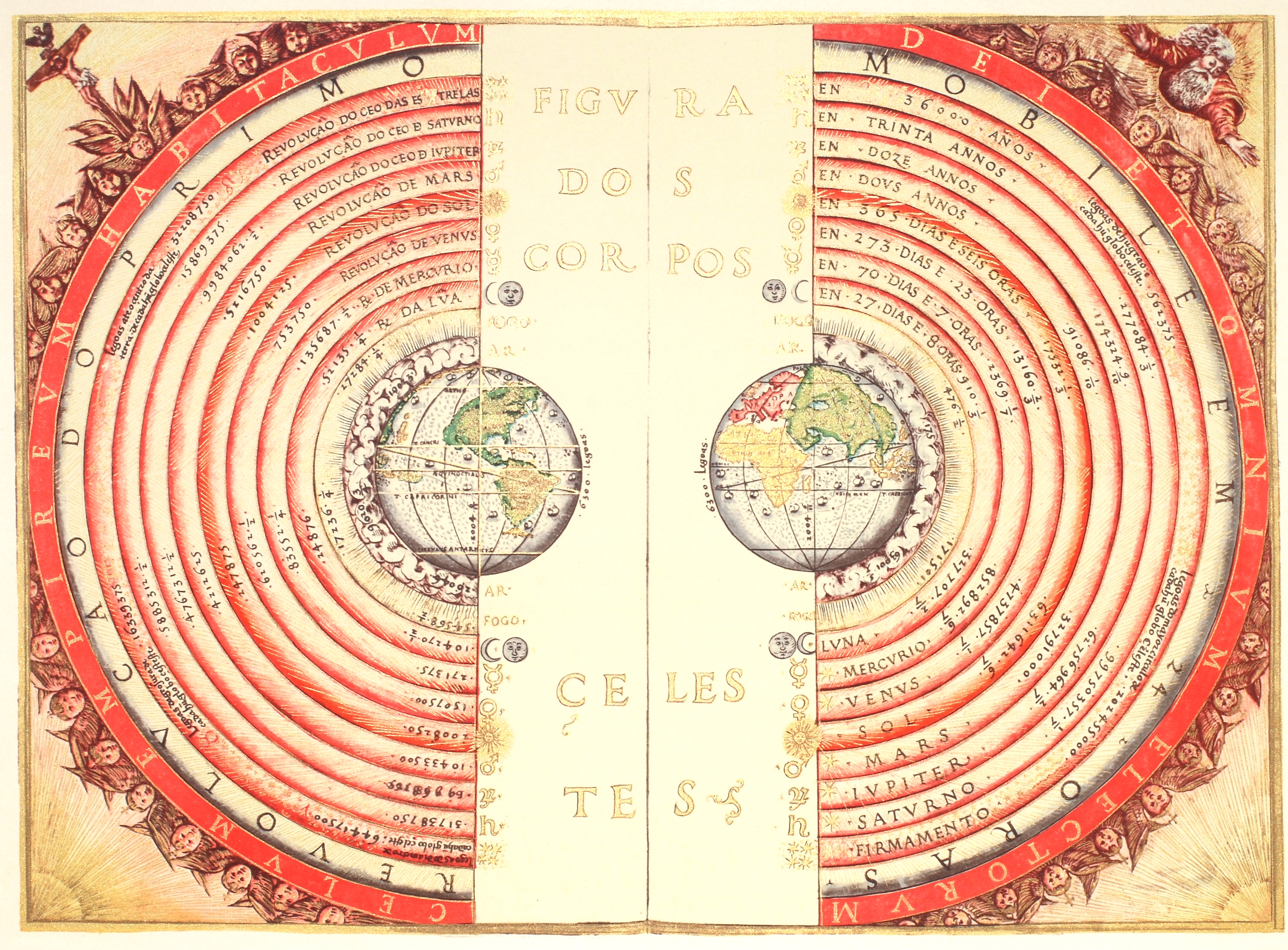

Recently I stumbled across the Netflix series Explained. With few exceptions, the episodes are interesting and easy to watch, and the opening credits are catchy (very important). It was their Astrology episode that inspired this soapbox. Did you know: every major ancient civilization developed some form of astrology? Part and parcel to astrology is geocentric theory, that everything revolves around the Earth, around us. Narcissistic, no? The star signs only make sense if Earth is the center of the solar system. But of course you know: it is not.

Even so, scores of people continue reading horoscopes, attending astrological conventions, and seeking predictions based on the positioning of the celestial bodies. From 2016 to 2017, astrology videos on YouTube increased in popularity by 62 percent; on Twitter, “engagement” with astrology increased by nearly 300 percent.

Perhaps astrology is simply “trending” and will leave us as quickly as it came—but perhaps a whole generation is lost in the cosmos and seeking answers wherever they can get them. Explained suggests that people who feel less “in control” of their lives are more willing to see themselves in horoscopes. In many ways, astrology is doing what religion once did, eliciting stability from the unknown. There is, however, a key difference, according to psychologist Stuart Vyse:

The great appeal of astrology even in the age of science, even among educated people, comes from the fact that it offers something that you can’t get easily in other places… It’s personal. Because you get your personal horoscope, and your personal chart. And, in that way, it may do something different than a traditional religion where you were one of a large flock.

In short, astrology caters to a narcissistic craving when traditional religion would not. Of old were commandments to be humble, to think less about ourselves, to do any number of righteous but impossible things so as to make ourselves worthy of an easily displeased god. Importantly, however, those imperatives remain even outside of church, when we impress the importance of understanding that we are not the center of the universe; and our longing to be is shameful.

Today, we believe everyone should stop navel-gazing. Weirdly, though, everyone has Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram. In social justice activism: we should think about solving society’s problems but keep quiet about our own. One of our age’s biggest narcissistic wounds is our repudiation of the humanities. The study of human experience, as told by personal histories, art, and expression: not worth the cost of tuition.

Astrology emphasizes the opposite. In astrology, Earth, humanity is once again the center of universe, unapologetically so. Your reading is tailored to you, mine to me. Every moment of your life is part of a larger puzzle, as dictated by celestial bodies, right down to the minute you were born.

Last week, a neighbor worked out my horoscope chart. We spent about half an hour reading detailed descriptions of my sun sign, my moon sign, my rising sign. The narcissist in me loved every minute. We determined that roughly 50 percent of my reading rang completely true; the other 50 percent, though, seemed off. To be fair, we didn’t know the exact time of my birth, which, my neighbor explained, could account for the inconsistencies in my reading. After all, the planets would have shifted between 12:00PM and 1:00PM. Did I buy that? I wasn’t sure. In the moment, it was enough of an excuse to keep me reading…about me.

I imagine that when it comes to astrology, a lot of people have this experience. Perhaps, having passed seventh grade science, you aren’t entirely convinced that distant balls of gas ordain your life, but you want personal answers anyway. You want a guide to life, one that’s for you, for today. That’s what I wanted, anyway. Then again, I am a Leo. Which also might explain why I take so much comfort in the following psalm, sent to me faithfully by my grandmother every August for my birthday:

O Lord, you have searched me and known me…

Even before a word is on my tongue,

O Lord, you know it completely.

You hem me in, behind and before,

and lay your hand upon me…Where can I go from your spirit?

Or where can I flee from your presence? […]

If I say, “Surely the darkness shall cover me,

and the light around me become night,”

even the darkness is not dark to you;

the night is as bright as the day,

for darkness is as light to you.

If I am to believe this psalm applies to my life, and I do, then I also believe God surrounds me, not unlike the celestial bodies, and knows every hair on my head, every thought that I have thought. Every day that I will live has been laid out by Him, fearfully, and wonderfully.

This fearful, wonderful God values weakness over strength, humility over pride. If the old saying is true—that humility isn’t thinking less of yourself, it’s thinking less about yourself—then I am led to one conclusion. Except by the grace of certain distractions, I am always thinking about me. Thankfully, so is God.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply