Back in 1998, my father wrote an unfashionable yet characteristically compelling little volume entitled The Protestant Face of Anglicanism. With the big anniversary finally here, it seemed like an ideal time to remind people of its existence (and merit)! Coincidentally, the book shares the title of PZ’s latest project, a tumblr devoted to, well, you guessed it. He’s provided us with a personal introduction to the project below, but first, a couple of zinging paragraphs from the final chapter of the book in question:

The Reformers saw the message of justification as a word of comfort, first and primarily, to the troubled conscience. The conscience, unable to convince itself of its worth, justification or inclusion within the circle of satisfying acceptance, was understood and actually felt to be the burdened Achilles’ heel of human consciousness in general. Luther had identified this exact point of stress in his breakthrough document of 1518, entitled “A Disputation Concerning the Investigation of Truth and the Comfort of Alarmed Consciences.” Luther understood from the beginning of his reforming work that the universally experienced problem of perceived unworthiness, or guilt in the deepest sense, had to be the problem to which religion, in order to be any good for us, must address itself. At the cutting edge of Christology that is denominated by the words justification by faith, Luther discerned the true potential for “wholesomeness” and “comfort” incipient within Christianity. Everything beside that was beside the point. The word of Jesus Christ had to strike home here, in the conscience, for it to be credible–as opposed to false promise, a pretty picture, an instructive story.

[The English Reformers, as demonstrated officially in the Articles and Homilies of the Church of England, adopted Luther’s insight concerning justification all across the line. William Tyndale’s debt to this insight became the debt owed by all English Protestants…]

Grace imputed to the human being creates the intrapsychic situation, the felt situation, in which we are unqualifiedly cherished and yet at the same time more aware than ever of our humanity, hence of our imperfections. The either/or of the full forgiveness of sin achieved on the cross results in the both/and of human experience as new creation. We are both fully new and terminally old, accepted and repentant, inflated by hope and ever deflated by our own self-knowledge. The situation becomes one of irrepressible confidence in God and the realistic measurement of our own weakness. Hope and realism, inextricably linked by the teaching of imputation, is the vantage point from which Christian experience is lived out.

Amen to that! And now, here’s PZ’s introduction/invitation to the new site:

“For almost 50 years — can scarcely believe it’s true — I have been collecting visual material related to the Protestant element in Episcopalianism/Anglicanism. As a boy I was schooled in Liberal Low-Church Episcopalianism, which was quietly paramount in the area where we lived. In fact, it was the only version of mainline church I knew.

Later, after a religious conversion, this interest became more personal.

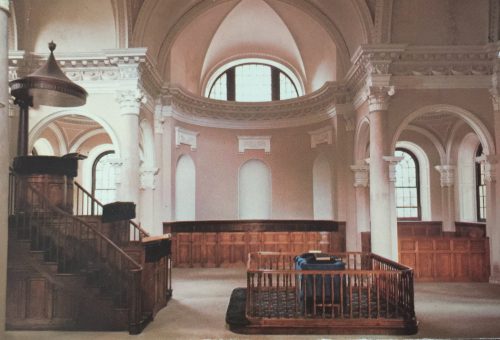

Beginning in early 1974, Mary and I clambered over dozens and dozens, and finally hundreds and hundreds of old churches, especially ones with Protestant patrimony in the architecture or fittings. We went up and down the Eastern Seaboard visiting old remote Episcopal Low Churches, odd survivals in an era of rapidly disseminating Liberal (Anglo-)Catholicism. After 1979, the once familiar Low-Church tradition in the Church went underground — at best. Actually, basically, this tradition disappeared.

Beginning in early 1974, Mary and I clambered over dozens and dozens, and finally hundreds and hundreds of old churches, especially ones with Protestant patrimony in the architecture or fittings. We went up and down the Eastern Seaboard visiting old remote Episcopal Low Churches, odd survivals in an era of rapidly disseminating Liberal (Anglo-)Catholicism. After 1979, the once familiar Low-Church tradition in the Church went underground — at best. Actually, basically, this tradition disappeared.

It did not disappear in the Church of England, however, for a bunch of reasons. And when we would get disheartened over here, we would travel over there!

My new Tumblr blog, entitled “The Protestant Face of Anglicanism” is a most personal attempt to bring together the materials Mary and I have collected: photos, postcards, guidebooks, out-of-print scholarly books, even movie stills, you name it — and “put them out there”. My plan is to post a photo or two each day, barring absences or depressed inspiration, with a caption underneath it that explains it.

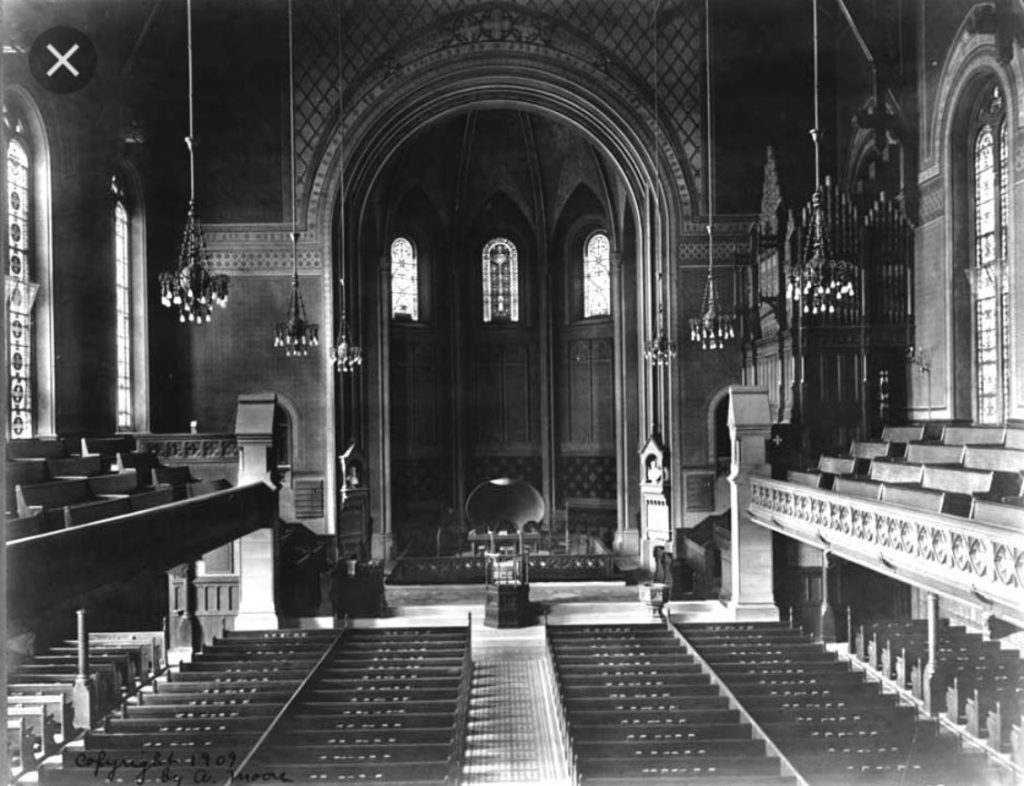

I am also interested in Protestant/Low-Church Anglicanism/Episcopalianism as it appears in popular culture. And it does. From ‘high brow’ sources such as Thomas Hardy’s “Tess of the d’urbervilles” and George Eliot’s “Scenes of Clerical Life, to more ‘popular’ sources, like “The Parent Trap” (1961) or “Mrs. Miniver” (1942), let alone beloved movies like “The Bishop’s Wife” (1947), traditional Low-Churchmanship is frequently encountered in our Anglo-American past. Then take a drop down Memory Lane — but it’s really the Center of Gospel Life for a whole section of New York City — the community of St. George’s Episcopal Church, Stuyvesant Square with Calvary Episcopal Church, Lower Park Avenue (pictured below, where Mockingbird’s annual New York conferences are held) — and you will see a modern echo of this movement. It is Balm in Gilead for the urban Now.

The Protestant Face of Anglicanism is not just history, in other words.

Now “Come with Me and Take a Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea” (Frankie Avalon, 1961). Or rather, as the twinkling Low-Church Rector of St. Nicholas, Toxteth in Liverpool, Daniel Bartlett, once told a skeptical Archbishop of Canterbury, who had asked him, ‘So, Bartlett, what does it feel like to stand out on the edge, the very edge of our Communion?’: ‘No, my Lord, not on the edge. But in the center, the very Center, of our Faith.'”

COMMENTS