The first Zahl I met was the youngest, Simeon. He was an undergrad in the college ministry where I volunteered. He invited me to come hear his father give a talk on his book The First Christian at the home of Peter Gomes in Cambridge, MA. That was the first time I met Paul. I didn’t understand a thing he said, but I bought his book, he graciously signed it, and that was that.

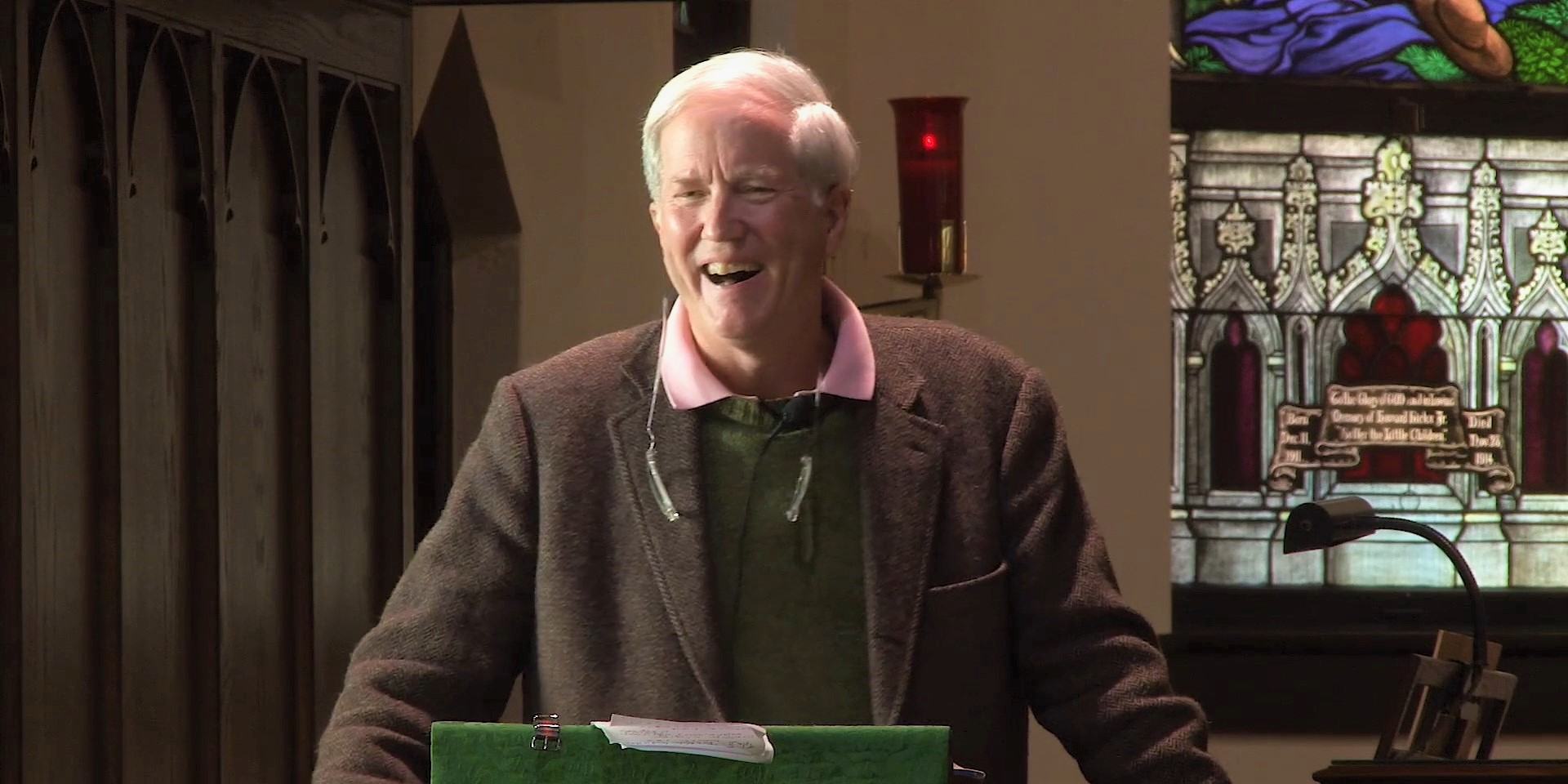

Three years later, I entered seminary at Trinity Episcopal School for Ministry in Ambridge, PA. Paul had just left the Cathedral in Birmingham, AL, to become the Dean. I would eventually take three classes from him, attend his early morning Thursday Bible study, and hear him give dozens of talks as part of the weekly Dean’s Hour.

The seminary was abuzz. Paul brought an emphasis on grace and a unique approach to ministry. Some loved it. Some were confused. Others were opposed. The result was a campus that was filled with theological conversation. People were animated. Discussions — whether in class, in the dining hall, or on front porches — were incredibly stimulating.

It was a time when we all felt theology truly mattered. What you actually thought about the nature of God as revealed in Jesus Christ — not what you said you thought, but what you actually believed deep down — really mattered. It mattered because it would inform your preaching and ministry for decades, and in your congregation it would either lift up or tear down. The same would be true for the preacher herself.

I personally was transformed through Paul’s ministry in those years. As Paul turns 70, I’ve taken some time to write down some of the many things I learned from him.

Let me begin with preaching. I would not be the preacher I am today without him. He is the single largest influence on my preaching, and it’s not even close. I came into seminary thinking sermons were one thing, and I left thinking they were something totally different.

I used to think the point of the sermon was, first, an intellectual one: to educate the hearers on the meaning of the entire passage. Then, the second point was a moral one: exhort them to adopt that understanding and its corresponding behavior. I (wrongly) thought that understanding more and more Bible would make people better Christians. (I should have listened to Jesus: “You study the scriptures because you think in them you will have eternal life …” Jn 5:9). Paul taught me that the point of the sermon is for the hearer to feel seen, as he or she is, and forgiven in the name of Christ. The sermon’s point is to shine the light of God’s love into the darkest place of the individual human life.

Here are the other things Paul taught me about preaching:

– I learned how to be funny in the pulpit. Like, really funny. Previously, I had only seen pastors deliver lame pastor jokes: “An avid golfer died and met St. Peter at the Pearly Gates …” Paul was a master at irony, asides, and the “benign violation”: saying the unexpected, breaking the rules of what one is supposed to sound like in the pulpit. Paul would say things like, “No one listens to the first two minutes of a sermon,” while he was in the first two minutes of his sermon. (He was absolutely right, by the way.) I had never heard anyone use self-referential irony like that. Humor largely comes from saying true things that one is not supposed to say out loud. Paul told the truth. That is to say, he was hilarious.

– I learned it was OK to talk about the sermon in the sermon. Paul taught me to do the Gaffigan-esque thing where one mentions, in a sermon, when a joke falls flat or an idea doesn’t land. To be a third-person observer of oneself while preaching, and to be aware of how the message is being received — and to name what is happening (“Well, that was funny in my head”). It is hugely anxiety-relieving for the congregation, when a sermon is bombing, for the preacher to acknowledge, with humor and humility, what is happening. When the pastor names the awkwardness, the congregation doesn’t have to carry that burden itself.

– I learned how to have a conversational preaching style — and near the end of the sermon, to ask, “What about you? Where does this connect with you?” In doing so, it became more than conversational. It was deeply existentially connected to every hearer in a profound way.

– I learned how to use a sermon illustration, and the power it has. Another thing Paul said, which people hated, but was totally true, is that the illustration is more important than the exegesis. I mean, exegete correctly, by all means. But no one will remember that. They will remember, however, the illustration that made them feel seen.

– Mentioning things like broken family relationships was a key Zahl thing. And Paul made them very specific: Your first husband, your second wife, your adult son, your middle child. This really connected with people.

– Paul showed me how important psychology is, and how crucial it is to talk about people’s pasts and their inner lives — what is actually on their minds. One quote I remember him saying, and I use this all the time: “You would be amazed at what people are actually thinking about. It’s usually one thing, it’s all they think about, and no one knows.” Man, this is so true. And it’s preaching gold. People feel deeply understood.

– Paul freed me from feeling like I had to explain everything in the text. A sermon is a sermon, not a Bible study. Paul, by his example, gave me permission to pick one word, one phrase, one verse, and just talk about that.

– Paul taught me that short sermons are better, generally. “The Gospel is a short word,” he would say. He would quote Luther’s hymn, “A Mighty Fortress is Our God”: “One little word shall fell him.”

– Paul taught me to begin out of left field. And how pop culture references surprise and wake up a dazed congregation. Be unexpected.

– Paul taught me to begin out of left field. And how pop culture references surprise and wake up a dazed congregation. Be unexpected.

– On that note, Paul opened the world to me in showing me it was OK (even a good idea) to use pop culture, secular culture, in preaching (and writing). I simply hadn’t felt the freedom to do so before. Particularly around music. I love music, so this was huge for me. And it absolutely connects with people.

– Paul was simultaneously low-brow and an academic of the highest credentials. He made me feel like I could reference both Blondie and von Harnack in a sermon. He used French phrases without apology. I now do that with Spanish. Paul showed me I was allowed to bring my education, my background, myself, into the pulpit.

– Paul taught me that ending a sermon with an application never works. I have never done it.

Moving on from preaching to general pastoral ministry:

– Paul taught me the power of a hand-written note. And to use weird postcards — much more fun and memorable — than fancy stationery. I have used these since the beginning of my ordained ministry and people hold onto them forever.

– Paul taught me about AA and had his students read the Big Book. This has been HUGE. It was so personally important for me. Plus, I reference it in sermons and counseling all the time. It never fails to connect. Also, it sends out a “dog whistle” to people in recovery that this parish is a safe place for them. There are more people in the pews who are in recovery than most pastors realize.

– Paul taught me the incredible pastoral power of remembering people’s names. That is, actually caring about them. So many people have joined the church where I serve simply because I remembered their name the second time they came.

– A narrative aside: At the seminary, I noticed Dean Zahl was incredible at remembering names. I asked him how he did it. What was the mnemonic device? What was the trick? He replied instantly: There was no trick. One just had to care about people. He said this with total sincerity, without an ounce of rebuke. Inside, I thought, “Well, crap.” Because I wanted a hack for ministry success. But Paul reminded me that “If I have not love …” He was so right. It taught me from then on, when meeting people in church, I had to get out my self-absorbed head for a second and say to myself, “Now this is a person. Care about them. Actually pay attention when they tell you their name.”

– Paul taught me how to react when challenged publicly. I saw this happen at the seminary all the time in lectures. Paul was totally non-defensive and did not react. He would just say something like, “Well thank you, So-and-so. I receive that and thank you for that point.” Sometimes he would say, “That’s interesting. Say more about that.” He was very chill about that. And it was brilliant.

– Paul taught me the importance of appropriate clerical apparel. I didn’t even know what choir dress was before meeting Paul. I now wear cassock, surplice, and preaching tabs every Sunday, thanks to Paul. And I do it not for aesthetics, but for the underlying theological and liturgical significance. When not in a service, I wear a suit (or blazer) and collar or a suit and tie. People feel honored and respected, and it matters.

– Paul taught me the importance of appropriate clerical apparel. I didn’t even know what choir dress was before meeting Paul. I now wear cassock, surplice, and preaching tabs every Sunday, thanks to Paul. And I do it not for aesthetics, but for the underlying theological and liturgical significance. When not in a service, I wear a suit (or blazer) and collar or a suit and tie. People feel honored and respected, and it matters.

– I am self-consciously a Protestant, and I am aware of the Protestant roots of Anglicanism.

– I love how, when he gave a talk, during the Q & A, he would always ask Mary if he had left something out. It was so touching and humble, and showed what a pair they were in ministry.

– I learned how important it was to have parties at the rector’s house, to make it nice, and to make people feel special. At the annual Christmas party, he stood outside the house in that red waistcoat, greeting people as they arrived. I’m sure he’d done the same thing at the Advent and everywhere else. It made such an impression on me. When he left the school, he gave away a bunch of clothes. They were on a rack in the hallway outside the school’s dining hall. I ended up with several of his suits — and the holy red vest. I wear it every year at our Christmas party for staff and vestry. And I wear it to church on Christmas Eve. It is one of my most treasured possessions. It reminds me of Christian hospitality.

– I learned that humor and playfulness can make a church feel human, warm, and welcoming. I loved his aliens and weird posters at the seminary. It taught me something I have carried into my ministry: Play matters.

– Paul taught me to be mindful and aware of what’s going on in my own life and mind. To pay attention to what a passage is saying to me. To what reaction a parishioner is provoking in me. Paul taught me to be aware of my blind spots.

Bottom line:

– Pathos (which is based in listening) and humor are the key to effective pastoral ministry and preaching. Paul showed me this, and now thirteen years of ordained ministry have borne this out.

The impact of all this has been profound. In my current ministry in Waco, TX, St. Alban’s average Sunday attendance has grown from 150 to 350 in eight years. We originally had two Sunday services; we now have four. We completed a $6 million campaign to build a new Parish Hall and Welcome Center. We are now in a $3.5 million campaign to renovate the church building and install a new organ. (I only mention the money because it shows how grace births generosity; when people are sincerely loved, there’s a desire to give.) We have members who drive forty-five minutes, or even an hour, to come to church. We have become a Christ-centered place of grace, and people are flocking to the parish. The staff like each other and enjoy working together. We have fun. People’s lives are deeply touched through our shared ministry. Clergy from around the country call me seeking advice and counsel.

I know that none of this would have happened without Paul Zahl teaching me, by explicit instruction and implicit example, how to be a preacher and pastor. I cannot overstate his impact on me personally, or my ministry. Thanks be to God. And happy birthday, Paul.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply