The events at the Capitol on January 6 were deeply disturbing, to say the least. Among much else, they have been described as an “Attack Against Multicultural Democracy,” “A Christian Insurrection,” “White Supremacy in Action,” and “The End of the Road for American Exceptionalism.” As is his wont, Dan Rather summarized how many of us felt a few days later:

I agree: “We must cultivate hope while demanding justice.” But as we now mark another Martin Luther King, Jr., Day and approach the inauguration of a new president, I find myself wondering, like the psalmist: Where exactly does our hope come from? Where do we find the hope that we can indeed move forward together in this time — towards something resembling “justice for all” — when there is so much evidence to the contrary?

The great moral leaders of the past are those who neither ignored the popular struggles of their day nor conformed to the dominant tribal modes of addressing them, but who instead showed people how to move forward in hope — how to maintain conviction without nurturing hatred, how to seek justice without turning to violence, how to act with moral urgency without descending into desperation, extremism, or grasping at power. In other words, they are the ones who teach us how to practice the grace of the cross in the midst of the world’s grave conflicts.

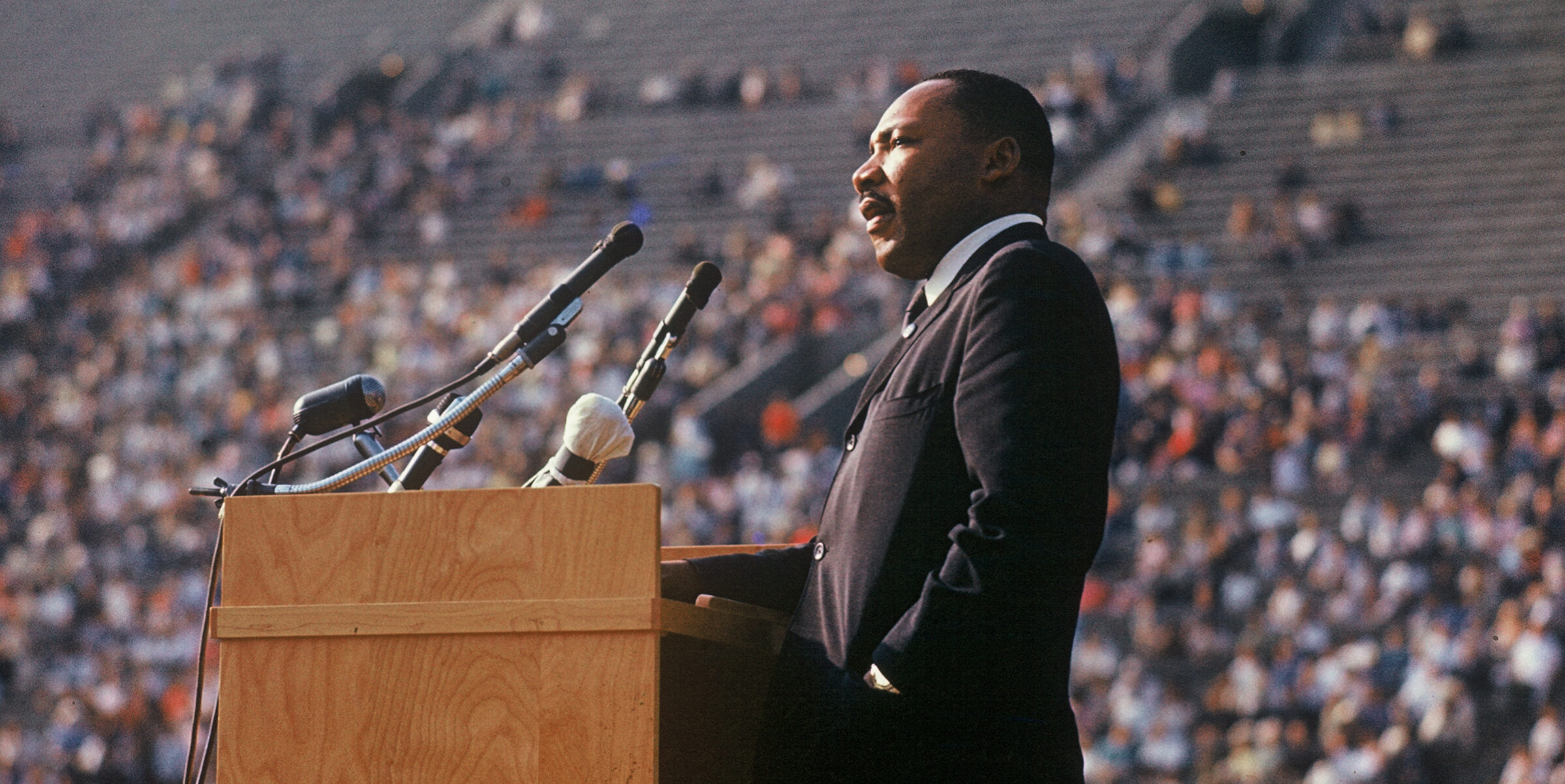

One of those great moral leaders, of course, was Dr. King. It’s almost a cliché at this point: King showed us again and again how to confront even the most intractable injustice with love rather than hate, with hope rather than despair — the hope that never gives up on our fellow human beings, even when they are so clearly overcome with the power of darkness.

But King’s journey as a leader was never a smooth one, and by the time of his assassination in 1968, his influence had been waning for years. Following the high-water mark of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965, the movement he’d helped to build and lead had splintered into many discordant factions. Much of the reformist optimism and momentum of the early ’60s had evaporated. Ever more sectarian violence was erupting in the streets. The war in Vietnam raged — and with it, a torrid culture war back home — even as many of LBJ’s Great Society initiatives withered. In the late ’60s, America was unraveling. It was a scary time.

Ours too is a scary time. As we reflect on King’s legacy in our own fraught context, I think it’s thus worth looking back not so much to those famous speeches and writings from his earlier career — long tinged with a kind of revisionist post-racial triumphalism — but to one of his most challenging and incendiary later speeches, the “Beyond Vietnam” speech, delivered from the pulpit of Riverside Church in New York, one year to the day before his death.

It’s a long, dense speech, and one of King’s most sweeping, covering issues from militarism and the Cold War to poverty and the ravages of materialism. But his first priority was to speak with clarity against the Vietnam War — despite the likely consequences, and despite the moral fog that pervaded the period. As he explains, “[W]hen the issues at hand seem as perplexing as they often do in the case of this dreadful conflict, we are always on the verge of being mesmerized by uncertainty; but we must move on.” King thus spends much of the speech decrying the Vietnam War and defending himself against those who’d have him stay in a Civil Rights silo.

But then, as was his style, King pivots towards a rousing climax — a broader vision for society that goes “beyond Vietnam” and gets at the roots of many of the world’s challenges, a vision as relevant today as ever. It is, in a sense, another iteration of the dream of a society transfigured by love, of the Beloved Community. King unfurls his dream using, in this case, the concept of a “true revolution of values” as a refrain. Here’s a taste:

[W]e as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin the shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights, are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.

A true revolution of values will soon cause us to question the fairness and justice of many of our past and present policies. On the one hand, we are called to play the Good Samaritan on life’s roadside, but that will be only an initial act. […] True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar. It comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring.

In riveting fashion, King goes on to describe how this “revolution of values” will also compel us to confront economic inequality, militarism, and much else, contending that such a “positive” approach is “our best defense” against the evils we face. “Let us not,” he charges, “join those who shout war […] but rather [engage] in a positive thrust for democracy.”

Ultimately, King crescendos into an appeal for the kind of love that he argues must be at the root of any such “revolution.” “In the final analysis,” he intones, “our loyalties must become ecumenical rather than sectional.” He continues:

This call for a worldwide fellowship […] is in reality a call for an all-embracing and unconditional love […] We can no longer afford to worship the god of hate or bow before the altar of retaliation. The oceans of history are made turbulent by the ever-rising tides of hate. And history is cluttered with the wreckage of nations and individuals that pursued this self-defeating path of hate. As Arnold Toynbee says: “Love is the ultimate force that makes for the saving choice of life and good against the damning choice of death and evil. Therefore the first hope in our inventory must be the hope that love is going to have the last word.”

To me, that is rich, convicting language. When I look out on the hateful, violent, polarized landscape of American society today — “a society gone mad on war,” as King calls it — I find myself agreeing with him: We desperately need a “revolution of values,” one rooted in the “hope that love is going to have the last word.” The events of January 6 are merely symptoms of underlying disease. In this context, King’s words fill me with moral urgency.

But there’s also something missing for me. As inspiring as his vision is, it’s insanely idealistic. It’s about as simultaneously inspiring and alienating as the Sermon on the Mount — a beautiful vision, but an impossibly demanding one. How can we ever hope to carry it out? Where does the will and strength to love our enemies come from? If we don’t experience the spirit and the hope that lies beneath it, such a dream will surely leave us more deflated than inspired.

For King, any progress towards the Beloved Community, however unlikely that can seem, is possible only because we are beloved by God. His hope was inseparable from his Christian faith. But that was as often implicit as explicit. So perhaps we need to make it explicit. As King put it to his detractors early on in the Riverside speech, “Have they forgotten that my ministry is in obedience to the One who loved his enemies so fully that he died for them?”

Where, therefore, does our hope come from? It begins in the mercy of the cross — in the knowledge that we are all both desperately in need of forgiveness and offered it freely through the self-emptying love of God in Jesus Christ. That’s the starting point. That’s the crack in history that opens up the possibility of brotherly love — of loving our enemies — and its structural cousin, justice.

Yet, it must be said, as the events of January 6 starkly illustrated: The meaning of Jesus and his cross are hardly self-evident. The Capitol riot, after all, had a well-documented religious impetus and fervor. Many wore crosses, recited Bible verses, or spouted religious slogans. With the nation watching, those zealots co-opted the language and symbols of Christianity.

Like many, I looked on and wondered to myself: What does the cross mean to them? For some Christians, it seems to be more a symbol of self-righteousness and tribal affinity than of God-righteousness and universal communion, a source of hate more than love. Thomas Merton memorably highlighted this distinction in New Seeds of Contemplation:

Strong hate, the hate that takes joy in hating, is strong because it does not believe itself to be unworthy and alone. It feels the support of a justifying God, of an idol of war, an avenging and destroying spirit. From such blood-drinking gods the human race was once liberated […] by the death of a God Who delivered Himself to the Cross […]. In conquering death He opened their eyes to the reality of a love which asks no questions about worthiness, a love which overcomes hatred and destroys death. But men have now come to reject this divine revelation of pardon, and they are consequently returning to the old war gods […] To serve the hate-gods, one has only to be blinded by collective passion. To serve the God of Love one must be free, one must face the terrible responsibility of the decision to love in spite of all unworthiness whether in oneself or in one’s neighbor.

Self-righteous, religiously-inspired hatred, rather than the reflected love of Christ, was on full display at the Capitol that dark Wednesday in January. Buildings were vandalized. Politicians fled in fear. People died. There must be consequences. But it would be a mistake for the rest of us to suppose that we are somehow above any such hatred or “collective passion.”

Though he only occasionally spelled it out, King understood where hope comes from, that the possibility of loving neighbors and enemies alike is rooted in mercy — the mercy of the cross. There is no hope for progress if we continue to divide the world between the beautiful and the damned, between those on the “right side of history” and the wrong. That way of thinking has been tried and found wanting, ad nauseam. Jesus showed us that we are all on the wrong side of history, that there can be no justice without mercy first. In making himself an atonement for the sins of the world, he opened up a way for us to move forward, together, towards reconciliation. Here’s Merton again:

The beginning of the fight against hatred, the basic Christian answer to hatred, is not the commandment to love, but what must necessarily come before in order to make the commandment bearable and comprehensible. It is a prior commandment, to believe. The root of Christian love is not the will to love, but the faith that one is loved. The faith that one is loved by God. That faith that one is loved by God although unworthy — or, rather, irrespective of one’s worth!

That, friends, is the meaning of Jesus and his cross, the hope that unites us and that needs cultivating during this time. Our quest for justice, for a “true revolution of values,” begins there. As Paul put it so succinctly, “God was in Christ, reconciling the world unto himself, not imputing their trespasses unto them; and hath committed unto us the word of reconciliation.”

COMMENTS

2 responses to “MLK’s “True Revolution of Values” Begins with the Mercy of the Cross”

Leave a Reply

THIS is amazing.

Believing his love for us – the unworthy us – de-weaponizes our Christian faith and our self-righteous ideologies.

I’ve passed this on to all of my family and friends. Henri Nouwen and George MacDonald are thrilled as well. May we all know how beloved we are.