This post comes to us from Jason Micheli:

When it comes to music, I’m no David Zahl, but, having once DJ’d for a rock station and — once that station went caput — having absconded with most of their music collection (#lowanthropology), I do rate as a lower level of nerd. As an aficionado, I insist upon two general objections when it comes to music. First, I believe the orchestral backing of a full symphony is nearly always a rotten ostentation to a rock song unless, of course, you’re Axl Rose. Second, I take it as self-evident that the intrusion of whisper-talking into the middle of a song is a deadly, distracting indulgence. During Ordinary Time, Madonna’s “Justify My Love” is perhaps the worst example of whisper-talking ruining an otherwise acceptable single while every Advent season — at least in the manner in which it is performed by many church soloists — it is surely Mark Lowry’s 1984 carol, “Mary, Did You Know?”

Much like with Van Morrison’s hit love song, “Have I Told You Lately That I Love You?” the implied answer should be obvious. No, Mary did not know the way in which her “Yes” to God was also, as Karl Barth says, the beginning of God’s final, once-for-all “No” to sinful humanity.

While Mark does not give us a nativity story, the beginning of his Gospel nevertheless provides scripture’s clearest answer to Mark Lowry’s question. Having emerged from the wilderness, Jesus inaugurates his ministry by healing the sick and exorcising demons, forgiving sins and declaring himself the Lord of the Sabbath. When his mother and brothers hear this “good” news, they respond by seeking out heaven’s perfect Lamb in order “to seize him, for they were saying, ‘He is out of his mind'” (Mk 3:21). Mark uses the same word, to seize (κρατῆσαι), that the Gospels later use to describe the arrest of Jesus. They want to take him, Mary’s baby boy, into custody; that is, they’re staging the first-century equivalent of an intervention.

Mary fears her baby boy is crazy.

This provides the occasion for Jesus to ask the crowds, “Who are my mother and my brothers? Whoever does the will of God, he is my brother and sister and mother.” For all the grief Peter suffers at the hands of lectionary preachers for not wanting a crucified messiah (“Get behind me, Satan!”), we neglect to notice how Mary’s response to the annunciation reflects the exact same biblical expectations for what constitutes a messiah as all the others who eventually abandon Jesus as an obviously accursed pretender.

Mary, clearly, knows her Bible, sampling as she does from Hannah’s song in 1 Samuel, but this does not mean Mary knows the way in which those biblical promises will be kept by God to establish her baby boy as “the Son of the Most High.” In his newest book, Kavin Rowe argues that “Christianity is still so much here with us that it is utterly familiar and has receded from us so far that we do not know what it is. This is not a step-wise process — here, then not here — but a simultaneous reality. Christianity is at one and the same time here and gone, familiar and forgotten. This is the world in which we live.” We forget, Rowe reminds us, the extent to which the Gospel constituted a surprise.

Mary, clearly, knows her Bible, sampling as she does from Hannah’s song in 1 Samuel, but this does not mean Mary knows the way in which those biblical promises will be kept by God to establish her baby boy as “the Son of the Most High.” In his newest book, Kavin Rowe argues that “Christianity is still so much here with us that it is utterly familiar and has receded from us so far that we do not know what it is. This is not a step-wise process — here, then not here — but a simultaneous reality. Christianity is at one and the same time here and gone, familiar and forgotten. This is the world in which we live.” We forget, Rowe reminds us, the extent to which the Gospel constituted a surprise.

Christianity’s surprise is inversely related to the degree and detail of messianic expectation in first-century Israel, especially in the region of Galilee. Messiah was a title onto which long-suffering Jews projected a variety of desires and presumptions, and no composite picture existed for a proper messiah. However, as the Gospels make clear, if there was any consensus about what comprised a messiah, it was that God’s messiah certainly would not suffer a shameful death that God’s own Law distinguished as a godforsaken death. This aversion to the cross reflects a correlative consensus expectation.

The messiah is a political figure.

Clearly, both the annunciation from Gabriel and Mary’s response to it reflect this widespread expectation, that Mary’s baby boy would grow up not “to make her new,” as Mark Lowry’s song says, but to establish a political regime. The disciples bring swords with them to Gethsemane because this is the kind of messiahship they expected of him. They — along with the rest of the Palm Sunday crowd — flee from him the next day because a crucified messiah is a failed messiah. And a failed messiah is, by definition, not the messiah.

“Keeping [these political expectations] in mind,” Rowe notes, “allows us to hear Mary’s hope in the Magnificat on a more mundane level: the Messiah will come as a political figure whose work and victory will involve throwing down the foreign overlords and exalting the Jewish people.” These expectations follow Jesus all the way to Good Friday, and John the Baptist, whose language “betokens a messianic revolution,” prepares the way. Indeed, the unexpressed — because it’s assumed — presupposition of the entire Passion story is that the messiah would be a political revolutionary who will liberate captive Israel. “In the time of the Gospels’ story-world,” Rowe writes, “Jesus’s words would have been heard as earthly political statements marking the cost of messianic upheaval and battle.”

Easter upends this story-world (which is also our world) where weakness is the opposite of power, sin is punished, forgiveness is costly, righteousness is earned, love is a two-way transaction, and death has the last word. The surprise of Easter forced upon God’s people a new hermeneutic by which to read scripture. When the Risen Jesus encounters the two despondent disciples on the road to Emmaus, he gives them a Bible study: “beginning with Moses and all the prophets, he interpreted to them the things about himself in all the scriptures.” Jesus does likewise with the eleven disciples just before his ascension. As Kavin Rowe says of these post-Easter Bible studies, “When you need an exegetical course from Jesus, you know that you do not know what you need to know.”

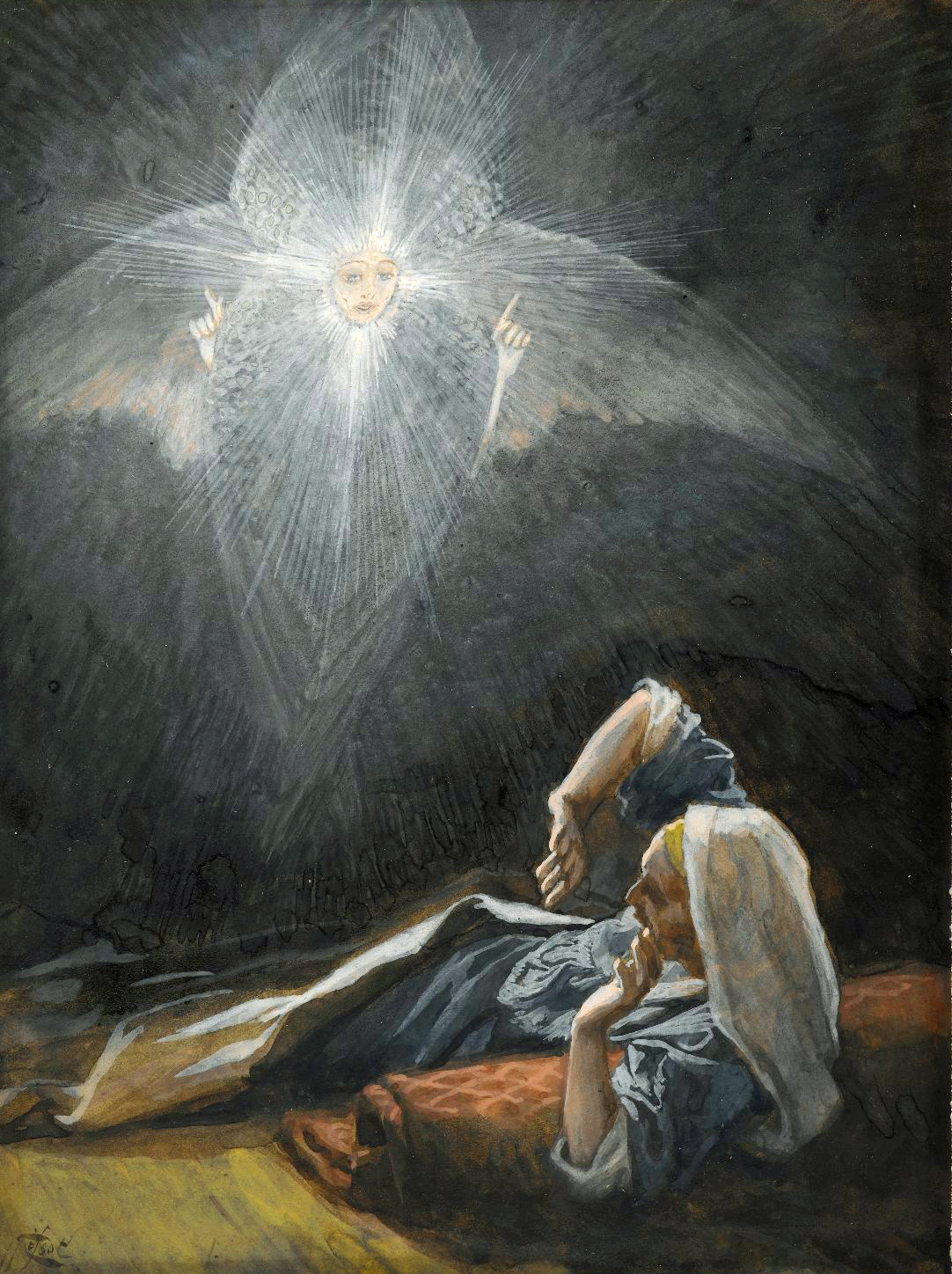

Despite the ubiquity of Mark Lowry’s carol, Mary did not know. Prior to Easter, Mary could not have known that she did not know what she needed to know. As both the first recipient of the angel’s news and the first proclaimer of it, Mary is thus the first person caught up in the surprise that hangs above her son’s thorn-crowned head: “This is the King of the Jews.” Mary is no different than any of us; in that, she cannot know the sign above her boy’s head is true prior to God’s raising him from the dead.

The lyrics to “Mary, Did You Know?” evolved from a series of questions that Mark Lowry scripted for a Christmas program at his church. “I just tried to put into words the unfathomable,” Mark Lowry explained. “I started thinking of the questions I would have for her if I were to sit down & have coffee with Mary. You know, ‘What was it like raising God?’ ‘What did you know?’ ‘What didn’t you know?’” Lowry starts with the ineffable way in which Mary is different from all of us. But Karl Barth, in his lectures on the Apostles’ Creed, Dogmatics in Outline, emphasizes Mary’s similarity to us. “We must not think of making a merit of this handmaid’s existence,” Barth lectured, “nor attempt once more to ascribe a power to this creature.”

Barth’s point is that Mary enters the creed as the first disciple. And as the first disciple, Mary is the first to discover what all disciples eventually realize; namely, that the messiah we expect (and want) is not the messiah we get, that a revolution premised on forgiving and even dying for your enemies does indeed fit you for a rubber room, and that, though the Law is written on our hearts (and all around us), grace comes so unnaturally that we require a post-Easter exegetical course from her Risen Son.

St. Luke reports in the Book of Acts that Mary was among those believers who constituted the Church in Jerusalem at Pentecost. Having gotten his messiahship all wrong at his nativity, having chalked him up as “out of his mind” at the beginning of his ministry, and having watched him suffer what her own scriptural interpretation told her was a death accursed by God, after Easter Mary was among the believers in Jerusalem worshipping her baby boy as the Messiah and waiting on the arrival of his promised Spirit. In other words, while Mary did not know what Mark Lowry thinks Mary knew, we know that Mary is among the first people to know the grace God makes flesh in her Son.

COMMENTS

One response to “Mary Didn’t Know”

Leave a Reply

I think the best thing we can take from Mary’s errors and assumptions about who her child was and what he would do is to see that we are so like her. The benefit of hindsight, suggested in every question of Lowry’s song, offers us the possibility that we “know” what Mary couldn’t know. But even with the benefit of the Gospels, the Epistles and Revelation, and 2000 years of observation there is little to suggest we know much at all about what Jesus is up to.

When we look around today, how often do we think Jesus and his wacky Holy Spirit might be off their game. He uses the disreputable and unlikeable. Jesus fails to fix the thing we demand he fix. He works through paths and plans we can’t fathom. And we are tempted to incarnate Christ into our agendas in response. We’re so like our mother. It must be hereditary