Teacher, is it lawful to pay taxes to Caesar or not?

Two hundred years before they posed this question to Jesus, Israel suffered under a different empire, a Greek one. And during that time, there was a guerrilla leader named Judas Maccabeus. He was known as the Sledgehammer. The Sledgehammer’s father had commissioned him to “avenge the wrong done by our enemies and to” — pay attention — “pay back to the Gentiles what they deserve.”

So Judas the Sledgehammer rode into Jerusalem with an army of followers to a king’s welcome. He promised to bring a new kingdom. He symbolically cleansed Gentiles out of the Temple, and he told his followers not to pay taxes to their oppressors.

Around 160 BCE, Judas the Sledgehammer got rid of the Greek Kingdom only to turn around and sign a treaty with Rome. The Sledgehammer traded one kingdom for another just like it. But not before he became the prototype for the kind of Messiah Israel expected.

When Jesus was just a kindergartner, another Judas, this one named after that first Sledgehammer, Judas the Galilean — he called on Jews to refuse paying the Roman head tax. With an armed band Judas the Galilean rode into Jerusalem to shouts of hosanna. Judas the Galilean cleansed the Temple. And then he declared that he was going to bring a new kingdom with God as their king. Judas the Galilean was executed by Rome.

Perhaps you can sense then what’s at stake when Jesus throws his Temple tantrum and when the Pharisees ask Jesus about paying taxes to Caesar. The only thing left for Jesus the Sledgehammer to do is to declare a revolution, to stand up to injustice, to deliver the oppressed, to cast down the principalities and powers from their thrones.

To take up the sword. That’s why the Pharisees and Herodians trap Jesus with a question about this tax. “Jesus, do you want a revolution or not?” That’s the real question. “Come down off the fence, Jesus. Which side are you on, Jesus?”

And Jesus responds, “Why are you putting me” — the LORD your God — “to the test?”

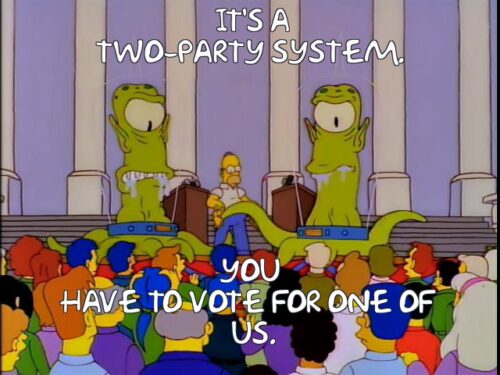

Politics makes for a strange bedfellow. The Pharisees and the Herodians were the two political parties of Jesus’ day. The Sadducees were theological opponents of Jesus. But the Pharisees and the Herodians were first-century political parties, who, despite their differences, discovered unity in their common opposition to Jesus. They were the Left and the Right political options. And instead of Donkeys and Pachyderms, you can think Swords and Sledgehammers.

The Herodians were the party that supported the current administration. They thought the administration was restoring Israel’s greatness. Rome, after all, had brought roads, clean water, sanitation. And even if it had taken a sword, Rome had also brought stability to the tinderbox called Israel. The last thing the Herodians wanted was a revolution, and if Jesus says that’s what he’s bringing, they’ll march straight off to Pilate and turn him in.

On the other hand, the Pharisees were the party that despised the current administration. It’s worth noting, for instance, that the Pharisee Zadok joined in with the failed revolution of Judas the Galilean. The Pharisees were something of a resistance movement. The Pharisees were Bible-believing observers of God’s commandments. They believed a coin with Caesar’s image and Son of God printed on it was just one example of how the administration forced people of faith to compromise their convictions.

The Pharisees wanted regime change. They wanted another Sledgehammer. They wanted a grass-roots righteous revolution. They just didn’t want it being brought by a third-party like Jesus, who’d made a habit of pushing their polling numbers down.

And so, if Jesus says he’s not bringing a revolution, the Pharisees will get what they want because all of his followers will think Jesus wasn’t really serious about this “Kingdom of God” rhetoric. They’ll write him off and walk away. That’s the trap. If Jesus says no, it will mean his death. If Jesus says yes, it will mean the death of his movement.

Which is it going to be, Jesus? The Sword or the Sledgehammer? Which party do you belong to? You’ve got to choose one or the other. Check the box, Jesus. What are your politics Jesus?

Jesus asks for the coin. And then he asks the two political parties: “Whose image is on this?”

Pretending not to recognize Caesar’s face on the coin, Jesus says, “Give to Caesar what is Caesar’s, but give to God what is God’s.” But it’s not that simple or clear, because the word Jesus uses for “give” isn’t the same word the two parties used when they asked their question.

When the Pharisees and Herodians asked their question, they’d used a word that means “to present a gift.” But when Jesus replies to their question, he changes the word. Instead Jesus uses the very same word Judas the Sledgehammer had used 200 years earlier. Jesus says: “Pay back to Caesar what he deserves and pay back to God what God deserves.”

His answer is ambivalent. What does a tyrant deserve? His money? Sure, it’s got his picture on it. He paid for it. Give it back to him. But what else does Caesar deserve? Resistance? You bet.

And what does God deserve? Everything. Like a good press secretary, Jesus refuses the premise of their question.

The Pharisees and the Herodians assume a two-party system. They assume it’s a choice between the kingdom they have now and another kingdom not too different, just of a different hue. They assume the only choice is between the Sledgehammer and the Sword.

But like a good politician, Jesus refuses their either/or premise. He won’t be put in one of their boxes. He won’t choose sides. Jesus refuses to accept their premise. His movement is about defeating his opponents by dying for them, and that qualifies all our politics.

As happened four years ago, it’s often said that this is the most important election of our lifetimes, and perhaps hindsight will bear it out. But magnifying the stakes this way is dangerous habit for self-justifying sinners whose hearts are idol factories and whose wills are bound.

This poses a serious spiritual problem. As a preacher I seldom dole out shoulds or oughts, but here’s an exhortation, a simple nonpartisan election season prescription: don’t do to Jesus what Jesus wouldn’t do to himself. Don’t box Jesus in and make Jesus choose sides. Don’t put a sword or a sledgehammer, an elephant or a donkey, in Jesus’ hands. Don’t say Jesus is for this party or against that party. Don’t say this is the Christian position on this issue. Don’t say faithful Jesus followers must back this agenda, should support this issue. Don’t insist that this or that Christian value ought to have only a one-party solution. Don’t demonize those with whom you disagree.

Political parties don’t get to decide the bounds of what Christians value. Jesus does.

It should chasten all of us in our political pride that the only scene resembling anything like a democratic election in the Bible is when we shout crucify him, casting our vote on Good Friday for Barabbas rather than Jesus Christ. I realize that this probably sounds like a modest prescription. But maybe modesty is the best policy. Given what the Gospel reveals about us and what was required for us, for our redemption, maybe modesty is the best policy.

There is, though, a Gospel promise embedded in Christ’s answer to their question about taxes. “‘Teacher, is it lawful to pay taxes to Caesar or not?’ But knowing their hypocrisy, Jesus said to them, ‘Why are you putting me to the test? Bring me a denarius and let me see it.’ And they all reach into their pockets to produce one.”

But notice, Jesus had to ask for one.

The coin that condemns them under the Law, since it bore another god’s image — Christ isn’t carrying one. His pockets are empty. He alone is righteous. Jesus is our substitute not only on the cross but in his faithfulness. And that righteousness — Christ’s permanent perfect score, the Bible promises — it’s gifted to you, gratis and forever, at your baptism. The currency exchange that matters in Mark’s Gospel isn’t what happens with the moneychangers outside the Temple; it’s what the ancient church fathers and mothers called the great exchange.

In taking the unclean coin from our hands, Christ takes our sin into his own hands. And then two days later he takes our sin in his body to a tree.

The baptism of his death and resurrection is a refining fire that has rendered you purer than silver and more precious than gold no matter what you render to Caesar. Where our pocketbooks prove that we have no king but Caesar, he brought down the mighty from their thrones by being lifted up on his cross — his victory, by grace through your baptism, it’s as though you had won it by your own obedience.

Where we fail to render to God the everything that belongs to God and give a lot more heartburn and bother to the Rome we call America, by grace through your baptism you are credited as blameless as Jesus Christ himself. There is therefore now no undoing it. Don’t do to Jesus what Jesus wouldn’t do to himself. Don’t insist that Jesus fit into your red or blue box. You don’t need to. Because you’ve been gifted Christ’s own righteousness, you have the right to be wrong.

But there’s the rub. So does your neighbor. They have the right to be wrong, too.

COMMENTS

3 responses to “The Right to be Wrong This Election Season”

Leave a Reply

I work for a faith-based organization that produces an annual voter guide on ballot issues (but never candidates, obviously, as a 501c3). While we do take positions and offer perspective, we make it very clear that a person of faith can conscientiously come to any conclusion about any of the measures. I agree when you say we ought not say that a Christian must follow a singular agenda or partisan path.

I do wonder about the impression of Christian quietism that we project, however, if we withdraw Jesus from the public square of politics wholesale. Believe me, people definitely notice when Christians have nothing to say about, for example, hundreds of children being caged at the U.S. border and separated from their parents. I have a hard time conceiving of a Christian who takes the Gospel seriously not responding with some level of moral outrage, and yet so many seem willing to enable it. So, if claiming the “anti-caging children” side is the Christian side is problematic… what kind of witness do we have left? Jesus definitely took positions on issues, on his own terms anyway – e.g. he was definitely anti-money-changers-in-the-Temple. Shouldn’t we have the courage to put our hands and feet and voices, the very body of Christ, to similar use?

☝???? This

There is so much to love about this post. I appreciate the historical storytelling and context, but I mainly appreciate the invitation to being wrong. Many Christians are batting around this idea of political abstinence with the aim of staying pure. A lost cause. By contrast, my loved ones occupy firm stances on either side of current divide. Many of their opinions (left and right) I find outlandish. But they do have justifications for those opinions, and when I open myself to hearing them, I am often surprised and come to a greater understanding, and with that, a greater sense of personal peace. Thanks for a thought-provoking read.