1. Not a particularly easy week to round up, as almost everything out there right now is conjecture of one kind or another, and I’m pretty sure I just wrote something about the pitfalls of prediction addiction. So I’ll stick to the handful of evergreen subjects that’ve come across my screen. First up would be Arthur Brooks’s article in the Atlantic on “one of the greatest paradoxes in American life,” namely, that “while, on average, existence has gotten more comfortable over time, happiness has fallen.” In short, happiness doesn’t increase alongside affluence because we use that affluence to chase the wrong things even harder. Brooks writes:

Consumerocracy, bureaucracy, and technocracy promise us greater satisfaction, but don’t deliver. Consumer purchases promise to make us more attractive and entertained; the government promises protection from life’s vicissitudes; social media promises to keep us connected; but none of these provide the love and purpose that bring deep and enduring satisfaction to life. This is not an indictment of capitalism, government, or technology. They never satisfy — not because they are malevolent, but rather because they cannot.

Holy #Seculosity, Batman! And he goes straight for the jugular in his second takeaway for a happier life (didn’t think we would actually be able to steer clear, did you?):

Don’t put your faith in princes (or politicians). If I complain that government is soulless or that a politician is making me unhappy — which I personally have done many times — I am saying that I think government should have a soul or that politicians can and should bring me happiness. This is naïve at best.

Pre-Order opens Monday!

My own modest prediction (!) for this coming Wednesday is that, whatever happens, we’ll see a profound outpouring of grief. We’ll see this from the side that loses, but, perhaps more subtly and longer term, from the side that wins. Such is the psycho-spiritual investment in Tuesday’s result that we are going to miss the excitement of not knowing (and the fantasy that everything-will-change-and/or-be-answered). We are going to miss the Purpose a campaign provides, especially in terms of the adversaries it allows us to feed off of. Once those adversaries have been defeated or succumbed to, well, we’ll have to deal with ourselves again, won’t we? So clergy friends, be at the ready with something less puncture-able.

Brooks then offers a further disclaimer:

Governments and politicians do affect our lives. But they cannot bring happiness. This point was forcefully driven home to me a couple of years ago by Mogens Lykketoft, the former speaker of the Danish Parliament and a leading social-democratic politician in Denmark. We were filming a documentary about the pursuit of happiness, and in response to a question about Denmark’s famously happy population, he said, “Government cannot bring happiness, but it can eliminate the sources of unhappiness.”

I’m reminded of MLK’s famous saying about the role of the law, that while it cannot make you love someone, it can stop you, hopefully, from lynching them. The law has its place, in other words, and it’s an essential one. But if you think Tuesday’s result is going to change any hearts, including your own, think again. Fortunately, Brooks doesn’t stop the law-giving there, ha. He continues with the following mandate:

Don’t trade love for anything.

I have referenced in this column before a famous study that followed hundreds of men who graduated from Harvard from 1939 to 1944 throughout their lives, into their 90s. The researchers wanted to know who flourished, who didn’t, and the decisions they had made that contributed to that well-being. The lead scholar on the study for many years was the Harvard psychiatrist George Vaillant, who summarized the results in his book Triumphs of Experience. Here is his summary, in its entirety: “Happiness is love. Full stop.”

The current director of the study, the psychiatrist Robert Waldinger, filled in the details. He told me in a recent interview that the subjects who reported having the happiest lives were those with strong family ties, close friendships, and rich romantic lives. The subjects who were most depressed and lonely late in life — not to mention more likely to be suffering from dementia, alcoholism, or other health problems — were the ones who had neglected their close relationships.

What this means is that anything that substitutes for close human relationships in your life is a bad trade. The study I mentioned above about uses of money makes this point. But the point goes much deeper. You will sacrifice happiness if you crowd out relationships with work, drugs, politics, or social media.

The world encourages us to love things and use people. But that’s backwards. Put this on your fridge and try to live by it: Love people; use things.

2. Pretty close to the Greatest Commandment, eh? Yet like all aspects of the law, easier said than done — big time. In fact, as far as I can tell one of the only mortals fulfilling all righteousness these days is the Bossman himself, Bruce Springsteen. David Brooks profiled the rocker in conjunction with the release of his new record Letter to You, and what he found was a paragon of maturity and gratitude, someone who puts a lie to the notion we discussed in last week’s Mockingcast, that somber times call for somber attitudes (or else):

Springsteen is the world champion of aging well — physically, intellectually, spiritually, and emotionally. His new album and film, Letter to You, are performances about growing older and death, topics that would have seemed unlikely for rock when it was born as a rebellion for anyone over 30. Letter to You is rich in lessons for those who want to know what successful aging looks like […] The album generates the feeling you get when you meet a certain sort of older person — one who knows the story of her life, who sees herself whole, and who now approaches the world with an earned emotional security and gratitude […]

“The actual mechanics of songwriting is only understandable up to a certain point,” Springsteen told me, “and it’s frustrating because it’s at that point that it begins to matter. Creativity is an act of magic rising up from your subconscious. It feels wonderful every time it happens, and I’ve learned to live with the anxiety of it not happening over long periods of time.”

Lest we idolize the man — and it’s hard not to — remember that this is the same guy who confessed profound struggles with depression a few years ago. Meaning, the gratitude that Brooks is picking up on co-exists with other, less savory emotions, none of which can be definitively separated from what’s so compelling and/or lovable about his person and work. So to characterize Bruce as “at peace” wouldn’t be accurate:

“The artists who hold our attention,” he told me, “have something eating away at them, and they never quite define it, but it’s always there.”

Even in his 70s, Springsteen still has drive. What drives him no longer feels like ambition, he said, that craving for success, recognition, and making your place in the world. It feels more elemental, like the drive for water, food, or sex. “After all this time, I still feel the burning need to communicate. It’s there when I wake every morning. It walks alongside of me throughout the day … Over the past 50 years, it has never ceased. Is it loneliness, hunger, ego, ambition, desire, a need to be felt and heard, recognized, all of the above? All I know, it is one of the most consistent impulses of my life.”

A lot of the music on this album is about music, the making of it and the listening to it, the power that it has. The songs “House of A Thousand Guitars” and “Power of Prayer” are about those moments when music launches you out of normal life and toward transcendence. For a nonreligious guy, Springsteen is the most religious guy on the planet; his religion is musical deliverance. Like every successful mature person, Springsteen oozes gratitude — especially for relationships.

Sounds like a consensus is forming…

“When you’re young, you believe the world changes faster than it does. It does change, but it’s slow,” Springsteen told me. “You learn to accept the world on its terms without giving up the belief that you can change the world. That’s a successful adulthood — the maturation of your thought process and very soul to the point where you understand the limits of life, without giving up on its possibilities.”

Attaining that perspective is the core of successful maturity. Carrying the losses gently. Learning to live with the inner conflicts, such as alternating confidence and insecurity. Getting out of your own way, savoring life and not trying to conquer it, shedding the self-righteousness that sometimes accompanies youth, and giving other people a break. The owl of Minerva flies only at dusk, as they used to say.

3. A beautiful picture, and I’m pleased to report that the record bears this out. And yet, it’s also one that reminds most of us of how short we fall in comparison. A law that convicts rather than consoles, you might say, which is thankfully where Mbird contributor Charlotte Donlon comes in. She has a book coming out on Nov 10 called The Great Belonging, and in anticipation of the release, Christianity Today ran a stunning (and incredibly timely) portion this week under the heading “I Lost My Dad to COVID-19. The Theology of All Saints’ Day Sustains Me.” Read the whole thing if you possibly can and then order the book, but if you’d like a teaser, here’s one paragraph that will hopefully buoy your spirit as it did mine:

Hope has been pretty hard to come by this year. But on this feast day, God reminds us of our ultimate destination. Having hope in the eventual full realization of the kingdom of God doesn’t take away our sorrow and grief, but it becomes a sort of comrade. It takes our hand and leads us toward what’s true. Yes, we have lost so much, and we will continue to experience loss. But we have also received good things, and we will continue to receive good things. In Christ, we receive God’s presence, comfort, love, grace, and mercy. We receive the ability to empathize and sympathize with others who are where we have been or where we are now. We receive assurance that this place we inhabit isn’t our final stop.

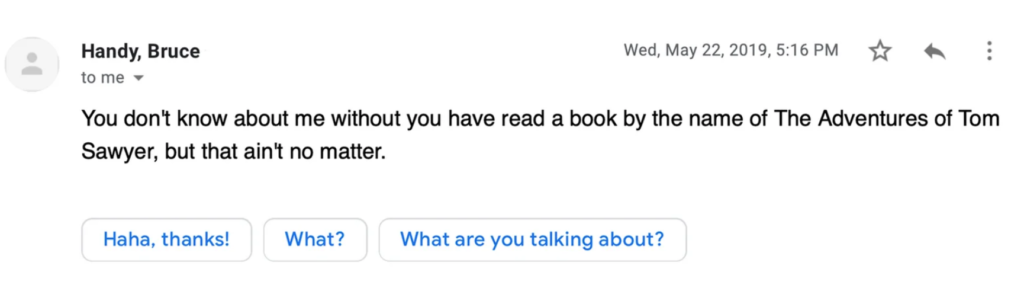

4. Shifting gears (dramatically), in humor, this one from the Hard Times hit uncomfortably close to home, “40-Something-Year-Old Man’s Entire Identity Based on Two-Year Span from His 20s.” And I enjoyed Reductress‘s “How to Stay Humble Even Though You Own the 12-Foot Home Depot Skeleton. But the funniest thing I read this week was definitely “Poems Edgar Allan Poe Wrote While Lost in a Corn Maze.” Oh, and Google Smart Reply, Literary Critic in the New Yorker also yielded a few chuckles, for instance:

On a somewhat related note, my wife and I re-watched the first season of 30 Rock recently and were blown away by how non-stop funny it was, especially in comparison to later seasons. That experience, in tandem with finally reading John Kennedy Toole’s astounding Confederacy of Dunces this year (and watching Letterman’s new Netflix interview with Dave Chappelle), brought home some of the insights in Alexi Duggins’s Guardian column “Why is humour so rarely treated as high art?” Funny is hard:

Writing good comedy is just as valid an artistic achievement as penning more “serious” fare. Even more so, in fact: crafting laughs is the most high-stakes form of creation. It is intrinsically difficult, as “funny” varies from person to person in a way that “sad” or “romantic” just doesn’t. Plus, it is a medium that demands success, because a failed gag is excruciating, like OK-ish results in other artforms never will be. Comic writing is the hardest form of writing, which is a strange thing to consider, given how often the laser-guided wordplay of PG Wodehouse fails to appear on “best novels” lists.

Is it because there is something frivolous about an artform that exists to make people smile? Shouldn’t be. Comedy is a necessity; part of the human experience. Even in the soul-chilling battlefields of the First World War, soldiers told jokes. Gallows victims went to their deaths with quips for final words. So ever-present is the desire to generate laughs that it is tempting to say the truly lightweight cultural works are those that lack funnies. If a film, novel, or TV series features a world where no one makes jokes, it is ludicrous.

5. More than ludicrous, I’d call such a world truly scary. Which is probably a good opening for Mbird contributor Ian Olson’s seasonal article, Tread Underfoot our Ghostly Foe, which appeared on the Living Church website this week:

These forces — the dead, the unseen, the chthonic — complicate our relation to the planet insofar as they hinder or even contest our attempts at control. The affirmation of the New Testament’s witness to nonhuman powers resonates with our sense of there being an unknown, obscured Other intruding itself upon the field of our action, manipulating our anxieties and fears, steering our decisions in directions we could not foresee and would not have chosen ourselves. The unseen realm of nonhuman actants infringes on our efforts to order our lives, sometimes obstructing our efforts to forget, both for good and for ill, sometimes energizing our defacement of ourselves and others. The forces that exert themselves upon us also exert themselves within us. Psychologists locate ghosts within the human mind and they are correct insofar as the spiritual actants we experience as alien and oppressive are simultaneously agents distinct from us as well as uncomfortably close to our inmost selves. For there is a correspondence between these outer phenomena and the inner experience of terror, of guilt, of resentment, which goad us towards action we ourselves do not wholly understand.

No one is immune to such influence, for there is no necessary correlation between fear and belief. Ask many people and they will tell you they do not believe in ghosts but that they are afraid of them. (The same answer is sometimes given when the question pertains to God, interestingly enough.) Fear can be provoked apart from credence in the thing inspiring that fear; after all, one need not believe someone or something in their life is manipulating them in order to be manipulated.

6. Finally, we lost one of the greatest chunks o’ coal ever this week when outlaw country icon Billy Joe Shaver died. The Washington Post published a particularly good obituary, but I recommend revisiting Ethan’s wonderful piece on him from 2012 and then cranking one of the Shaver records (Victory!) or watching this:

Strays

- I had the privilege of appearing on the Thinking Fellows podcast last week to discuss “The Seculosity of COVID.” It was a really fun conversation, as it always is with those guys. Other listening recs include Scott Jones’s recent interview with Alan Jacobs and Malcolm Gladwell talking with Springsteen.

- Why This Professor Is Writing Letters for People Feeling Blue has some gracious overtones.

- I loved Tom Holland’s tribute to the Rev Anna-Claar Thomasson-Rosingh, AKA The Preacher Who Brought [Him] Back to Church.

- In TV: at the behest of several grace antennae-d culture vultures (including our own Howie Espenshied), I’ll be binging Ted Lasso this weekend.

- No matter where you find yourself on the eve of this election, David French’s column on “The Spiritual Blessing of Political Homelessness” is worthwhile.

- Check out this video unboxing the new Mockingbird Devotional!! Pre-order opens on Monday.

- Last but not least, the latest video from Electric Jesus just debuted and it’s another (suitably Van Halen-esque) slice of perfection. If you tune out before the 2:50 mark, you’ll regret it:

COMMENTS

One response to “Another Week Ends: Unhappy Affluence, Aging Springsteen, COVID Grief, High Art Humor, Ghostly Foes, and Billy Joe Shaver”

Leave a Reply

Wow tons of great content here. The commentary on Arthur Brooks’ piece was exactly what I needed to read today.