Grateful for this post by Jason Micheli.

During this hiatus of coronavirus quarantine and online worship, I’ve found myself reflecting on what I’d like to change about the way my tribe of Christendom, the UMC, celebrates the eucharist once we return to recognizable times. The changes I’d like to make have nothing to do with hygiene and germs and everything to do with grammar.

I’d like to excise the adverbs from our communion liturgy.

Any reader already knows the truth of it. Adverbs are the tell of every found-out liar (I whole-heartedly apologize for any offense I might have caused). Adverbs are the trademark of every dime-per-word pulp fiction story (Sam Spade braced the suspect’s shoulders menacingly).

Notice, no children’s book worth the encroachment into bedtime employs the little modifiers. Not because Timmy can’t handle sounding-out “swiftly” but because adverbs aren’t needed for a good and true story.

In case you were sleeping boorishly in high school English class, Stephen King helpfully explains:

Adverbs … are words that modify verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs. They’re the ones that usually end in -ly. Adverbs, like the passive voice, seem to have been created with the timid writer in mind. With adverbs, the writer usually tells us he or she is afraid he/she isn’t expressing himself/herself clearly, that he or she is not getting the point or the picture across.

In On Writing Stephen King asserts that “Fear is at the root of most bad writing.” The fingerprints of the fearful writer are adverbs.

Thank Christ whoever crafted the wedding vows — Thomas Cranmer, I believe. He had the cojones to avoid the adverbial. Consider how the common, seemingly harmless little adverb transforms the marriage covenant from a clear and simple (if terrifying) promise into a Sisyphean endeavor I can never know if I’m upholding aright.

“Will you love her, comfort her, honor and keep her, in sickness and in health; and, forsaking all others, be faithful to her as long as you both shall live?”

vs.

“Will you sincerely love her, whole-heartedly comfort her, genuinely honor and keep her, in sickness and in health; and, resolutely forsaking all others, be faithful to her as long as you both shall live?”

The former is merely an enormous, outrageous, impossible promise requiring a community to hold you accountable to keep it. The latter is psychological torture.

Implied by and requisite to the Gospel is that neither my will nor the rest of me is free. Consequently, I am a stranger to myself. Most especially am I in the dark as to the truth of my motivations. As opposed to Thomas Cranmer, in Stephen King’s estimation, the authors of the United Methodist Church Book of Worship were not likewise bold, for in our eucharistic liturgy what we give in the invitation to Christ’s table we take away with adverbs: “Christ our Lord invites to his table all who love him, who earnestly repent of their sin and seek to live in peace with one another.”

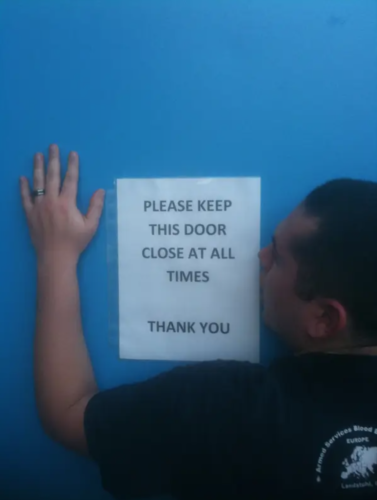

King contends that adverbs signal a timid writer because they betray the writer’s lack of trust in the telling of the story thus far. The timid writer must tell you X slammed the door menacingly because the timid writer doesn’t trust that you can deduce the character’s menacing nature from the fact of his slamming the door. Similarly, the authors of the UMC’s eucharistic liturgy betray a fear about a lack in the Gospel story that they seek to remedy with adverbs. The Gospel’s all about grace, but it can’t be cheap so we got to make sure they’re earnest about their repentance.

King contends that adverbs signal a timid writer because they betray the writer’s lack of trust in the telling of the story thus far. The timid writer must tell you X slammed the door menacingly because the timid writer doesn’t trust that you can deduce the character’s menacing nature from the fact of his slamming the door. Similarly, the authors of the UMC’s eucharistic liturgy betray a fear about a lack in the Gospel story that they seek to remedy with adverbs. The Gospel’s all about grace, but it can’t be cheap so we got to make sure they’re earnest about their repentance.

As the angel Gabriel all but says to Mary and the shepherds, fear is the opposite of the Gospel. So then, the adverb doesn’t just weaken the Gospel — and the sacrament of which it is a sign — it transforms it, from Good News to Bad. From an invitation to the Table of Christ who is the friend of sinners, full stop, to an invitation to the Table of Christ who is the dinner date of sinners who really, truly, sincerely, whole-heartedly, resolutely repent of their sins.

The invitation to the Table, remember, is the Risen Christ’s call to his Table, a Christ who initially received death threats precisely because he ate and drank (too much) with recalcitrant unrepentant sinners and prodigals who had not yet come to themselves. The invitation to the Table, remember, is an invitation to his Table, where we feast on the bread and the wine which are the visible words of his full and final, once-for-all forgiveness of your sin.

Where does a treasonous adverb like earnestly belong in such an invitation or on such a Table? An adverb like earnestly makes your welcome to Christ’s Table conditioned not on the completeness of his cross for you (which happened objectively outside of you) but conditioned upon the sincerity of your interiority.

Of course, the rub is that, apart from the Gospel and its edible form, you’re in absolutely no position to assess your interior state.

If Christ does not welcome me to his Table of visible, edible Gospel forgiveness until I am certain of my subjective earnestness about repentance of sin then, quite simply, the eucharist is not a means of grace but a work of the law, in which case I’m relieved most United Methodist Churches ignore Wesley’s admonition about constant communion.

Let me make it plain. Here’s why I want to stop serving adverbs at the Table:

- The wine and bread are visible, tangible, edible signs of a promise that lies outside of us. Adverbs drive us to look within, the very opposite trajectory of the salvation to which the Table points. The truth of the Table is not determined by your disposition; therefore, the invitation to the Table cannot be premised upon the earnestness of your disposition. The strength of our faith, in other words, lies not in the strength of our faith but in the object of our faith, Jesus Christ and him crucified for un-earnest us.

- The New Testament witness is that we are prisoners to the Power of Sin (Romans 3) such that the good we wish (like coming to the Table in earnestness) is the good we cannot will (Romans 7). In bondage to the Power of Sin, we’re in no position whatsoever to assess our ‘earnestness’ for repentance. As sinners we deceive no one else more so than ourselves. To staple a subjective inventory to the invitation is to insist upon something we cannot do and will only do in sin apart from the grace offered in the visible Gospel of bread and wine. The bitter irony of our adverbial invitation is that the very thing provided by the sacrament (sincerity of repentance given by God) is made a precondition to come to the sacrament.

- The adverb switches the agency. Earnestly. Sincerely. Whole-heartedly. The adverbs shift the focus from what God in Christ has done for us, once-for-all, to what we must do now for God. Adverbs make a hollow mannequin, says Chad Bird, that we nail to the cross in Christ’s place. We imply through the adverbial invitation that it’s the sincerity of our contrition that merits our seat at the Table. Because sinners like us can never know if we’re sincere enough, earnest enough, whole-hearted enough, but the promise of the Gospel, made tangible in wine and bread, is that Christ is the only one who is enough. Adverbs are spiritual quicksand. Christ’s word of unmerited, unconditional forgiveness is a solid rock that creates earnest repentance.

“The adverb is not your friend,” warns Stephen King. Indeed, perhaps nowhere is the adverb more your enemy than when the adverb comes between you and the banquet of heaven, duping you into believing that repentance is your work at all. This is what the street preachers (and most other preachers) get wrong. Repentance is God’s work. As Chad Bird notes, God repents us is the better way to understand it. Repentance is not a work we perform (or a decision we make or a disposition we determine). Repentance is a gift Christ gives. As with the Ninevites, as with the crowds at Jesus’ baptism, repentance is made possible by God’s encounter with us. Whether in his word in the case of Jonah, in Christ in the Gospel, or through word and sacrament, to repent is to be encountered by God.

“The adverb is not your friend,” warns Stephen King. Indeed, perhaps nowhere is the adverb more your enemy than when the adverb comes between you and the banquet of heaven, duping you into believing that repentance is your work at all. This is what the street preachers (and most other preachers) get wrong. Repentance is God’s work. As Chad Bird notes, God repents us is the better way to understand it. Repentance is not a work we perform (or a decision we make or a disposition we determine). Repentance is a gift Christ gives. As with the Ninevites, as with the crowds at Jesus’ baptism, repentance is made possible by God’s encounter with us. Whether in his word in the case of Jonah, in Christ in the Gospel, or through word and sacrament, to repent is to be encountered by God.

The repentance insisted upon in our invitation is the same fare served up by the street preachers, and the reason the street preachers rub us the wrong way is that it’s bad news. It throws all the work back on us and our ability to repent. That’s what leads to judgmentalism; it’s works righteousness. If my repentance is something I can accomplish, then I’m liable to be judgmental about others who couldn’t or chose not to.

The good news is that none of us can repent on our own. We’re all lost sheep in the process of being found. The fact that God repents us, regardless how earnest we feel about the matter is proof — in the eucharist, tangible, edible proof — that God’s complete forgiveness is always prior to our repentance. The latter the product of the former. Jesus Christ eats and drinks with sinners. This is his Table. You’re welcome here. No adverbs necessary.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply