It arrived while we were at the beach. I had almost delayed our trip to be there to receive the package in person. Even from afar I could feel the tectonic plates of my personal archaeology click into place. After decades of dreaming and pining, a copy of New Mutants 87 was mine. We’re talking about the first appearance of Cable, time-traveling X-Man and son of the Fantastic Four, with the iconic Rob Liefeld-Todd McFarlane cover. When I was 13, this issue was a Holy Grail, the comic equivalent of a Ken Griffey rookie card. Can you feel me?

It arrived while we were at the beach. I had almost delayed our trip to be there to receive the package in person. Even from afar I could feel the tectonic plates of my personal archaeology click into place. After decades of dreaming and pining, a copy of New Mutants 87 was mine. We’re talking about the first appearance of Cable, time-traveling X-Man and son of the Fantastic Four, with the iconic Rob Liefeld-Todd McFarlane cover. When I was 13, this issue was a Holy Grail, the comic equivalent of a Ken Griffey rookie card. Can you feel me?

Cause this sort of nostalgia is 100% feeling. No one cares about Cable anymore. Or Rob Liefeld. But we all care about our 13-year-old selves.

When my kids ask me in years to come how I survived the coronavirus quarantine, I’ll have a decision to make. Do I give them the proper answer, which is “by the grace of God and the kindness of your mother”? Or the honest answer of “by means of a near-lethal combination of outdoor exercise and extreme nostalgia”? Because that’s how I’ve muddled through.

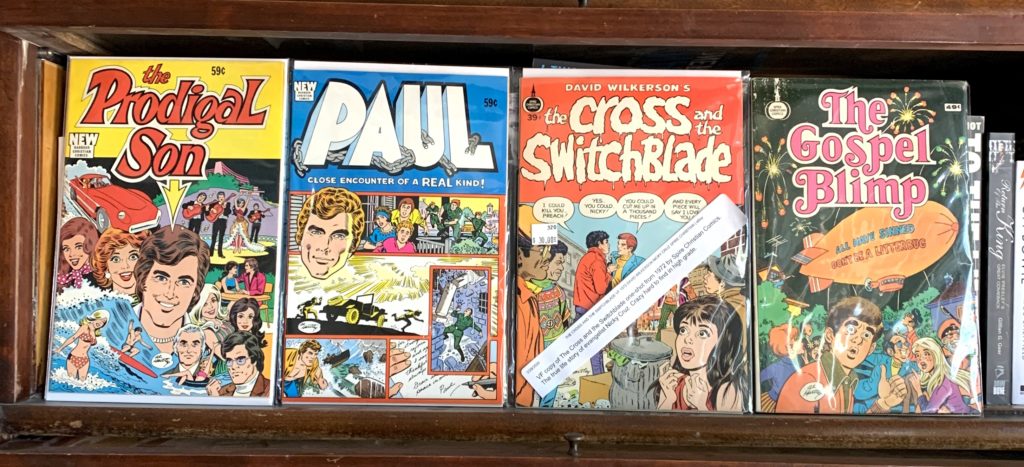

The nostalgia started with baseball cards, moved on to Garbage Pail Kids, then skateboarding, before falling into comic books and grunge records. There’s nothing arbitrary at work here: These were my successive obsessions between ages 8 and 14.

Collections make for great distractions. Spend time with hardcore hobbyists and the psychology is hard to ignore. Esoteric interests funnel a person’s attention away from pain and uncertainty — your eye is literally on the prize — and into a specific area of mastery. Each thrill of acquisition yields to the next target in an addictive haze, albeit one that’s only harmful to your bank account.

Throw a pandemic into the mix, and nostalgia-fueled collecting can become a lifeline. Each eBay purchase gives a person something small to look forward to in lieu of engagements that had been cancelled. We plunder the past to re-establish a future, maybe even to re-establish ourselves.

But that’s not the whole picture. Nostalgia, at least in my case, is more like emotional time travel. When there’s little about the future that seems dependable or encouraging — doomscrolling is more like it — why not direct one’s faith in the opposite direction?

I’m not alone in looking to the past for inspiration, hope, or excitement. Reports of exes getting back in touch with former flames these past few months are rampant. The other day Tom Holland remarked that he’s “more moved by things that have been than things that might be,” and you don’t have to share that core disposition to relate.

At the beginning of the pandemic, some pundits predicted an excess of “emotional movement” during quarantine, that we’d witness a surge of both personal epiphanies and nervous breakdowns, marriages and divorces, estrangements and reunions. Sounds about right. Thought you’d dodged that mid-life crisis? The pandemic is here to catch you up on what you missed.

Thus a man wakes up one day surrounded by responsibilities and rules and decides to hop in the DeLorean and hightail it back to 1985. Not necessarily because he wants to smell the scent of freshly opened wax pax, but because he wants to feel free and hopeful rather than restricted and afraid. Maybe he wants to go full Cable and redeem his present by fixing the past, righting some perceived lack by finally realizing the promise of a certain comic book.

Like other coping mechanisms, nostalgia can, when pressured, consume the sufferer. What starts as a means of diversion and play can become a vehicle of avoidance and denial. You stop fantasizing about attaining the lost baseball card and start to fixate on “the one that got away.” These are dangerous games to play, and yet, when the future seems opaque at best, a sentimental freakout has to be preferable to bottomless prediction addiction.

Or maybe it’s just a different side of the same control-shaped coin. Fantasizing about either the past or the future beats acceptance of the present, right? We may know in our minds that God resides in the here and now — and not some rose- (or doom-)colored projection of what was or will be — but the heart, not the head, operates the flux capacitor.

I was recently asked a question that I hadn’t gotten in a number of years. My friends on The Soul of Christianity quizzed me on when I became a Christian. The cute answer I usually give is the one I borrow from Rod Rosenbladt, namely, that it happened 2000 years ago, on a hill outside Jerusalem. Others might cite their baptism. And those are accurate answers, as far as it goes.

Of course the actual answer has to do with a breakdown in my personal life 20 years ago, a time when both Romans 7 and Romans 8 became experiential (and not just intellectual) realities for the first time. The emotions were so big — and, let’s face it, are so big still — that to revisit them feels almost sadistic. Then again, no less than the apostle Paul seems to constantly revisit his conversion to make sense of his trajectory. That’s where the plutonium is.

I suppose that’s also where the tension for the Christian lies when it comes to nostalgia. Our hope for the future is rooted in the past, both our personal past and the global-historical one. And yet, the risk of turning into a pillar of salt is real. If the hope of the resurrection does not propel us forward, is it really hope at all? I don’t think so.

There’s a classic scene in The Incredibles, where Bob and Helen Parr get into a marital fight over the dinner table. Bob (AKA Mr. Incredible) cannot stop dwelling on his past exploits as a superhero. That part of his life is currently foreclosed, both legally and because of his family responsibilities, and as a result he finds himself distracted and sad and stuck. His malaise compounds an already stressful situation for his loved ones. In what may be that film’s most memorable scene Helen–his wife and former crime-fighting partner–confronts him about it. She needs his help after all:

Helen: Tell me you haven’t been listening to the police scanner again

Bob: Look, I performed a public service. You act like that’s a bad thing.

Helen : It is a bad thing, Bob! Uprooting our family again so that you can relive the glory days is a very bad thing!

Bob: [Defensively] Reliving the glory days is better than pretending they never happened!

Helen: Yes! They happened, but this, our family, is what’s happening now, Bob! And you’re missing this! I can’t believe you don’t want to go to your own son’s graduation!

Bob: It’s not a graduation. He is moving from the fourth grade to the fifth grade.

Helen: It’s a ceremony!

Bob: It’s psychotic!

Escape to the past, especially right now, is not psychotic. It makes all the sense in the world. And yet like so much self-medication, at a certain point what we use to relieve our suffering starts to produce more of it.

What Bob needs is thankfully what Bob receives: grace in the form of Helen’s intervening love. In the moment, yes, the “call-out” inspires defensiveness and retreat. Yet she doesn’t stop there. Soon Bob’s mid-life avoidance has landed him in actual captivity.

Helen snaps into action with a love that does not undermine the past — she dons the uniform after all — but draws on it for the sake of the future. It’s a glimpse of love that transcends sentimentality, attuning itself to present danger by moving with sacrifice rather than recrimination, eventually birthing a response in kind. And a genuinely new beginning.

I know, I know, it’s an animated movie for kids, not holy scripture.

But Lord knows it wouldn’t be the first time a story about (emotional) time-traveling superheroes saved the day. Just read New Mutants 87.

COMMENTS

2 responses to “In Praise of Emotional Time Travel (Sort of)”

Leave a Reply

This is solid!

thanks Jason!