Grateful for this one from Josh Musser Gritter:

Recently I watched the movie adaptation of “The Book Thief”, in which there is striking scene. Set during WWII, a group of German Jews are huddled together in a small bomb shelter outside Munich. As the bombs barrage the city streets, the people of the small town sit in anxious silence. There are no words, but the camera makes you feel the fear. Greater than the fear of bombs is the fear that at any moment the German gestapo could drag them off to the concentration camps.

In the midst of all the chaos and confusion a precocious young school girl named Liesel interrupts the silence and begins to tell one of the stories she read in one of her books. Children gather, parents smile—it’s like children’s church in the bomb shelter sanctuary. Liesel’s story takes them all, if just for a moment, to brighter days and better lands. As the bombs explode around them, peace sweeps through the entire room. That’s what words can do. They are, as Albus Dumbledore would remind us, an inexhaustible form of magic.

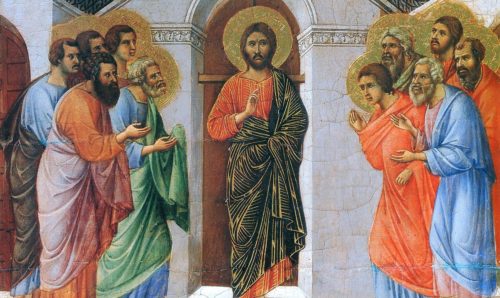

The first Easter was just like that. As John tells it, a rag-tag group of Galileans were huddled together in a small room in Jerusalem. Jesus’ death was a consciousness-altering bomb that obliterated their world and dreams into a million fearful pieces. They had all watched as his breath was taken from him— “Father, into your hands, I give my Spirit.” Note: the word “spirit” here is the common word pneuma, meaning “breathing, breath of life.”

Apparently, on that first Easter morning the disciples had skipped the peeps and champagne. They weren’t celebrating, and neither were they strategizing about who was taking over the reins. They were hunkered down in hiding. At any moment the Roman police who gambled for their Messiah’s clothes could drag them off to an end like his. This Easter I could relate. Though I sat on my porch and shared a very nice glass of very nice resurrection whiskey with my wife and a priest friend in town, I could not shake the feeling that I still had one foot stuck in Good Friday’s junk.

But junk and fear are rich soil for the gospel of grace. Amidst the palpable fear in the disciple’s room, Jesus, the Liesel of John’s story, interrupts the silence. He speaks the word that me and my classmates in Jerusalem learned to say just before sabbath, before the first day of the week (20:19), Shabbat Shalom, peace to you (20:19). Peace is the first word of the new world. The first day always begins with peace.

Jesus then does an odd thing. Translators will tell you “He breathed on” the disciples (20:22). Beyond imagining what a 3-day-in-the-tomb-and-visited-hell breath smells like, I also wonder why translators miss, with one word, what is going on here. Liesel taught us that the magic is in the words, and Yeats said “a line will take us hours, maybe.” Upon a more delighted, imagined reading, one discovers that Jesus doesn’t breathe on the disciples; he breathes into them like how a trumpeter blows into their horn—what a world is contained in a preposition!

In this dusty old room Jesus covers one of the jazziest riffs in Israel’s story. God didn’t breathe on lonely Adam, God breathed into him. “Then the Lord God formed man from the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life” (Genesis 2:7, LXX). Elijah did not breathe onto the dead boy, he breathed into him. The Spirit in Ezekiel’s exilic valley did not breathe on dry bones, but into them. The unfortunate translation probably says less about shoddy Greek work and more about the Western world’s discomfort with the sheer intimacy of this moment. Jesus breathed into them. In Narnia Aslan breathes onto the lifeless statues, but here the image is much closer to CPR. The breath of Jesus does not give COVID, but the life-giving Spirit. This is a kiss of life.

The Spirit of Jesus is Easter’s holy respirator, breathing and kissing resurrection into a fearful world that has lost its breath and running short on hope. If our traditions speak of the Spirit’s life at all—and I must say in my own mainline Presbyterian tradition we do not—we have become accustomed to a rock ‘n roll pneumatology. The Pentecost of Acts will meet us with bursting fire, violent wind, mysterious tongues, a plurality of peoples, and a cacophonous ecstasy. In the American West our language for the Spirit is so saturated in the grand and awesome that those of us for whom life is not always a party rightly dismiss and deny its significance for us. But before God’s Spirit did anything, animated anyone, or exploded anywhere, it was hovering over darkness, dwelling within void.

The biblical writers wanted us to feel the closeness and intimacy of the Spirit’s life in the very sound of its name. This is why both the Greek and Hebrew words for Spirit cannot be uttered without breathing and spitting all over the person next to you. Often in Scripture the Spirit moves in the still, small places. Nowhere is this truer than in the last moments of Jesus—yet another life snuffed out by the Roman vengeance machine. The spirit-breath is the last thing Jesus gives away, “Into your hands, father, I give it.” This very same Spirit fluttered over George Floyd as his breath was taken from him. No matter how cruel and inhumane the death, it is impossible that any human die alone, for as in our beginning infant’s breath, the Spirit is there to the bitter end.

John’s underwhelming Pentecost moment happens not with a bang, but with the breath of a whisper. It happens in the muted tones of a small room filled with scared friends, it happens with a breath, a kiss, when God whispers new creation into lifeless lungs. Especially now we need this account of the Spirit, the one who despite our social distance and breathlessness is now kissing and breathing life in living rooms, hospital corridors, on neighborhood porches, and in city streets.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply