Thankful for this one from Grant Wishard.

Im Chaem, a delicate woman in her mid-70s, lives peacefully in the tiny village of Anlong Veng in northwest Cambodia. She raises cucumbers, tends to several cows, enjoys Thai soap operas, and is content to pass the time away with her loving children and grandchildren.

Im Chaem is also the most harshly described character you are ever likely to meet in the pages of a responsible news publication. In a recent article from the South China Morning Post she is described as a “wiry, shrew-like grandmother” who “scuttles” and points at things with her “claw-like” hands. Her remaining teeth are darkly stained and she “hisses” her answers to questions from the reporter. It seems like several too many verbal uppercuts for a featherweight elder, unless that elder was once a senior official in Pol Pot’s ruthlessly genocidal regime.

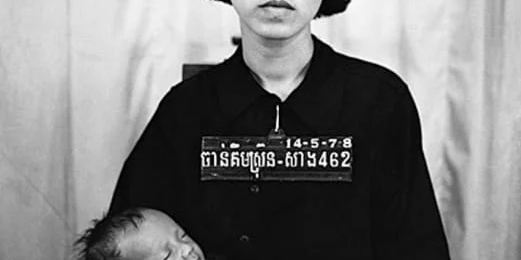

In the 1970s, Im Chaem was assigned to the northwest part of the country to find and destroy traitors, organize prisons, and build massive infrastructure projects with slave labor, all in the delusional pursuit of a Marxist utopia. “Her name was known to everyone,” said Youk Chhang, a survivor who worked on one of Im Chaem’s projects as a 14-year-old. “People would be made to work all day and all night with no water. People would be killed right in front of you. She was the image of the regime’s brutality.” Enthusiastic and highly efficient, she supervised the deaths of an estimated 560,000 people.

Though she objects to the interpretation of events, Im Chaem has never denied her role in the regime. A Cambodian court backed by the UN charged her with almost every crime there is — murder, extermination, enslavement, imprisonment, torture, persecution, enforced disappearance, rape, forced marriage, and confinement in inhumane conditions — but she will never be punished in any way for her cruelty. The charges were dismissed. But only because Cambodia has a complex relationship with its own past. Not because anyone imagines Grandma Im Chaem is a sweetie.

Im Chaem is a nasty, wicked person. Like all genocidal maniacs in their 70s, she must have a lot to think about. When the New York Times tracked Im Chaem down three years ago, she was found listening to Buddhist talk radio. She told reporters that she was a donor to her local pagoda and spent much of her time reading the Buddhist scriptures and waiting to die. “I just learn the Buddha’s advice and keep the holiness within myself for my own sake,” Im Chaem waxed philosophically. “Having the holiness in myself makes me good, not killing anyone or criticizing anyone. That is the holiness in myself: to make myself good.” No doubt, the half million sent to their grave by Im Chaem wished she had listened to the Buddha back then. Or had been smited by him or a more aggressive god. Or received an icepick to the skull when it really mattered.

The recent South China Morning Post article, however, confirms a startling bit of inter-faith gossip. Im Chaem has converted to Christianity. She was baptized by Christopher LaPel, who slaved away on Im Chaem’s dam before he was able to flee to the United States where he became a pastor. Im Chaem is only the most recent of several high-ranking regime officials to be converted by LaPel, who lost his parents, brother, and sister to the genocide. Im Chaem has opened a church in her own compound and has optimistically filled it with more plastic chairs than would ever be needed in a region that is almost entirely Buddhist.

The recent South China Morning Post article, however, confirms a startling bit of inter-faith gossip. Im Chaem has converted to Christianity. She was baptized by Christopher LaPel, who slaved away on Im Chaem’s dam before he was able to flee to the United States where he became a pastor. Im Chaem is only the most recent of several high-ranking regime officials to be converted by LaPel, who lost his parents, brother, and sister to the genocide. Im Chaem has opened a church in her own compound and has optimistically filled it with more plastic chairs than would ever be needed in a region that is almost entirely Buddhist.

Im Chaem’s reasons for converting are extremely complicated and nuanced: “I became a Christian to save myself.” Just kidding. Free of pretense, tedious apologetics, and all denominational snobbery, Im Chaem’s testimony is refreshingly blunt and almost that of a consumer. “Jesus can save you if you are a sinner, and that is why I converted to Christianity,” she explained. “Only Jesus can redeem you. Only Jesus can wash your sins away.” She tried Communist atheism and she tried Buddhism. She must know that people dismiss her conversion as self-serving and guffaw at the idea of her in the good place, but she is on her knees nonetheless. She is safe from the courts, loved by her family, and accepted by her country — she has nothing to gain on earth from converting — but she is thinking about eternity and admits she needs absolution. It’s that simple.

Those raised in the Church might be prone to forget what is most offensive about Christianity. It is not the rules. It is the forgiveness. Im Chaem, like all of us, is the penitent thief on the cross but the sheer magnitude of her evil accomplishments and the fact that she will never be punished for her crimes makes that difficult to recognize. The world hates that Im Chaem is physically and spiritually free, but it hates the Christ who offers to forgive her even more. It hates the idea that in the final reckoning, average people who tried to be good their entire life will need forgiveness just like Im Chaem and it hates the idea that forgiveness has been offered to Im Chaem in the first place. And this is understandable because these are terribly offensive claims. Unless, of course, you believe Jesus is who He claims to be.

Image credits: the Archive Team (edited)

COMMENTS

4 responses to “Offensive: On War Crimes and Forgiveness”

Leave a Reply

Powerful.

I love the simplicity in those last two paragraphs. Thanks, Grant. So good

I’ve read this article several too many times. Thought-provoking.

Thanks Grant!!