Look! Up in the sky! It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s a man with superpowers, a closet full of skeletons, a chest constricted by anxieties, and a diagnosis of PTSD, all from saving the world!

Whether we’re stuck on a hurtling train with the brakes cut, in a fiery building we can’t escape, or have a bomb strapped to our chest from a supervillain, I think we can all agree, the superhero we want saving us isn’t the one who’s as dysfunctional as we are.

No, we want someone else. Someone invincible, impermeable to the pain, sin, and Law we are burdened with on the daily. We like our superheroes unrealistic, with a strength unmatchable. We want the alien from Krypton who can shoot heat vision from his eyes and bears an untattered S on his chest, whose only weakness is an element conveniently rare and difficult to find. (Unless you’re Batman, in which case you most likely have some stored on your utility belt, just in case.) We want the high school kid who is somehow hormone-free and unaffected by mood swings to web-sling us to safety. We want the rich man to use his gadgets to keep our city safe without our hearing about his trauma left over from Crime Alley. We want something greater than us to save us.

This perhaps explains the recent backlash within the comic book community against famed writer Tom King. He is currently the writer on the main Batman series, soon to be replaced by James Tynion IV. King’s Batman is one who is relatable. He doubts himself, he is weak at pivotal points, and he is conflicted by the love he has for Catwoman. In the story arc “City of Bane,” which the whole series has built up to, Batman has lost total control of his city and is forced out. He leaves it unattended and run by criminals like Bane, Two Face, Joker, and his father Thomas Wayne who is actually Batman from an alternate universe (long story). He hides away with Catwoman, who helps him gain his strength back. This links them together so much so that King is leaving the series to begin a Batman/Catwoman standalone series.

But making Batman vulnerable isn’t the only controversial work King has done. In The Vision, he paints a picture of an android who just wants to be normal and can’t fit in. Mister Miracle is focused on an escape artist who seems to be able to get out of everything except the trauma of being raised by a supervillain god and of his own suicidal tendencies.

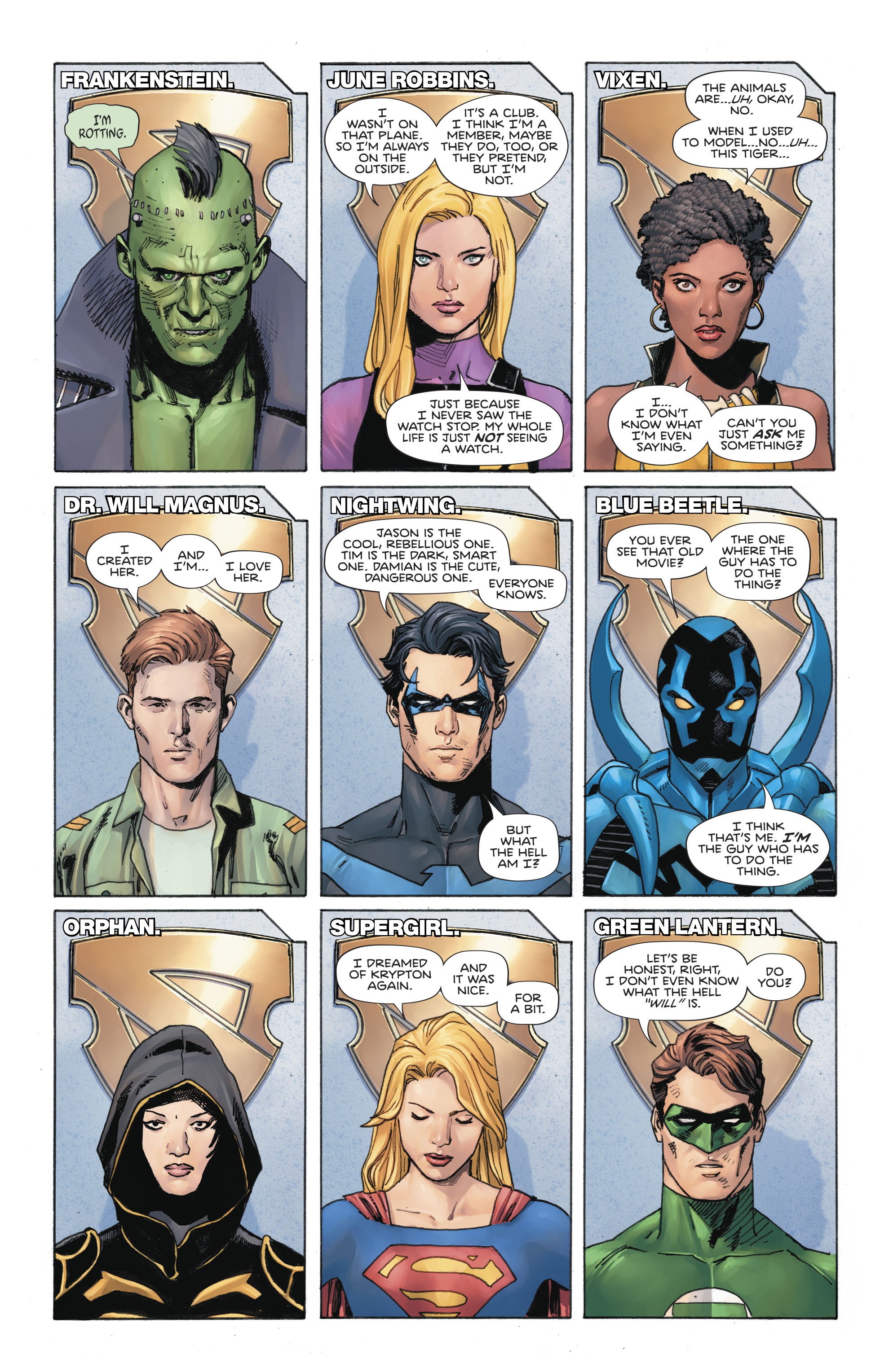

Then there is King’s most recent project Heroes in Crisis, which includes a host of superheroes distressed and weighed down by the heavy law of superheroic expectations. Batman, keenly aware of these problems, creates a safe haven for the troubled heroes, calling it the Sanctuary. It is a place where one can have anonymity and confess to an A.I. program. This is where they will find freedom, where they will come to grips with where they’ve fallen short as heroes. Here, Superman is free to wonder the same things we do: What if so-and-so found out about this? What if who I really am came out? What if everyone knew I wasn’t as put together as they perceive me to be? Or there’s Batman who is overburdened with guilt: I train…partners to work with me. They become…my…family. I’ve watched…so many of them…die.

The comic is full of paneled pages where the heroes stand like a mugshot and confess. Some admit their tendency to fall back into addiction. Some reveal the guilt they’ve felt after people died because of the mantle they’ve chosen to assume. Others own up to how they haven’t saved as many lives as they wish they would’ve.

The comic is full of paneled pages where the heroes stand like a mugshot and confess. Some admit their tendency to fall back into addiction. Some reveal the guilt they’ve felt after people died because of the mantle they’ve chosen to assume. Others own up to how they haven’t saved as many lives as they wish they would’ve.

This is where King shows us the power of the Law: It finds us all and crushes every last one of us. Even those we look up to and cling to, in hopes of moral improvement—even they turn out to be souls searching for a place to be known and accepted just like the rest of us.

King’s pen hits the paper like a gavel, but on the flip side he’s also scribed mercy and absolution in the freedom to confess safely at the Sanctuary. Disturbances happen there, including a a deadly PTSD outburst from the Flash, yet this safe retreat still offers hope. Heroes in crisis all over the DC Universe come and confess, finding open arms to greet them at their arrival.

Of course, while I love me some confident, night-ruling Batman and web-slinging, sarcastic Spider-Man, I do enjoy versions of heroes that are relatable. They’re not far off from the heroes of the faith we have in Scripture. Oftentimes religious communities, not unlike comic communities, want the heroes of biblical faith to be moralistic mentors, exemplifying a state we too can achieve with good works and faithfulness. We don’t want drunk Noah, naked in his tent. We don’t want Abraham abandoning his wife and laughing at God’s plans. We don’t want King David’s adultery and plots for murder. We don’t want them broken, weak, or sinful, since if they can’t meet the demands of the Law, then can we? Can anyone?

Thankfully, we too have a sanctuary like the heroes in crisis. We too have a sanctuary where we can come and confess. We too have a place where we can be accepted as we are, baggage and all. However, our sanctuary isn’t found in a location but rather in a person and a good word. One that whispers to us, even in our worst crisis, “all is well.”

COMMENTS

2 responses to “Tom King’s Pen: a Gavel and a Sanctuary”

Leave a Reply

The problem with King’s Batman is that he’s actually NOT relatable. He’s not relatable because the way he’s being portrayed flies in the face of 80 years of well-crafted characterization. Basically, for anyone with a history of reading Batman, you pick up a Tom King book and you say to yourself, “That’s not Batman.” Because it’s not. It’s obviously just Tom King projecting himself onto the character. Which, considering King was entrusted with legacy of this character, is just downright selfish. Batman’s archetype traces back through Zorro and Robin Hood to the avenging knights of the chivalrous period. We know that archetype intuitively. King’s deconstruction doesn’t feel profound but, rather, like a betrayal. Batman’s “vulnerability” is not that he’s sad or lovesick. His vulnerability is that he’s a man without superpowers operating in a superpowered universe. THAT is where he’s always been relatable to the readers. That he punches so far above his weight is what makes him a hero. It’s what’s inspiring about him. And that’s what pretty much what every Batman writer up to King grasped. But King doesn’t. His run can’t end soon enough for me.

only a couple more issues! almost there!