What brought you here was your insatiable appetite for a juicy mystery.

– Emile Mondavarious

Imagine a cool, moonlit night. Skeletal trees line a narrow gravel road, and headlights are glowing in the distance. A vehicle is coming: an old, sputtering pick-up steered by some middle-aged mustachioed man. A groovy, slightly haunting tune plays as, out of the truck bed, climbs a knight in armor. The knight peers through the truck’s back window, then, mysteriously, the scene fades. These are the first moments of the first episode of Scooby-Doo, Where Are You?, which premiered one otherwise average Saturday morning in September, some fifty years ago.

A wolf howls, and we find Scooby-Doo and Shaggy, too, unassuming yet soon-to-be iconic characters strolling along that same gravel road. Shaggy says, “What a nervous night to be walking home from the movies, Scooby-Doo!” It’s an appropriate opener, because when it comes to this show, there are plenty of things to be nervous about, and the title is one of them. Aside from its convenient rhyme, Scooby-Doo, Where Are You? also betrays the titular character as missing-in-action. Come face to face with a ghostly clown, or a witch stirring brew, and you really could use the companionship of a four-legged beast, but he is probably somewhere else eating a large sandwich or sniffing out a red herring.

A wolf howls, and we find Scooby-Doo and Shaggy, too, unassuming yet soon-to-be iconic characters strolling along that same gravel road. Shaggy says, “What a nervous night to be walking home from the movies, Scooby-Doo!” It’s an appropriate opener, because when it comes to this show, there are plenty of things to be nervous about, and the title is one of them. Aside from its convenient rhyme, Scooby-Doo, Where Are You? also betrays the titular character as missing-in-action. Come face to face with a ghostly clown, or a witch stirring brew, and you really could use the companionship of a four-legged beast, but he is probably somewhere else eating a large sandwich or sniffing out a red herring.

Despite the ever-present question mark, viewers can be sure of a few things. First, the mystery will be solved; what’s more, it will most likely be that same seemingly incompetent Scooby-Doo who will capture the villain, just probably by accident. Often, Scooby appears to be sabotaging the mission. In the pilot, his first role is problem: he and Shaggy are walking home late “all because [Scooby] had to stay and see Star, Dog Ranger of the North Woods—twice.” Later, Scooby knocks off Velma’s glasses (“I can’t see without my glasses!”), and while searching for them, she trips the unscrupulous knight who then falls into medieval, conveniently placed stocks. Somehow the knight escapes, yet luckily Scooby is available to accidentally fly a plane into him, revealing — “It’s the curator! Mr. Wickles!” — the only suspect in the episode.

As viewers, we can relate. The good we try to do so often makes things worse à la unsolicited advice, sending money to a corrupt justice initiative, or knocking off Velma’s glasses while in hot pursuit of a scoundrel. The inverse also occurs: our best deeds may be occasionally caused by accident; sometimes we will not even realize we did anything. Maybe you made a terrible mistake that worked out for the best or said some nice thing you don’t remember saying. So goes the perverse cycle of daily experience, which we’re rarely capable of micromanaging the way we wish we could. Every once in a while, it’s true, Scooby-Doo finds a shoe, sniffs his way directly to a missing person. But the outrageous accidents by which the mysteries are ultimately solved are what we mostly remember and love about this humanoid dog. The truth is revealed but never in the way we anticipate.

Trivia: Scooby is what breed of dog?[1]

In original run, the same images were recycled episode to episode, and sometimes even within the same one. Due in large part to this texture of cheapishness, few critics would remark that Scooby-Doo was ever any masterpiece but I completely disagree. I have no idea what Saturday morning cartoon standards were in 1969 but at least the mood is gripping, even bewitching. The landscapes are beautiful, strange, spectral, and true; in my opinion the overuse of the word “spooky” is something to be celebrated. Every “zoinks” and “jeepers” is a bolt holding in place the show’s eerie frame. Plus, traces of a zeitgeist we can now only dream about: a funky van, silk scarves tied around elegant necks, root-beer floats slurped through striped straws after an evening’s work is done.

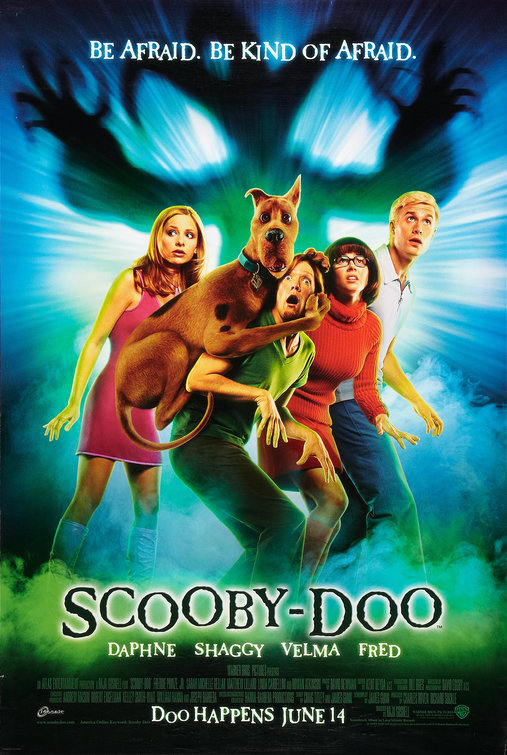

Fifty years in, we could honor any number of Mystery Inc. reincarnations, since there as many as the stars in the sky. There have been at least fifteen different animated series plus live-action adaptations. There were The New Scooby-Doo Movies, hourlong episodes featuring guest celebrities both fictional and real; then there was the over-rated Scooby-Doo and Scrappy-Doo and the underrated A Pup Named Scooby-Doo. But the iteration I now find most noteworthy is also very possibly the worst: the live-action Scooby-Doo (2002), which is just old enough to be nostalgic. Aside from the superbly cast Mr. Bean as the mysterious Emile Mondavarious, and some genuinely funny/exciting moments (particularly the hotel chase, midway through), this movie was a letdown from start to finish, and not merely for production value.[2]

The gang’s ghastly social dynamics merit an entire critique, but for now all that needs to be said is that the group is a mess of self-absorption. Daphne insists that she can solve a mystery without any help![3] Velma meanwhile sets out to prove she is more valuable than Fred, who has become a textbook narcissist. And when, inevitably, they all go their separate ways, Shaggy finds solace in his loyal dog ‘Scoob’. Their relationship is the film’s highlight; it proves enduring, true to the series’ heart. From the cartoons, we knew that when it came to social standards, Shaggy never had much going for him. He ate dog food. He could not grow a beard, instead displaying a few scraggly hairs from a shapeless chin. But as the 2002 project shows, out of this dejection shines the unfaltering love of dog.

The gang’s ghastly social dynamics merit an entire critique, but for now all that needs to be said is that the group is a mess of self-absorption. Daphne insists that she can solve a mystery without any help![3] Velma meanwhile sets out to prove she is more valuable than Fred, who has become a textbook narcissist. And when, inevitably, they all go their separate ways, Shaggy finds solace in his loyal dog ‘Scoob’. Their relationship is the film’s highlight; it proves enduring, true to the series’ heart. From the cartoons, we knew that when it came to social standards, Shaggy never had much going for him. He ate dog food. He could not grow a beard, instead displaying a few scraggly hairs from a shapeless chin. But as the 2002 project shows, out of this dejection shines the unfaltering love of dog.

Trivia #2: What’s Shaggy’s real first name?[4]

The other redemptive thing about Scooby-Doo (2002) was not, on its surface, redemptive. Mainly, the main dog was not even a dog, not really. He is a fuzzy, anthropomorphic, CGI part-animal thing. And because of these abysmal special effects, Scooby is, by his very make-up, one-of-a-kind. Note, there are other dogs in the movie, real dogs; Scooby is not of their kind.[5] He sports, as always, a collar evocative of the Superman logo. Typically, Scooby walks on four legs, but when it suits him, he walks on two, such as when he disguises himself as an elderly woman on an airplane, or when he boxes with the villain in “Scooby-Doo and a Mummy Too,” or when he dons a trench coat, mustache, and bowler hat in “Hassle in the Castle.”

So the main reason I mention Scooby-Doo (2002) is that it captures who our hero is and has been all along. You don’t need to be a crime-solver to sniff out where I’m going with this. But let me make it plain. In the first live-action adaptation, Scooby is lured out to Spooky Island, where he is identified as a distinctly “pure soul.” In this regard, Fred, Velma, Daphne, and Shaggy all fail. An ancient voodoo ritual becomes the bizarre crux around which the film’s mystery revolves, and it is only Scooby who is pure enough to be offered up. Scooby, we learn, is the perfect sacrifice…!

*

As for ghosts, I’ll just say this: I don’t believe in them personally. I mean, maybe I could be swayed. I don’t know. But I do doubt the way the ghosts are depicted in films like The Conjuring, or Ghostbusters, both of which I love but for different reasons. Anyway, Scooby says a different thing. What Scooby says is, the monster is not real. In fact, it is the only suspect there is, in a costume; obviously it is Pietro the puppet master, merely disguised as a phantom.

Remember in “Hassle in the Castle” when the gang witnesses a ghostly apparition passing through a solid wall? Famously Velma declares, “There’s a very logical explanation for all of this… The place is haunted!” But of course, it is not. It is only a projector and a skillful magician using mirrors. The object of our fear is rarely so frightening as not knowing what it is, and what it is is usually the most obvious thing in a mask. Unknowing magnifies the enemy until it transcends comprehension. What becomes a solution is a pulling-off of the mask, a confrontation with the truth, then everyone breathes easier.

Remember in “Hassle in the Castle” when the gang witnesses a ghostly apparition passing through a solid wall? Famously Velma declares, “There’s a very logical explanation for all of this… The place is haunted!” But of course, it is not. It is only a projector and a skillful magician using mirrors. The object of our fear is rarely so frightening as not knowing what it is, and what it is is usually the most obvious thing in a mask. Unknowing magnifies the enemy until it transcends comprehension. What becomes a solution is a pulling-off of the mask, a confrontation with the truth, then everyone breathes easier.

But not always. There was a time on a particular Moonscar Island when pulling off the mask did not work (1998); the monsters were real. Lesser known but no less chilling are The 13 Ghosts of Scooby-Doo, a miniseries that ran in 1985 and featured Vincent Price amidst other supernatural entities. Prior even to this, as a perceptive viewer pointed out on reddit, traces of the supernatural could be seen throughout the show, even its earliest episodes, whether an inexplicably floating ham sandwich or a bone hovering over the earth. All along, this thread has been present, or at least not-for-sure. There has always been the smallest crack, the tiniest doubt in Velma’s coolly rational mind that maybe it’s not just a trick of the light.

With each new iteration came the increasingly fevered tagline: “This time…the monsters are real!” Yet Scooby’s same old crime-solving tactics — slipping, crashing into things — remained infallible even when the laws of the natural world were. Regardless of where we found ourselves on the supernatural spectrum, resolution always came incognito, in the form of an accident or even, on the face of it, something terrible. Think of the central fixture of Christianity, that instrument of death that, in faith, also represents life. It’s a spooky, brutal thing, and many secularists understandably identify its inherent absurdity. But I think of Scooby. We can’t say whether he ever knew exactly what he was accomplishing while blindly riding a jackhammer into Redbeard and a pile of tires, or while luring a werewolf over a waterfall. Probably no; probably he was flailing helplessly. But it always worked. In any case, the gang found closure through the clumsiness of something like the cross or an airplane piloted by a dog speaking English but with Rs at the beginning of each word.

In early phases, the show’s creators wanted to call it Who’s S-S-Scared?, a proposal that was speedily rejected by the network. The concept and artwork were too frightening; kids wouldn’t be able to handle it. Add to that, Scooby was not yet the center of the show, but a mere player in a series about a crime-solving rock-band. (Originally Scooby was called Too Much, which, we can agree, is a pretty good name for a dog.) In revisions, though, as history shows, Scooby became Scooby, named by the show’s executive after he had listened to Frank Sinatra’s “Strangers in the Night.” The dog became the heart of the program, and things got better. Lighter.

Return for a moment to the opening scene of “A Clue for Scooby-Doo.” On a gloomy, cold-looking beach, the gang is doing some risky things: surfing in the dark, dancing robotically at night. Tucked into the sand is an open umbrella, but it’s hard to know why. And still: the vibes are as warm as they are creepy, as fun as they are frightening; with Scooby — absurd, cowardly, bighearted — things feel right. Both safe and dangerous, but in an appropriate dosage.

Like Stephen King’s Castle Rock, or Stoker’s Transylvania, the haunted landscapes of Scooby-Doo represent more than meets the eye. They reflect everyday life and the human mind: a structure that is not all right. Shadows prevent you from knowing all of what’s there. Yet with Scooby as their guide, children across generations have been led safely through the dark. As Daphne says, “Nothing’s impossible when you’ve got Scooby-Doo around.” Daphne also says, Shaggy is the “swingingest gymnast in school!” but that’s beside my point. Anything is possible with Scooby-Doo, is my point. With Scooby, we follow the Mystery Machine wherever it takes us, into coves, caves, bayous, castles, trusting that the mystery will be solved, because we do not go in alone. And because we always have arms to jump into when things get spooky.

[1] Great Dane. Iwao Takamoto intentionally drew Scooby as the precise opposite of a prize-winner, with “overly bowed legs, a double-chin, and a sloped back, among other abnormalities.”

[2] There is also a movie slated for 2020 (animated I believe), with Gina Rodriguez as Velma, so that couldn’t be more exciting.

[3] One might imagine this über-proud Daphne was intended as a corrective, yet, one also wonders, a corrective to what? True, in the cartoon, Daphne is “accident prone.” But consider that, in episode 2, after sliding through her first trapdoor, Daphne says not “Help me! Help me!” but instead, “I wonder how I get out of this creepy inner sanctum. Well, my intuition tells me—” and a ghostly hand emerges at her back, reaches toward her “—that way!” and off she walks to safety. Unfazed! Consider, too, that cartoon Daphne is the most acidic of the group, occasionally making smart if belittling comments off-the-cuff. Did she really need more self-esteem?

[4] Norville.

[5] Admittedly, Scrappy-Doo, like Scooby, is a terribly CGI’ed dog. But in the world of the film, even Scrappy takes on the aforementioned otherworldly quality, embodying, towards its end, Scooby’s devilish nemesis. So I think the point stands. These are no mere doggos.

COMMENTS

3 responses to “Ruh Ro … Fifty Years of Faith in Accidents”

Leave a Reply

This is astounding!!! CJ, you are gift to us all (just like Scooby). Also: Norville!

Epically good!

Love Scooby-Doo and love this!