This poetry review was written by Joey Jekel.

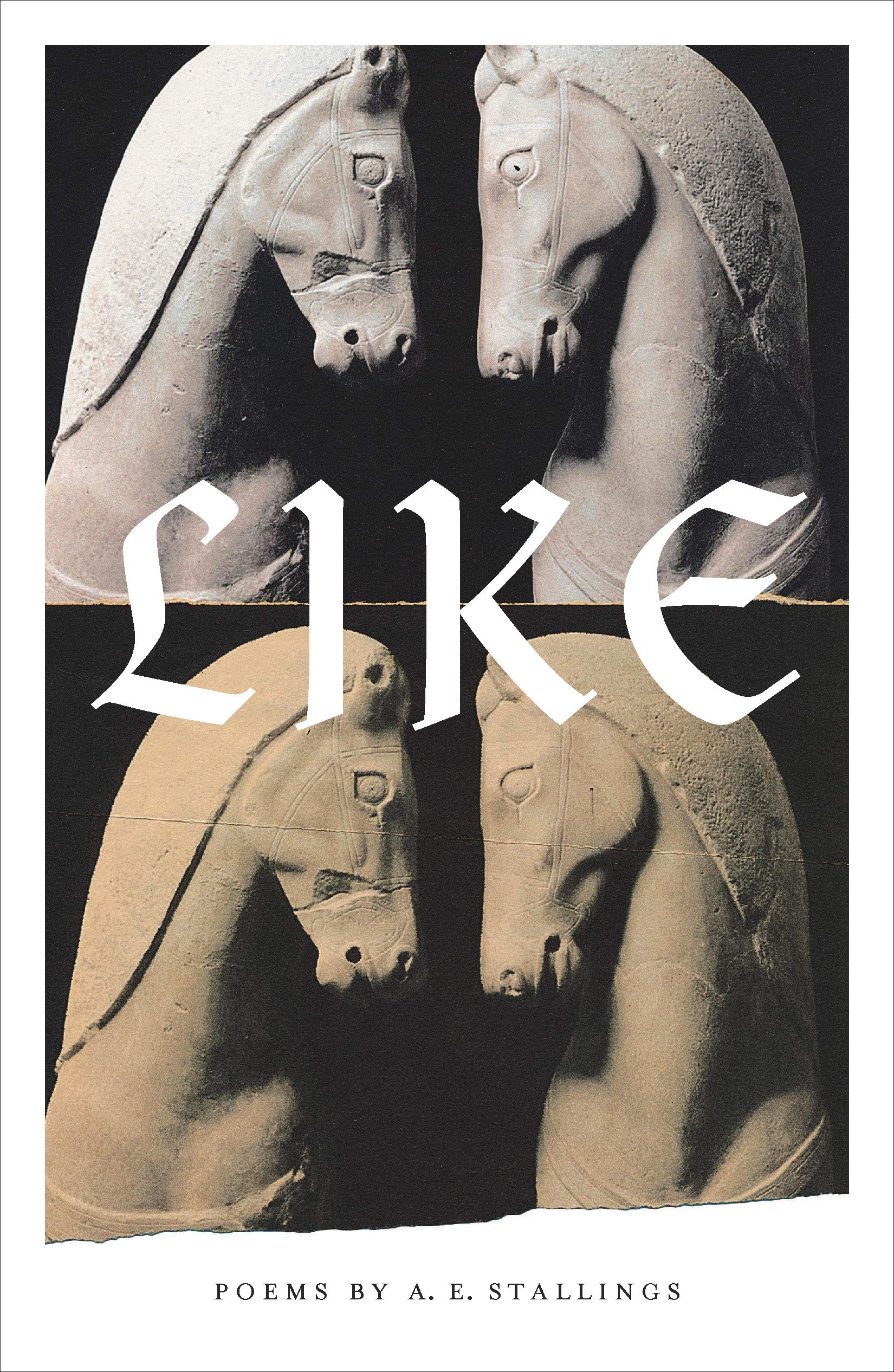

What do translations of Homer, the Eurasian refugee crisis, blacksmithing, and Alice in Wonderland all have in common? They are all in the strange and pleasing ken of A. E. Stallings. A previous resident of Athens, Georgia and current resident of Athens, Greece, this contemporary poet and translator sets out on her most ambitious collection yet, Like, a book of 57 poems and translations.

This collection of poems hinges on its title poem, “Like, the Sestina,” which Stallings positions in the middle of her alphabetized collection. Stallings writes this poem using the same word for the end of every line: “like” appears a total of 50 times in this short poem. She illustrates how mere affection has displaced love, as we most evidently see in the height of social media. Platforms like Instagram encourage a limited engagement with other people, making us believe that a little, red heart is the same as, or better than, invested love. “But it’s unlikely Like does diddly,” Stallings amusingly puts it. The word “like” in American culture seems so meaningless, having come to be used more for filling space than showing connection between two objects. However mocking this poem can seem, it does not end in woe over the world, but a call to love:

This collection of poems hinges on its title poem, “Like, the Sestina,” which Stallings positions in the middle of her alphabetized collection. Stallings writes this poem using the same word for the end of every line: “like” appears a total of 50 times in this short poem. She illustrates how mere affection has displaced love, as we most evidently see in the height of social media. Platforms like Instagram encourage a limited engagement with other people, making us believe that a little, red heart is the same as, or better than, invested love. “But it’s unlikely Like does diddly,” Stallings amusingly puts it. The word “like” in American culture seems so meaningless, having come to be used more for filling space than showing connection between two objects. However mocking this poem can seem, it does not end in woe over the world, but a call to love:

But as you like, my friend. Yes, we’re alike

How we pronounce, say, “lichen,” and dislike

Cancer and war. So like this page. Click Like.”

This poem seems set apart as the standard by which to view the rest of the book, not just as its title and central poem but as it shows Stallings’ hallmarks as a poet: her sense for tragicomedy, her linguistic playfulness, and her ultimate concern with love.

Stallings’ tragicomic vision comes to the surface in a poem called “Alice, Bewildered,” which centers on the amnesic confusion of Alice from Alice in Wonderland. This poem recounts Alice’s loss of self in this new, strange world to which she awakens. Alice loses the “syllables that meant herself” and becomes “un-twinned from the likeness in the glass.” The poem mourns Alice’s temporary amnesia but does not content itself to end with mere sorrow. One word in the final line forcefully carries the minute sense of joy in this poem:

Yet in the dark ellipsis she can tell,

She’s certain, that her name begins with “L”—

Liza, Lacie? Alias, alas,

A lass alike alone and at a loss.”

The pivotal word of comedy in these lines is the word “alike,” which primarily shows the reader that Alice is both alone and at a loss. The word “alike” tells the reader that Alice is alone and, in addition, she is at a loss. Yet, I think this word also communicates that others experience the loss of self that Alice has come to know. Therefore, the poem ends with a paradoxical joy—she is both alone and not alone, both sad and joyful at knowing that she is not alone in her loneliness and loss. Alice’s connection to the pain of other people offsets her tragic loss of self.

Stallings often wears an incredibly playful and, some might say, esoteric persona. As a woman trained in classical Greek and Latin, she often finds herself writing poems with linguistic tricks and educated word games that flex her classical training, which I appreciate as a student of Latin. A significant example of this appears in the poem, “Sea Urchin,” in which the poet uses typographical marks (asterisks and ellipses) in order to describe sea urchins and the wounds they inflict. First, the sea urchins “whisker their risks / in the fine print of footnotes’ / irksome asterisks.” The sea urchins in this poem quite literally inhabit the footnotes, existing below the feet of unfortunate individuals vulnerable to their punctures. In addition, the urchins themselves resemble asterisks (*). Second, “Their extraneous / complaints are lodged with dark dots, / subcutaneous / ellipses…” The wounds the sea urchins inflict on these feet, “soft underbellies,” resemble ellipses (…). Stallings uses typographical marks in order to detail a picture of sea urchins and the injuries they inscribe on human feet. This use of typography clues us into Stallings’ intellectual playfulness in the poems of Like.

Stallings often wears an incredibly playful and, some might say, esoteric persona. As a woman trained in classical Greek and Latin, she often finds herself writing poems with linguistic tricks and educated word games that flex her classical training, which I appreciate as a student of Latin. A significant example of this appears in the poem, “Sea Urchin,” in which the poet uses typographical marks (asterisks and ellipses) in order to describe sea urchins and the wounds they inflict. First, the sea urchins “whisker their risks / in the fine print of footnotes’ / irksome asterisks.” The sea urchins in this poem quite literally inhabit the footnotes, existing below the feet of unfortunate individuals vulnerable to their punctures. In addition, the urchins themselves resemble asterisks (*). Second, “Their extraneous / complaints are lodged with dark dots, / subcutaneous / ellipses…” The wounds the sea urchins inflict on these feet, “soft underbellies,” resemble ellipses (…). Stallings uses typographical marks in order to detail a picture of sea urchins and the injuries they inscribe on human feet. This use of typography clues us into Stallings’ intellectual playfulness in the poems of Like.

Aside from her pivotal piece, “Like, the Sestina,” Stallings’ recurrent theme of human love shows itself most clearly in her poems about the refugee crisis in Greece, the result of natural disasters and war in surrounding countries, most significantly the Syrian Civil War. “Empathy” develops an analogue between Stallings’ family and an unnamed refugee family. The speaker says:

My love, I’m grateful tonight

Our listing bed isn’t a raft

Precariously adrift

As we dodge the coast guard light,

And clasp hold of a girl and a boy.

The analogue continues through the poem, depending on verbs whose actions are negated. The reason for this comparison makes more sense upon reading the final quatrain:

Empathy isn’t generous,

It’s selfish. It’s not being nice

To say I would pay any price

Not to be those who’d die to be us.

Empathy does not constitute love according to Stallings, who volunteers to assist refugees at asylums in Athens. Love is much more than imaginative solidarity with the feelings of sufferers. It also involves active attention and care. Love involves emotions, but it is not limited to them. Love cannot exist in a state of inertia, as Christ Himself showed us in the Incarnation, His ministry, His death, and His resurrection.

The latter poem, “Refugee Fugue,” resembles the musical composition. Like a fugue, a central melody interweaves through multiple parts: the lack of love in the humanitarian crisis. The first part, ‘Aegean Blues,’ paints us a picture of the sea—the place “where some swim, and others drown.” The second part, ‘Charon,’ shows us, by using the image of the underworld ferryman, the profit people gain from the suffering and loss of these refugees. The third part, ‘Aegean Epigrams,’ a series of short, rhymed mini-poems, continues and complicates what the previous parts have brought to the surface. The final part of this poem, ‘Appendix A: Useful Phrases in Arabic, Farsi/Dari, and Greek,’ presents a list of words (in English) that volunteers should know when working with refugees, ending in the deadening, unlovely, “Next person.” This last word on the list shows the lack of love in the customhouses for those seeking refuge. People are quicker to move on to the “next person” than to love the person in front of them.

In both of these poems, Stallings alerts the reader to the scarcity of love in the world, specifically in the refugee crisis. In these poems, more pointedly in “Refugee Fugue,” Stallings’ tragicomic voice silences its humor and becomes frighteningly sincere. Stallings seeks to awaken the human capacity for love by showing us the lack of it in both the ancient and contemporary worlds.

I leave my reading of Like reflecting on the love Stallings concerns herself with. Even more, I leave my reading of this collection contemplating Love Himself, the Love we issue from. This Love is the love of God, from which all other loves flow. This Love is not merely humanitarian, yet so concerned with individual humans and all of humanity. This love is beyond humanitarian efforts, yet it does not exclude them. It is the Love of Jesus Christ itself. It is the self-sacrificial Love of the Savior who gives up all of Himself for the sake of His people. This Love is the fullness of Love itself, the fullness of Love Himself.

In Like, Stallings crafts witty and masterful poems in both traditional and created forms. Never giving into humor gratuitously, nor taking her concerns too seriously, she balances between the tragic and the comic in order to propose a robust and realistic vision for love in this world. Readers are bound to “Click Like”—as I do.

JOEY JEKEL works for Reformed University Fellowship (RUF) at The University of Alabama as a campus intern. He attended The Cambridge School of Dallas, a classical Christian high school in Dallas, TX, and studied English Creative Writing, Philosophy, and Classical Studies at The University of Arkansas.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply