This one comes to us from our friend Jason Micheli.

I’ve grown wary of the Christmas “tradition” of bemoaning the commercialization of Christmas in our culture.

I’ve grown wary of the Christmas “tradition” of bemoaning the commercialization of Christmas in our culture.

Too often, we begin Advent not with Isaiah’s laments or John the Baptist’s words of judgment but our own words of lament and judgment, criticizing others for being so materialistic about Christmas.

And, of course, like all cliches, there’s truth to the complaint about consumerism. Like all traditions, there’s a reason we’ve made it a tradition to lament and judge what commercialization has done to Christmas.

Consider: the average person last year spent $1,000 at Christmas. And maybe some of the complaining we’re doing at Christmastime is actually self-loathing because apparently over 15% of all the money we spend at Christmas we spend on ourselves. We don’t trust our wives to get us the gift we really want so we buy it for ourselves.

It’s true—we spend a lot at Christmas. Very often money we don’t have.

In 2004, the average American’s credit card debt was $5,000. Now, it’s $16,000. Retail stores make 50% of their annual revenue during the Christmas season, which I can’t begrudge since my church brings in nearly 50% of its budget during the Christmas season.

We spend a lot at Christmas. But we give a lot at Christmas.

And we worry and we fight a lot at Christmas too. Everyone knows the Christmas season every year sees a spike in suicides and depression and domestic abuse. We not only make resolutions coming out of Christmas, we make appointments with AA and therapists and divorce lawyers too.

So the reason that complaining about consumerism at Christmas has become a Christmas tradition is because there’s some serious, repentance-worthy truth to it.

The problem, though, in critiquing how our culture has co-opted Christmas is that it’s too simple a story; that is, the critique itself is much older than our current situation.

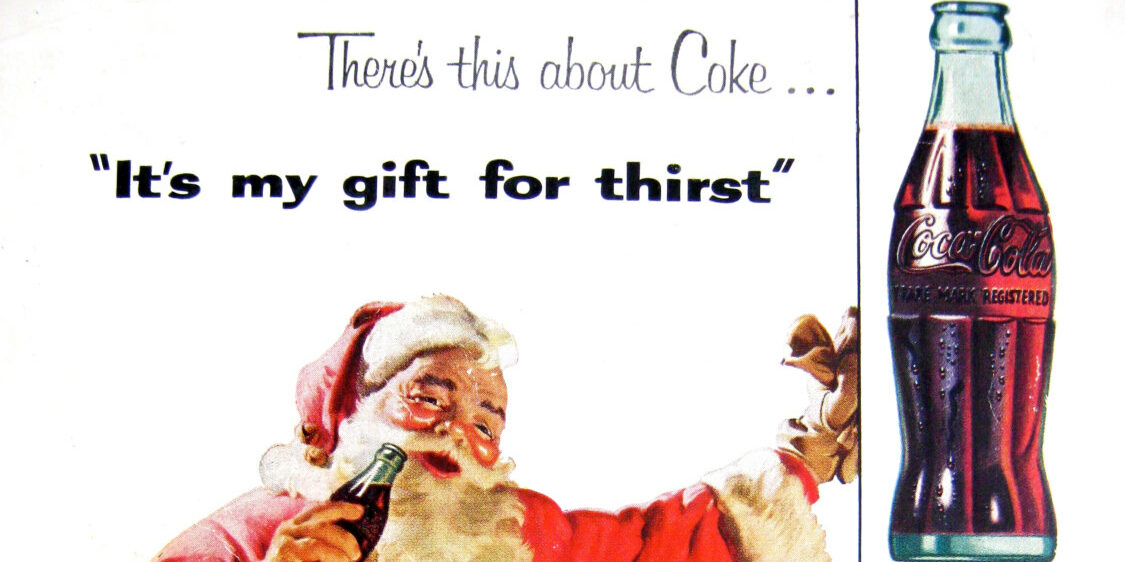

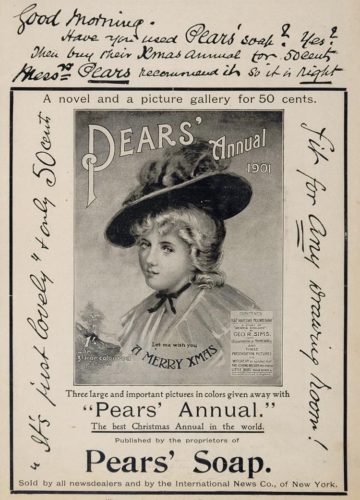

Even before Amazon and Black Friday, people were shopping and putting their kids on Santa’s lap to beg for stuff. Don’t forget—the holiday classic Miracle on 34th Street, it’s a Christmas movie about a shopping mall. The original version of that movie was filmed way back in 1947. Advertisers were using images of St. Nick to sell stuff at least as far back as 1830, and Christians were complaining about it then too, probably as they purchased whatever products Santa was hawking. In 1850, Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, wrote a story called “Christmas” wherein the main character gripes, “Christmas is coming in a fortnight, and I have got to think up presents for everybody! Dear me, it’s so tedious and wasteful!” To which, her Aunt responds, “…when I was a girl presents did not fly about as they do now. Christmas was more spiritual and less materialistic when I was a girl.”

According to Ronald Hutton, in his book The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain, the commercialization of Christmas is the fault of Victorian culture. However, he notes, this is an ambivalent history, because prior to the Victorian era, Christmas was celebrated exclusively by the rich. In other words, the Victorian commercialization of Christmas we abhor was actually an attempt to make Christmas available to the poor and the not-rich.

In the vein of “everything new is old,” Hutton cites diary entries as far back as 1600 describing Christians’ habits of spending and gift-giving, but also their complaints about the rising costs of Christmas meals, Christmas entertainment, and Christmas gifts. Bemoaning what we’ve done to the Christmas tradition is a Christmas tradition at least 400 years old, leading me to wonder if the Magi spent their trip back from Bethlehem complaining about the cost of the myrrh.

We’ve been spending too much at Christmas, and feeling guilty about it, and judging others for it, for a long, long time.

So, if you want to continue that tradition by, say, participating in the Wise Men Gifts Program (where your kid only gets three presents), go for it.

I mean, I would’ve hated my mom if I’d only gotten three presents as a kid, and it’s a good thing I didn’t grow up a Christian because I probably would’ve hated Jesus for it too. But go for it, maybe your kids are better than me. Or, buy an animal in honor of a loved one through our Alternative Gift Giving Program. But, a word to the wise. Learn from my mistake: if you buy an Alternative Gift for your wife, don’t make it a cow. Or, you could join up with the Canadian Mennonites who started the Buy Nothing Christmas Campaign back in 1968. A noble goal to be sure, but, you know as well as I do, those Canuck Mennonites are probably zero-fun killjoys to be around at Christmas.

Knowing that the commercialization of Christmas, our participation in it, and our complaints about it after the fact go back further than America, gives me two cautions about trying to simplify and get back to the “spirit” of Christmas.

First, I worry that, in trying to avoid the excess and extravagance of the season and in exhorting others to go and do likewise, Christians at Christmas sound more like Judas than Jesus.

“We could’ve sold that expensive perfume and given the money to the poor!” Judas complains about Mary anointing Jesus.

“I’m worth it,” Jesus pretty much says.

“You won’t always have me [or the people in your lives]. There will be plenty of opportunity to give to the poor.”

In a culture where many Americans associate Christianity with judgmentalism and self-righteousness, sounding more like Judas than Jesus is more problematic than our credit card bill, I’d say. And obviously we do spend too much. But ‘Why do we?’ is the better question.

And that gets to my second caution: I worry that the imperatives to spend less money and get more “spiritual” make it sound too easy. I worry, in other words, that they rely upon a more optimistic view of our human moral capacity than scripture gives us.

Here’s what I mean. Take this statistic: 93%. That’s the percentage of Americans who believe that Christmas has become too commercial and consumer-driven. Not only is lamenting the commercialism of Christmas neither new nor prophetic; no one disagrees. Everyone agrees we spend too much money on too much junk at Christmas. But we do it anyway.

Forget Isaiah and John the Baptist, Romans 7 is what we should be reading during Advent:

“I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate … I can will what is right, but I cannot do it. For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I do.”

“Thou shalt” provokes “I shall not.” Me exhorting you, then, or the Church exhorting the culture, to spend less money and get more “spiritual” at Christmas will not only fail, it will prove counter-productive because, as Paul Zahl paraphrases St. Paul here, “Ceaseless censure produces recidivism.” Thus, it’s not surprising we’ve been bemoaning the commercialization of Christmas for going on five centuries but to no avail. That’s the Law. And the Law, Paul says, is inscribed upon every human heart (Rom 2:15).

So even if you don’t believe in God or follow Jesus or read the Bible, the capital-L Law manifests itself in all the little-l laws in your life, all the shoulds and musts and oughts you hear constantly in the back of your mind, all those expectations and demands and obligations you feel bearing down on you from our culture.

And Christmastime comes with Law all its own. At Christmastime, there’s the Law of Pinterest that tells you you must have new adorable matching clothes for your kids for the Christmas Letter photo or you’re a failure as a woman.

Speaking of which, there’s the Law of the Christmas Letter, which is a hard copy version of the Law of Social Media, which says you must crop out all your unhappiness and imperfection.

There’s the Law of Manhood, which tells you you should earn enough money to buy your family the gifts they want.

There’s the Law of Motherhood that tells you you must wrap all the presents perfectly, valued at at least what your sister-in-law will spend on her kids, you must make homemade holiday cookies like you think your mother used to do, and you must find time to spend “quality time” with your kids or you’re no better than Ms. Hannigan in Annie.

And there’s the Law we lay down, the Church, telling people they should have a holy, meaningful, spiritual experience at Christmas whilst doing all of the above and table-scaping a Normal Rockwell dinner, not forgetting the less fortunate and always remembering that Jesus is the reason for the season.

Piece of cake, right?

The Law always accuses.

That’s its God-given purpose, says the Apostle Paul, to accuse us, to point out our shortcomings and reveal where we fail to be loving and kind and generous, where we fail to be good neighbors and parents and spouses and disciples.

When it comes to Christmas, the Church and the culture do what AA tells people not to do: they “should” all over people.

That’s why Christmas is such a powder keg of stress and guilt.

We’re being accused from all angles by the Law:

For who we are not.

How we fall short.

What our family and our Christmas isn’t.

That’s why we can all agree we shouldn’t spend so much at Christmas but we do anyway. We’re bound to the Law, St. Paul says. And it’s the nature of the Law to produce the opposite of its intent; so that, what we do not want to do (overspend) is exactly what we do. And that’s why our spending coincides with such sadness. We’re prisoners to the Law. We’ve been accused and have fallen short.

When I tell you, then, how you should spend, you might applaud or nod your heads but, truthfully, it would just burden you with more Law.

When I tell you, then, how you should spend, you might applaud or nod your heads but, truthfully, it would just burden you with more Law.

The Apostle Paul says the purpose of the Law is to shut all our mouths up in the knowledge that not one of us is righteous, so that then we can receive the gift of God in Jesus Christ.

Which is what, exactly?

I mean, we’ve memorized the gifts the Magi give to Jesus, but could you answer just as quickly and specifically if I asked you to name the gift God gives to us in Jesus? We like to say that Jesus is the reason for the season, but I’m not convinced we know the reason for Jesus.

And maybe the problem is that we spend so much time talking about what God takes from us in Jesus Christ that we can’t name what God gives to us in Jesus Christ. And it’s not knowing that gift that makes us vulnerable to such stress and self-righteousness every Christmas season. We spend all our time talking about what God takes from us in Christ—our sin. But our sin isn’t even the whole problem, because even our righteous deeds, says Isaiah, even our good works, even the best possible version of your obituary, is no better than a filthy rag.

The Gospel is incomplete if it doesn’t also include what God gives to us: Christ’s own righteousness.

Christ became our sin, says the Bible, so that we might become his righteousness. His righteousness is given to us as our own righteousness. You see, it’s the original Christmas gift exchange. Our rags for his riches. God takes our filthy rags and puts them on Christ, and God takes Christ’s righteousness and God clothes us in it.

That’s the short, specific answer: righteousness.

The Magi give frankincense, gold, and myrrh to Jesus.

God gives to us, in Jesus, Christ’s own righteousness.

It’s yours for free forever.

By faith.

No amount of shopping will improve upon that gift. And no amount of wasteful, selfish spending can take that gift away from you once it’s yours by faith.

No amount of shopping will improve upon that gift. And no amount of wasteful, selfish spending can take that gift away from you once it’s yours by faith.

Sure, we’re all sin-sick and selfish, and our spending shows it. Obviously, we do not give to the poor like we should, but in Jesus Christ, God became poor not so that we would remember the poor. No, in Jesus Christ, God became poor so that we might have all the riches of his righteousness. As Christ says in one of the Advent Gospel readings, we already have everything we need to meet Christ unafraid when he comes again at the Second Advent.

We’ve already been given the gift of his righteousness.

Once you understand this gift God gives to us in Jesus Christ, it frees you, the Bible says. It frees you from the burden of expectations.

Until you understand the gift God gives us in Christ, you’ll always approach Christmas from the perspective of the Law.

You’ll worry there’s a more “spiritual” way that you should celebrate the season, as a Christian. You’ll think there’s a certain kind of gift you ought to give, as a Christian. You’ll stress that there’s a spending limit you must not exceed, as a Christian.

Hear the good news: You have no Christian obligations at Christmas because the gift God has already given you by faith is Christ’s perfect righteousness. The Gospel declares that, no matter what your credit card bill or charitable contribution statement says, you are righteous. You are as righteous as Jesus Christ because, through your baptism, by faith, you have been clothed in his own righteousness. The gift God has given to you, it frees you from asking, “What should I spend at Christmas?” This gift of Christ’s own righteousness, it frees you to ask, “What do I want to spend at Christmas, now that I’m free to spend as much or as little as I want?”

You see, despite all the Heifer Projects and holiday hashtags, the Gospel frees you to be materialistic—in the way God is materialistic. Because that is how God spent the first Christmas.

The incarnation isn’t spiritual. The incarnation, God taking material flesh and living a life like ours, amidst all the material stuff of everyday life, is the most materialistic thing of all. Christians come by the gift-giving tradition honestly.

If Jesus is “God-with-us,” then giving material gifts of love that highlight our with-ness, our connection to someone we love, really is the most theologically cogent way of marking Christ’s birth.

It’s not that spending money you don’t have makes you unrighteous. God’s already given Christ’s righteousness to you. That can’t be undone.

It’s not that spending money you don’t have makes you unrighteous. God’s already given Christ’s righteousness to you. That can’t be undone.

It’s not that overspending at Christmas is unrighteous; it’s just unwise.

So, don’t buy junk for the sake of buying junk.

But if you’ve got the money, then maybe the most Christian thing to do this Christmas is to buy someone you love the perfect present.

Because God got materialistic on the first Christmas in order to give you the gift of Christ’s perfect righteousness.

Maybe materialism—in the freedom of the Gospel and not under the burden of the Law—is exactly what Christians need to put Christ back in Christmas.

COMMENTS

3 responses to “Why You Should Spend Whatever You Like Buying Friends and Loved Ones Gifts They Don’t Expect (and Don’t Deserve)”

Leave a Reply

Hot diggity dawg, I had no idea I would tune in this morning and get rocked by this salvo of good news. Thank you, Jason— may we all be swept up into the liberating lift of gospel materialism!

You’re most welcome! Thanks for the feedback.

Thank you, Jason – this is the best article on the subject I’ve ever read. Moralism always sounds so pious, but in my experience moralism in the church is the greatest enemy of the Gospel.