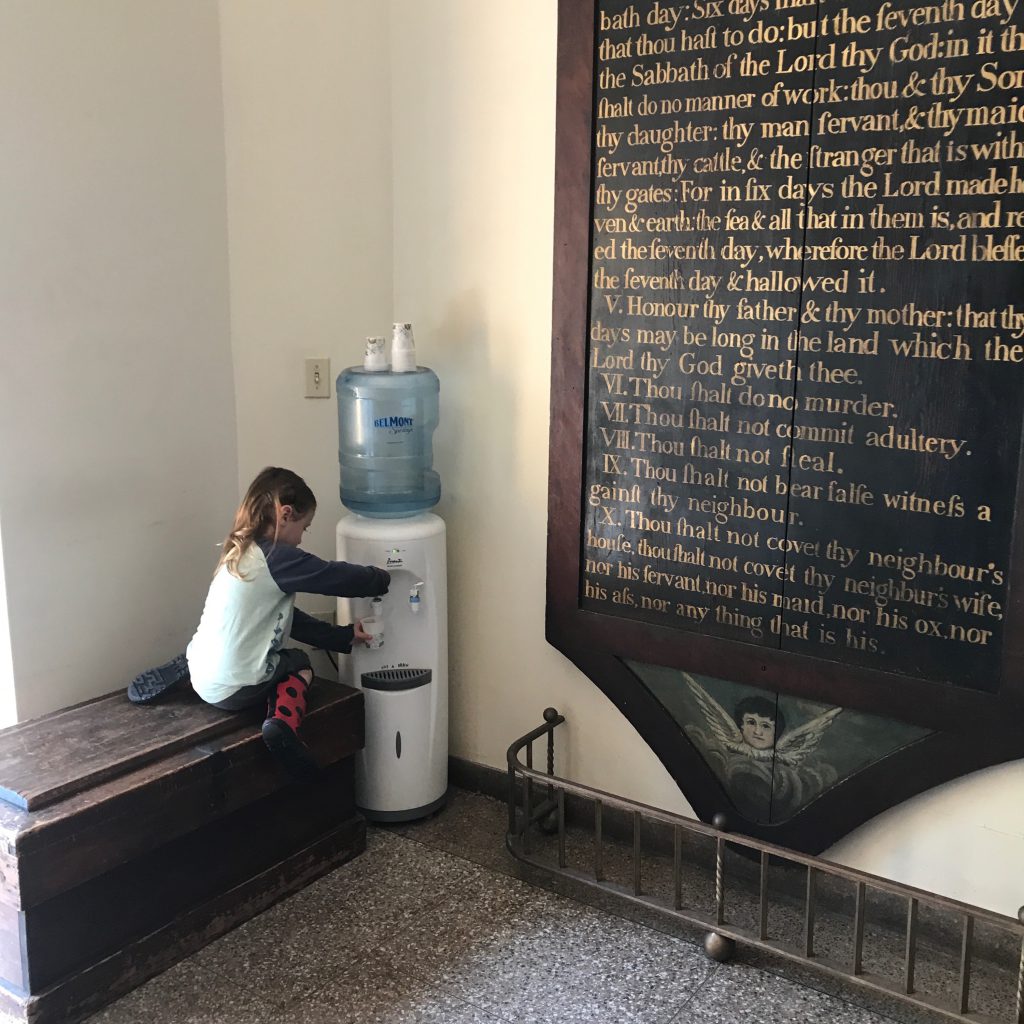

In the narthex of my parish church there is a beautiful monument of American religious art: two ceiling-high wooden tablets, both with gold lettering on a black background. One carries the text of the Ten Commandments. The Apostles’ Creed and the Lord’s Prayer are on the other.

The Law, the Gospel, and the Church’s simplest roadmap of belief are contained here in little space and in one field of vision.

This is a frequent element of protestant Anglican church adornment, usually fixed on the eastern wall where all can see it: text-based, instructive, non-debatable, leveling of cleric and squire before the same authority, edifying in the sense of building-up, informing, strengthening, focused on literacy and understanding. This is familiar enough in English churches of a certain architectural vintage, and in the places they influenced through empire—though on these American shores primarily from Virginia through Massachusetts and New Hampshire, and not usually later than about 1830.

Our tablets are different than most. Beneath each are the staring faces of impassive angels, gazing back at the viewer in attitudes it is hard to parse. What do their faces mean? Angels are uncommon in this genre—I have never seen their like in a life-time of church-crawling—and some would find the heads of the putti a violation of the injunction against graven images just above them in gilt lettering. But I like the angels, and I usually glance down at them in coming and in going, wondering what they think about my pale shins.

It is now impossible to count the times the tablets in their day threaded scripture and prayer through the understanding vision of believers at services of Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer, or quarterly and then monthly Holy Communion. But I know the number—counted against the background of New England’s muds and times and seasons—would be staggering. They are the painted, wooden traces of tens of thousands of hearts lifted and given to God, transformed by his grace in word and sacrament, grafted onto the living tree of bold souls who can pray “Our Father.”

The tablets have moved at least twice since their installation at Trinity in 1803. They went to nearby Christ Church, Bethany in 1816 when our new building was completed, and they were returned in 1885 for reasons that are obscure. I do not know when they ceased to be a visual aid to worship in the main body of a church. And still I am forced to think against my own aesthetic preferences that they were the highly effective overhead projectors of their day.

The tablets’ current location—on the left (north) side of the entryway—has seemed strange to me, because worshippers have no reason to pause in the narthex of a Sunday unless we’re late and must wait for the procession to reach the chancel before we proceed to our galleries and box-pews or the undercroft. If we’re on time, we breeze past the tablets to get a service leaflet from a friendly usher, paying no mind to the underfoot gazes of the cherubim or the blazing, holy words above them and us.

I have sometimes been put in mind of the apocryphal nineteenth-century bishop who objected to the use of a processional cross, and the choir who then sang

Onward, Christian soldiers, marching as to war;

With the Cross of Jesus, hung behind the door.

Last Saturday, a routine errand brought me to church with my daughters on a muggy afternoon, and something fresh clicked.

“Papa, I can have some water?” said-asked my little Elisabeth, whose voice is an incessant piccolo each day from 5:00 a.m. to 7:30 p.m. (She is very excited to turn four.)

“Of course you can have some water, Ella!”

Ella had seen the water cooler in the corner next to the tablets—a source of refreshment I had not noticed in a week of years of walking through this space. The liturgical scholar, the church historian, the local architecture buff I am had overlooked the tablets as witnesses in the regular fulfilling of that old and easy line from the Gospel of Matthew:

Ella had seen the water cooler in the corner next to the tablets—a source of refreshment I had not noticed in a week of years of walking through this space. The liturgical scholar, the church historian, the local architecture buff I am had overlooked the tablets as witnesses in the regular fulfilling of that old and easy line from the Gospel of Matthew:

And whosoever shall give to drink unto one of these little ones a cup of cold water […] verily I say unto you, he shall in no wise lose his reward.

I was blind to the water, the cooling nourishment my pre-reading daughter could see so easily because it was just what she wanted. She could see what she needed, and she asked for it. She could see what we all need, and she asked for it.

I was blind to the weekday ministry of the Water Cooler on the Green, where the poor, homeless, afflicted of my city—to whom we minister in countless other ways that are never enough—can come to drink a cool cup of water before the tablets and the angels, those reminders of God’s presence, love and grace. The church is always open in the daylight, and a happiness welled up in my heart to see that my daughter could see in our community what I did not.

As in so much, I have been taught by my children to look just to the left or just to the right or just below my eye-level to see a bigger picture. Thanks to Elisabeth, I will never walk by the tablets in the same way again. I will now early and often count myself among those who stop to take a little cup of water while reading the words from which once we have sipped we can never thirst—with my girls, in common with our neighbors of every sort and condition—in a place of cool and goodness within a city of heat and of need.

Of course you can have some water, Ella!

Future Islands – Ancient Water (The Far Field Album) (2017)

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply