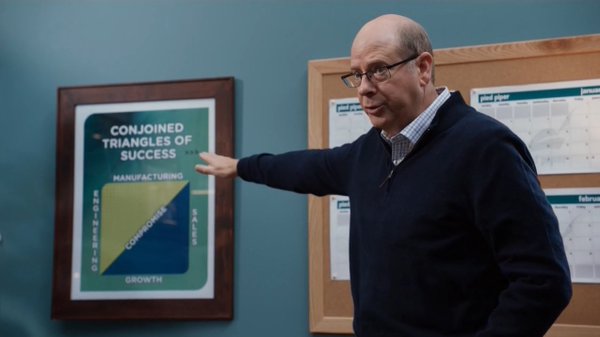

I don’t have to think of a clever lead-in for this post. Erlich Bachmann has me more than covered:

That’s a solid four and half minutes of unaired, improvised, and largely top-drawer old-fogey jokes courtesy of T.J. Miller’s Silicon Valley maestro. As with much of what happens on that show, there’s a biting subtext, in this case the writers hinting at what one publication recently called The Brutal Ageism of Tech.

“Another day, another -ism”, the cynical among us might sigh, and at this point you can’t exactly blame them. A culture of complaint has a way of devaluing grievance, especially when it comes to conventionally “established” identity groups. Plus, isn’t “ageism” just a way of talking about generation gaps, and haven’t the young always scoffed/bristled at the old–and the old always rolled their eyes (and wagged their fingers) at the young?

Yet there’s a difference between generational resentments and actual, active discrimination, and if Ashton Applewhite’s op-ed in this past weekend’s NY Times, “You’re How Old? We’ll Be In Touch”, is to be trusted, we may have crossed into the latter domain. That is, while the rest of the country may not have reached the cartoonish levels in evidence on the West Coast, the effects of our longtime cultural preference for all things youthful may have turned inescapably tangible.

According to Mr. Applewhite (!), far from being the boon it once was, ‘experience’ is now being held against more and more applicants in the job market. It’s not just that the over-the-hill delineation has plunged steadily downward but that the locus of power has shifted along with it. Or so it would appear. (What about all those reports about young people growing up later? Taking longer and longer to establish economic and social wherewithal/capital? Hmmm…)

Anyway, after debunking several of the conventional rationalizations for age stratification in the workplace, Applewhite comes to a telling conclusion:

“Culture fit” gets bandied about in this context — the idea that people in an organization should share attitudes, backgrounds and working styles. That can mean rejecting people who “aren’t like us.” Age, however, is a far less reliable indicator of shared values or interests than class, gender, race or income level. Discomfort at reaching across an age gap is one of the sorry consequences of living in a profoundly age-segregated society. The Cornell gerontologist Karl Pillemer says that Americans are more likely to have a friend of a different race than one who is 10 years older or younger than they are.

Age segregation impoverishes us, because it cuts us off from most of humanity and because the exchange of skills and stories across generations is the natural order of things. In the United States, ageism has subverted it…

It may not be as sexy (…) or expedient as some of the other ‘isms’ out there, but mark my words, we’ll be hearing a lot more about ageism in coming years, for the simple reason that, to the extent that it’s real, all of us will soon be its victim. He goes on to say as much:

Confronting ageism means making friends of all ages. It means pointing out bias when you encounter it (when everyone at a meeting is the same age, for example).

Confronting ageism means joining forces. It means seeing older people not as alien and “other,” but as us — future us, that is.

I’m tempted to go on a rant here about the American church and the sad juvenilization (i.e., sub out “meeting” for “worship service”) that has led us further away from the reality of death and into a love affair with works/ethics/living, sidelining the gospel of salvation. But that post has already been written. And besides, if what Applewhite says has merit, then the church can only benefit, its essential counter-culture less a liability with each passing day. That is, where daily existence seems to only becoming more mediated and intangible–entire modes of communication themselves strictly segregated by age–the church stands as a bastion of embodied all-ages community.

What interests me here is less the merits of Applewhite’s particular claim re: ageism and more the reminder that compassion is a frustratingly finite resource: the more you exercise in one area, the less seems to be available in others. Or, the more “inclusive” we believe ourselves to be in one arena (income, sexuality, race, etc), the easier it is to justify opposing attitudes in others (age, political persuasion, body type, religion)–what Malcolm Gladwell calls moral licensing. Such is the human propensity for self-justification that what looks like progress invariably hides a reorganization of prejudice. Yesterday’s underdogs are tomorrow’s overlords and vice versa.

Sounds cynical perhaps, but it’s also comforting–on the level of “this too shall pass” at least. (If you find yourself disenfranchised this decade, just wait.). In his classic adventure novel Allan Quatermain, Rider Haggard put it this way:

“Man’s cleverness is almost indefinite, and stretches like an elastic band, but human nature is like an iron ring. You can go round and round it, you can polish it highly, you can even flatten it a little on one side, whereby you will make it bulge out the other, but you will never, while the world endures and man is man, increase its total circumference.”

Law is the air such constrained creatures breathe, both individually and collectively. The spectrums of deserving we erect all but dictate that one identity group will end up on the outcast or ‘less-than’ side of the equation. The poor we will always have with us, but the parameters of that designation are fluid and will vary according to cultural and political mores. What we ultimately need, therefore, is not a new or updated scaffolding of deserving but a wrecking ball of grace. True compassion, if it is to be genuinely expansive, must be divine.

This has repercussions not merely for those who are called to serve the disenfranchised and downtrodden, but for anyone interested or invested in what Robert Capon means when he writes that “God deals out salvation solely through the klutzes and nobodies of the world – through, in short, the last, the least, the lost, the little, and the dead.” These categories will, by definition, be in tension with whatever cause celebre has us in its thrall, however noble it may be.

Perhaps the temptation to scoff or dismiss a grievance as illegitimate may actually indicate its legitimacy. If not legitimate than certainly holy. After all, the ever-roving blindspot of disgrace doubles as a spotlight for where the gospel never gets, well, old.

Blessed are the unromanticizable. You, in other words.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply