This one comes to us from Lindsey Hepler.

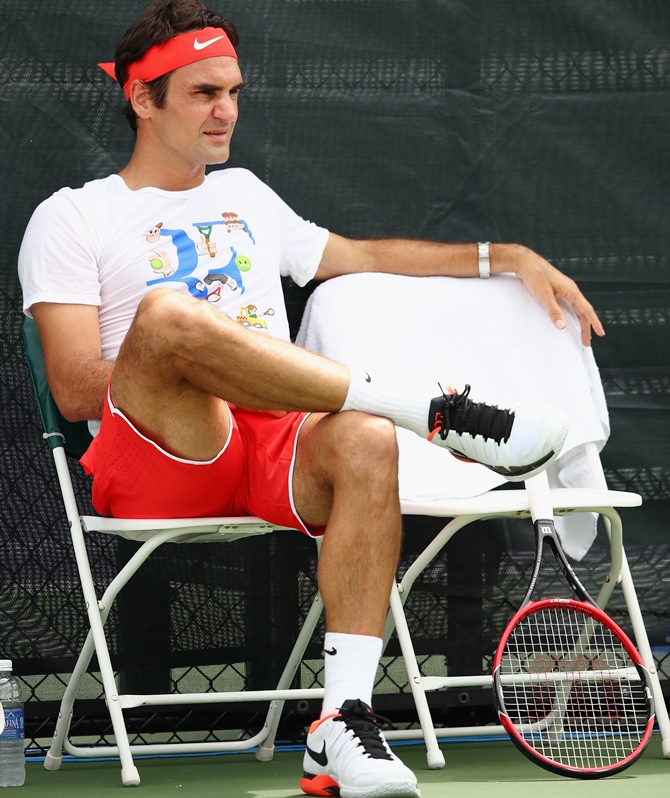

When I was eighteen years old, during that awkward summer between graduating from high school and starting college, I took a trip to London with my parents. By a stroke of luck and happenstance, my two sisters were away on their own adventures, so I got to be the only child for a week. It was a fantastic trip—complete with a 24 hour jaunt to Paris, a meal so memorable, I still think about it, and two days at Wimbeldon—for the men’s and women’s finals, no less. My parents are avid tennis players, and this trip to Wimbeldon had been a long-time dream of theirs. I was just along for the ride. But there is something about Wimbledon that can make a convert out of even the most uninformed attendee. The British charm; the all-white attire; the grass courts; the champagne and strawberries; the superb levels of athleticism on display. The pomp of it all was intoxicating. So there I was, trailing behind my father as we made our way through the crowds towards the marquise (fancy British word for “tent”, except this tent had a chandelier hanging in the middle of it, and a waiter in coat and tails greeted me with a glass of champagne when we got there) for lunch, when I heard my mom behind me, whisper-shouting at me to stop. I turned around to see what the fuss was about, and she was pointing to the practice court we were walking alongside, whisper-shouting, “That’s Federer!” Now, as I said, I knew very little about tennis at that point in my life, but I knew, instantly, that I was in the presence of greatness. As David Foster Wallace wrote in his 2006 essay, “Roger Federer as Religious Experience”:

“A top athlete’s beauty is next to impossible to describe directly. Or to evoke. Federer’s forehand is a great liquid whip, his backhand a one-hander that he can drive flat, load with topspin, or slice — the slice with such snap that the ball turns shapes in the air and skids on the grass to maybe ankle height. His serve has world-class pace and a degree of placement and variety no one else comes close to; the service motion is lithe and uneccentric, distinctive (on TV) only in a certain eel-like all-body snap at the moment of impact. His anticipation and court sense are otherworldly, and his footwork is the best in the game — as a child, he was also a soccer prodigy. All this is true, and yet none of it really explains anything or evokes the experience of watching this man play. Of witnessing, firsthand, the beauty and genius of his game. You more have to come at the aesthetic stuff obliquely, to talk around it, or — as Aquinas did with his own ineffable subject — to try to define it in terms of what it is not.”

The next day, we watched Federer defeat Andy Roddick 6–2, 7–6(7–2), 6–4 in the final to win the Wimbledon title for the third time. I have been a Federer devotee ever since. Even in recent years when Djokovic and Nadal have battled for number 1, my love for Federer, and my belief in his superiority, has never wavered.

I say all of this as a way to preface my interest in an article I read on Sunday, in which Brian Phillips brilliantly articulated the difficulty of watching that same god-like, seemingly superhuman Federer sit out for most of this season due to a knee injury (a knee injury that he incurred while giving his daughters a bath). Referring to the DFW essay I quoted from above, Phillips explains that Wallace’s essay “did more to construct the terms in which we now view Federer than any other. Wallace advances the impossibly ambitious, totally doomed and thrillingly beautiful idea that high-level spectator sports serve an aesthetic and even quasi-spiritual function, namely to reconcile viewers to the limitations of their own bodies. The body ages, breaks down, gets sick, suffers and dies. But when we watch Federer in peak moments, Wallace says, we imagine what it would be like to experience a physical freedom unburdened by pain or weakness, and this in turn helps us cope with the troubling fact of our own mortal embodiment.”

I say all of this as a way to preface my interest in an article I read on Sunday, in which Brian Phillips brilliantly articulated the difficulty of watching that same god-like, seemingly superhuman Federer sit out for most of this season due to a knee injury (a knee injury that he incurred while giving his daughters a bath). Referring to the DFW essay I quoted from above, Phillips explains that Wallace’s essay “did more to construct the terms in which we now view Federer than any other. Wallace advances the impossibly ambitious, totally doomed and thrillingly beautiful idea that high-level spectator sports serve an aesthetic and even quasi-spiritual function, namely to reconcile viewers to the limitations of their own bodies. The body ages, breaks down, gets sick, suffers and dies. But when we watch Federer in peak moments, Wallace says, we imagine what it would be like to experience a physical freedom unburdened by pain or weakness, and this in turn helps us cope with the troubling fact of our own mortal embodiment.”

After I read the article, I pushed my stiff and aching body—I had just finished my first yoga class in over a week, and sitting in an air-conditioned house was taking a toll on my no-longer-warm-and-pliable muscles—up out of my chair, acutely feeling the accuracy of that last statement about “the troubling fact of our own mortal embodiment.” There’s no denying the reality of aging, and the slow process by which our bodies deteriorate. Each new ache or pain, each new wrinkle, is a constant reminder that we are, ultimately, headed to the grave.

Towards the end of the article, Phillips takes an interesting turn, a turn that points out the clear problem with making a God (i.e. an idol) out of a mortal human-being:

“It seems poignant, to me at least, that an essay depicting Federer as transcending the body and a commercial depicting Federer as transcending time should pass across the tennis world’s news feed at a moment when the real Federer is home with an injury. And not just an injury — an old-person injury, a dad injury. Federer’s dark post-bathtime of the soul feels different from the typical sports layoff, I think, because it brings to the surface a tension that’s been seeping into his persona for a few years now: How do you square the image of the transcendent, unchanging champion with the fact of a player who is growing old?…The Federer of Wallace’s essay can be a transcendent player forever. But the real Federer is made of nothing but flesh, and I can’t help but wonder how we’re going to absorb that news when it finally becomes unmistakable. When the athlete who reconciles us to our failing bodies watches his own body fail — what’s supposed to reconcile us to that?”

Of course I share this lament over the loss of Federer’s reign. Of course I want my Tennis God to continue to rule the court in perpetuity. Of course I want to see perfection embodied, to see a body seemingly defy the laws of physics. And yet, I know that it is not Federer who can reconcile us to our failing bodies.

No, I know that there is One who has already done that work. And thank goodness for it.

Thank goodness I can laugh at my own stiff and aching muscles. Thank goodness I can smile at Federer’s “dad injury”, feeling happy for his transition from Tennis God to Aging Dad. Thank goodness for the One who took on mortal flesh, the One whose failing body hung upon a cross, the One who died that we might live.

COMMENTS

3 responses to “Tennis Gods and Failing Bodies”

Leave a Reply

Beautiful. Long live the Fed!

Beautiful and humbling. Thank you for this post.

I’ve always been a bigger fan of the pure base-liners (Chang, Agassi, Nadal) but Federer’s game will always be the “most complete” of all time.

Such a great piece here. It really is athletic prowess and it’s decline to earthly tent-ness that reminds us best of our fragility and gives us a longing for something/someone that can make us whole again……