As November’s approach continues to dominate the news cycle, the social science research coming out of the election continues to challenge. Chief among the targets of social science research is the enlightenment cornerstone that human beings are functionally rational creatures. The data is suggesting that this cycle we’re all voting out of anger, spite, fear, or some other passion, even if the outward justification for those votes is thoughtful policy evaluation.

Now we have a new motivation to the list: voting by justification. Just kidding about the “new” part–self-justification has “never not” been a motivation for human behavior. As WaPo’s Wonkblog reported last week, new research suggests that when morality is imputed to our decision making, we’re significantly less open to change. When our decisions or beliefs are declared to be moral or upright, we hold them even tighter. It’s imputed righteousness- credit for believing correctly. That’s not really news, per se, but it certainly impacts how we understand this (and every?) election cycle.

The group’s consensus: Recycling is generally a good thing. After respondents wrote down their individual thoughts and took the same nine-point tests, they received feedback on their recycling beliefs. Some heard their views were “practical.” Others heard “moral.”

Then the researchers tried to change everyone’s mind. They slipped respondents a note that said recycling puts more cars on the road and encourages pollution.

People’s attitudes in the “morality” group and “practicality” group didn’t significantly differ before they read the anti-recycling message. But afterward, a post-test revealed the “moral” respondents viewed recycling more favorably (7.56 on a nine-point scale) than the “practical” respondents (6.88).

“Those led to believe that their recycling attitudes were grounded in morality were more resistant to the anti-recycling message than those led to believe that their attitudes were grounded in practicality,” the authors wrote.

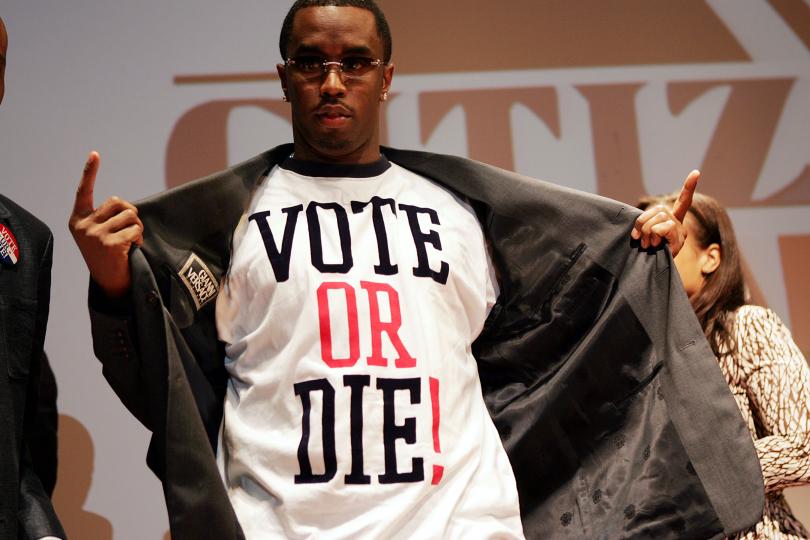

The takeaway, according to Luttrell: Framing a cause as “moral” is a smart tactic for politicians and advocates. Any issue, it appears, can be viewed through the morality lens, which is why we’ll be probably fighting about politics forever.

The study’s great insight isn’t that we hold fast to moral decisions–you don’t need a PhD in sociology to get that. The insight is that when we are viewed as moral for our decisions, we hold them closer. It’s not just personal feelings of morality that impact our vote, it’s the perception of morality among our peers. Who wants to be seen as a flip-flopper on issues of morality (remember Kerry in 2004)?

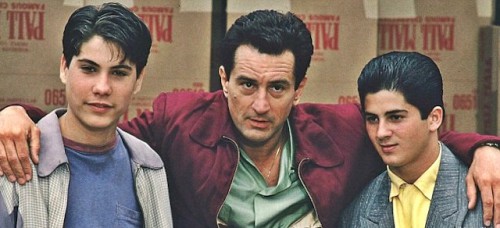

I was in seminary the first time I watched Scorsese’s Goodfellas, and the movie’s early courtroom scene was eye-opening. A young teenager learning the ropes of mob life, Henry is pinched (arrested) for selling stolen cigarettes out of the trunk of a car. The mob comes to his rescue, and with lawyer and judge in their pocket, Henry gets off without any issues. As mob mentor Jimmy comes to Henry after the trial, he imbues the day’s proceedings with moral weight:

I’m not mad; I’m proud of you. You took your first pinch like a man and you learn two great things in your life. Look at me, never rat on your friends and always keep your mouth shut.

As Henry met the cheering mob outside of the courtroom, a fellow seminarian turned to me and wisely quipped, “If I’d had that much male affirmation when I was his age, I’d have joined the mob, too.” It’s potent stuff, and the rest of the movie is Henry wrestling with the irony that these immoral mobsters dole out moral affirmation alongside the cash and community.

To quote pop-philosopher Selena Gomez, “The heart wants what it wants.” Or, to remember Jonathan Haidt’s wisdom from our still relevant 2012 Surviving November series, we’re less the captains of our own USS Enterprise and more of the rider on a stampeding elephant. Or, to even out the political metaphor, riding an unbroken donkey. The power of being perceived as being righteous within the community overrides the work of the will and the mind.

Interestingly, Jesus doesn’t often use the tactic himself–in fact, he’s often busy trying to undo the damage that moral affirmation has already caused. After all, the devout religious community of Jesus’s day would dole out moral affirmation for a myriad of unbiblical ideals, some racist, nationalist, or just downright hypocritical (see, for example, Jesus’s critiques on giving and fasting). Imagine the fallout for Nicodemus had he been caught meeting Jesus for a midnight lesson. In fact, the only folks to receive moral affirmation from Jesus where the folks most undeserving–a pagan soldier, unclean women, a tax collector. It’s all bass-ackwards in Jesus’s world.

In a world where we’ve jokingly imbued the correct toilet paper orientation with moral importance, it’s no surprise that that the political tool of moral righteousness is wielded so effectively. If you’ve got a good way to de-claw a sticky issue by deeming it amoral, feel free to share below. I certainly haven’t figured it out. But at least, in the eyes of heaven, there’s forgiveness and the reconciliation of moral trespasses. Someone had to bleed for it, but it’s there, nonetheless. No matter how many times you’ve been pinched. Bass-ackwards indeed.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply