During a 1995 interview with NPR’s Terry Gross, Pat Conroy related a story about his father, Don, that epitomized the patriarch’s delusional view of identity. The two men were discussing why Pat’s mother left Don when the elder Conroy broke down sobbing. Thinking that Don had finally realized the error of the ways, Pat quoted the ensuing conversation to Gross: “‘Dad, do you understand what you did wrong?’ And Dad said, ‘Yes.’ And I said, ‘What is it, Dad? What did you do wrong?’ And my father said, ‘I was too good. I didn’t crack down hard enough. I was too easy on your mother and my children.’” Pat was able to laugh at the preposterousness of this conclusion–Don had been a horribly abusive father and husband–because of the passage of time and work of redemption. He and Gross laughed over the memory, and so did I, until I stopped short, realizing how often I embody the elder Conroy’s self-deception when it comes to who I secretly think I am.

During a 1995 interview with NPR’s Terry Gross, Pat Conroy related a story about his father, Don, that epitomized the patriarch’s delusional view of identity. The two men were discussing why Pat’s mother left Don when the elder Conroy broke down sobbing. Thinking that Don had finally realized the error of the ways, Pat quoted the ensuing conversation to Gross: “‘Dad, do you understand what you did wrong?’ And Dad said, ‘Yes.’ And I said, ‘What is it, Dad? What did you do wrong?’ And my father said, ‘I was too good. I didn’t crack down hard enough. I was too easy on your mother and my children.’” Pat was able to laugh at the preposterousness of this conclusion–Don had been a horribly abusive father and husband–because of the passage of time and work of redemption. He and Gross laughed over the memory, and so did I, until I stopped short, realizing how often I embody the elder Conroy’s self-deception when it comes to who I secretly think I am.

Lying to ourselves is so easy. We are citizens, after all, of a culture that has perfected performancism to an art form–even providing handy filters so that our self-promotion (or protection?) is caught in the best light! (And yes, before you ask: I am on Instagram.) Our social media selves are substitutable for our authentic selves, the two conflated by our collective willingness as a society to accept our polished, carefully chosen exteriors as a comprehensive identity. “You show me ‘you,’ I’ll show you ‘me,’” we might as well say with every post, our clicking of the Terms of Agreement for each website including a tacit disavowal of full disclosure. Wasn’t this just an organic next step for a culture all too willing to let t-shirts, bumper stickers, and wall hangings proclaim our deepest beliefs?

Maybe I’m too cynical–and by maybe, I mean without a doubt. After all, when I see a poster that admonishes me to dance like nobody’s watching, or a family reduced to stick figures on the back of a minivan (pets included!) I waver between holding a funeral for the part of me that just died, and committing felony vandalism. I’ve just become way too intimately acquainted with my own sinfulness in recent years (thank you, singleness in New York City, then parenthood) to maintain my formerly-revered license in turd-polishing. Life is more than one thing, and so am I–and the filters ain’t always pretty ones.

It wasn’t always this way. Once upon a time, I was adept at toeing the company/culture line: “I’m okay, you’re okay, we’re all okay.” When my high school English class studied Henley’s “Invictus,” I felt a charge at the last two lines. “I am the master of my fate, I am the captain of my soul,” I read, inwardly cheering at the proclamation of personal control which I often heard reinforced on Sundays by sermons specializing in behavior modification. Not until my own personal control waned, and my own perfect record of law-keeping fell apart, did I begin–or need–to understand that sinfulness is a fact to be faced, not my singular shame to hide.

A friend–the one who wrote about it here–recently recommended to me the film Dirty Filthy Love. Had it been something I’d stumbled across while flipping channels, I likely would have abandoned viewing it after the first five minutes, which were nothing short of excruciating to watch, as Mark, a man with OCD and Tourette syndrome, spends hours facing the monumental task of getting out of bed. I persevered and was met with even more difficulty, because the more I saw of Mark, the more I saw myself in him. As a child, I operated under the delusion that I could control my environment–my safety, my parents’, our family’s health and well-being, various other circumstances–by upholding various rituals, many centered around repeating the same prayers, or replicating gestures, or putting objects in exactly the same place.

A friend–the one who wrote about it here–recently recommended to me the film Dirty Filthy Love. Had it been something I’d stumbled across while flipping channels, I likely would have abandoned viewing it after the first five minutes, which were nothing short of excruciating to watch, as Mark, a man with OCD and Tourette syndrome, spends hours facing the monumental task of getting out of bed. I persevered and was met with even more difficulty, because the more I saw of Mark, the more I saw myself in him. As a child, I operated under the delusion that I could control my environment–my safety, my parents’, our family’s health and well-being, various other circumstances–by upholding various rituals, many centered around repeating the same prayers, or replicating gestures, or putting objects in exactly the same place.

Watching Mark devolve into his own sickness felt like a revisitation of some times I’d rather forget, and it was painful until I remembered a story a friend had told me. Her child had fallen ill with a stomach bug, and my friend had experienced an epiphany while cleaning up the youngster’s puke: This is how Jesus approaches us–by embracing us in our dirtiness. The thought had left me cold, and I didn’t understand why; despite my previously discussed aversion to my kids’ suffering, isn’t it encouraging, uplifting, heartwarming to think of our Savior as so willing to be associated with our grossness?

Watching Mark, I saw the missing piece finally slide into place. The story hadn’t resonated with me because the child, in her sickness, was innocent. But Mark? And me? Well, we’ve got our inborn issues with which to grapple, but we’ve also done plenty to screw up our own lives. And therein lies the real good news, the Gospel truth itself, revealed in a scene in which Mark has allowed his hair to become a mop, his beard a magnet for filth, his fingernails an inch long and black with grime: his friend Charlotte, a sufferer of OCD herself, arrives at his apartment to talk to him and, upon seeing his decrepit state, crosses the room (swiftly, much like the father of the prodigal son, I imagine) and embraces him. Then she bathes him.

This is grace: that I am embraced in my sickness–and my shame. The stuff that isn’t my fault, and especially all the stuff that is.

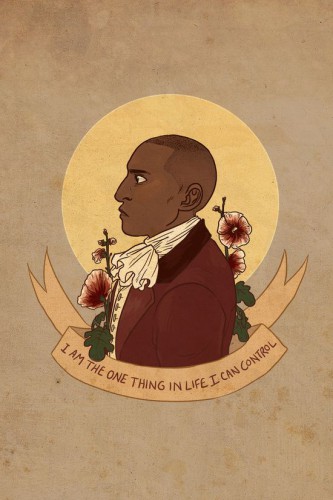

I’m still reeling from seeing Hamilton a month ago, and as the soundtrack resounds throughout our house and car, I find myself analyzing the story afresh with each song. I find the character of Aaron Burr to be particularly compelling, played stunningly by Leslie Odom Jr, because of the villain history has turned him into. But Lin-Manuel Miranda’s version of history doesn’t let simplicity trump nuance; his Aaron Burr is a complicated mass of contradictions: passionate but equivocating; revolutionary but reticent; brilliant but a self-described “damn fool.”

Hamilton may have the show named after him, but in many ways I see Burr as the star: his is the first voice we hear, and it’s his finger that pulls the final trigger. Miranda allows us a window into Burr’s motivation–he speaks of a “legacy to protect” but, perhaps more tellingly and personally, he sings of isolation:

If there’s a reason I’m still alive

When everyone who loves me has died

I’m willing to wait for it.

Later in the song–mixed bag that it is, anthem to both passion and self-protection–Burr sings, “I am the one thing in life I can control.” And I remember Henley’s words about master and captain. I consider the thorn in his own side that Burr saw Hamilton to be this erstwhile partner who constantly seemed to undo and upstage him (I believe the modern term would be frenemies?).

Later in the song–mixed bag that it is, anthem to both passion and self-protection–Burr sings, “I am the one thing in life I can control.” And I remember Henley’s words about master and captain. I consider the thorn in his own side that Burr saw Hamilton to be this erstwhile partner who constantly seemed to undo and upstage him (I believe the modern term would be frenemies?).

I think about my own Hamiltons: the people and circumstances I blame for my undoings, my falls, because it’s easier to find scapegoats than face reality. I’ve blamed enemies, frenemies, even God himself for my setbacks, and if anyone is the “damn fool that shot him” when it comes to our Savior, it is me. And you. Rather than making us the villain of the story, though, that Savior rises up to call us beloved. He crosses the room, the field, the universe, to embrace us in the midst of our Worst Thing–the NSFW content that would get us kicked off Facebook–and suddenly we are disarmed. He is the one Who, finally, sees us. Who tells our story.

And he’s the one who gives us a new song to sing–not of being our own captain, or being in control, but of this:

No guilt in life, no fear in death

This is the power of Christ in me.

From life’s first cry to final breath

Jesus commands my destiny.

This is freedom: for someone else to hold the reins, and me, in his scarred yet perfect hands. When we look at ourselves and finally cry out to him in our full shame, recognizing all that we actually are, his response is, “I AM.” He is everything we are not.

“It will go away if you look at it for what it is,” Charlotte tells Mark, both explaining the mechanism of their disorder and urging him not to pile shame on top of his unchosen infirmities. I’m so thankful that even Disney movies are coming around to what so many of us have been slow to see: in the movie Frozen, Anna sings, “Say goodbye to the pain of the past; we don’t have to feel it any more!” in a winking first-act ode to self-deception that is later upended by reality. Meanwhile, my guilty self knows a past I can’t change and a God who never changes, and the daily liturgy that I read–“O God make speed to save us, O Lord make haste to help us”–reflects my deepest need, true every moment, and met every moment by him.

COMMENTS

3 responses to “Call Me Aaron Burr, Sir”

Leave a Reply

Yes!

“This is grace: that I am embraced in my sickness–and my shame. The stuff that isn’t my fault, and especially all the stuff that is.”……….that’ll just flat preach………ESPECIALLY the stuff that is – so well said Steph……

I don’t know how I’m just stumbling accross this, SP. incredible!!