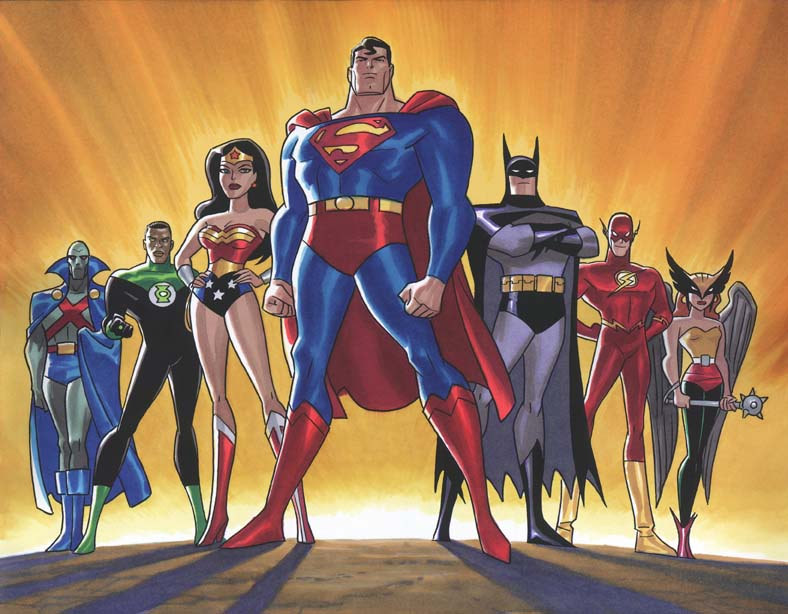

This is the first in a multi-part study (“Justice Has Its Price: The Orphans and Exiles of the Justice League)” on the characters from the cartoon Justice League, brought to you by superhero guru, Wenatchee the Hatchet.

After the Caped Crusader and the Man of Steel have had at least half a dozen movies each, you would think we would have gotten a single live action Wonder Woman film within the 20th century, too, but we didn’t. One of the recurring debates among fans of Wonder Woman has been exactly why this hasn’t happened. Different explanations have been offered as to why. Maybe Wonder Woman doesn’t need a Hollywood treatment to begin with. Then again, some of her fans don’t want her to be a sidekick in a film about Superman and Batman, either. Even Wonder Woman fans have proposed that there are some inherent contradictions in Wonder Woman’s origin myth that are difficult to reconcile: Wonder Woman is a warrior trained to kill who chooses not to kill, for instance.

But the problem is not really that Hollywood isn’t ready for a feminist hero. The problem is deeper; no one has established a reason why American pop culture even needs Wonder Woman in the 21st century. What does she accomplish for us? Being the first woman superhero isn’t enough. Right now we’ve got Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Xena, The Powerpuff Girls, and others. My nieces love Katara, Toph, and even Azula from Avatar: The Last Airbender but have no real use for Wonder Woman. Even if we take Noah Berlatsky at face value about how Marston invented Wonder Woman to be Superman-but-better, she is still essentially the first Mary Sue in the superhero genre.

That’s not a great starting point. Let’s say we grant Steven Grant’s point that the early Superman was “the world’s most altruistic bully, a veritable sovereign power unto himself.” If we think that Superman’s power-altruism would be brutally totalitarian in the real world, let’s remember that Wonder Woman’s magic lasso originally gave her the power to impose her will on everyone she fastened it around. We’re not talking about characters here who could be easily updated to a post-Cold War era of skepticism about American morality and exceptionalism the way Batman has by Christopher Nolan.

What’s more, since the end of World War 2 Superman has become less and less what Steven Grant called “the world’s most altruistic bully” and more like, well, Marston’s Wonder Woman! Arguably Wonder Woman’s influence on comics and superheroes was successful enough that she made herself nearly obsolete in the superhero pantheon. Possibly worse still, unlike Batman, neither Superman nor Wonder Woman is even really human. Superman is an alien from Krypton, and, in folkloric terms, Diana of Paradise Island is basically a golem, a being made of clay brought to life by a god. Golems have not, in global history, had a history of being hugely relatable. But even this is not an insurmountable problem or even the most serious problem in attempting to update Wonder Woman for the 21st century. As we’ve seen, the hurdles in adapting Wonder Woman into a 21st century pop culture are legion in contrast to the Man of Steel and the Dark Knight, whose origins are so skeletal and simple and so anchored to powerful orphans fighting evil in honor of the memory of lost loved ones they have at least a dozen movies between the two of them.

As we attempt to sort through these difficulties faced by those who would bring Wonder Woman to the big screen (or even any screen!) it hardly helps America’s first superheroine that her implacable adversary may be the impossible expectations of her fans. Wonder Woman has to mean too many things to too few people. It’s as though her fans want water to exist as steam and ice simultaneously, and you’d need a water-bender to pull that off. Wonder Woman fans who don’t want Steve Trevor or Etta Candy or the Holiday Girls are basically people who don’t want Wonder Woman at all, just a Superman with ovaries. Wonder Woman has no capacity to be an existential loner. She’s not Superman, and she’s not Batman. To read the early Wonder Woman comics is to discover a cheerful team player, someone who doesn’t even really care if she ever gets credit no matter how many times Steve Trevor humbly credits her for feats men want to praise him for.

But to bring Wonder Woman to life on the big screen we have to confront the fatal flaws in her original origin story as an origin story for a superhero in the twenty-first century. There are three fatal flaws and one significant hurdle that we must overcome before we can see a Diana of Paradise Island (or Themiscyra, if you prefer) redirecting bullets with her silver bracelets.

First and most fatal is that William Marston’s gender essentialism is patently and incontrovertibly wrong. Marston’s vision of feminine virtue is in itself too sexist to withstand an American culture that has seen the publication of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique and at least put a few cracks into the glass ceiling. Marston’s vision of a matriarchal utopia was clearly developed before anyone saw the likes of controversial women in political power such as Margaret Thatcher or Indira Gandhi. The gender essentialism inherent in Marston’s creation will do nothing more than perpetuate a kind of class warfare between genders that runs counter to Marston’s long-term goals. Wonder Woman has to evolve beyond gender essentialism first before anything else. There are realizations of her that tackled this head-on but we can’t get to those just yet. Justice League comes a bit later.

The second fatal flaw in Wonder Woman’s original comic book origin stories is that Marston’s American exceptionalism is too explicit to permit any truly mythic development. Wonder Woman’s origin is tied too closely to World War 2 and Marston’s willingness to stump for the United States as the hope for equality of women everywhere. The trouble is that the 1940s America for which Wonder Woman goes to be a champion was a United States that still had racial segregation and a glass ceiling. Yet this was a United States that was given blessings by Marston’s drastically simplistic Greco-Roman pantheon which…

Third, gets us to the problems of Marston’s drastically simplistic Greco-Roman pantheon. However much Francis Schaeffer talked about the United States being a post-Christian culture, it’s not so post-Christian to embrace Wonder Woman’s explicitly pseudo neo-pagan origin. Or, rather, we know too much about actual Greco-Roman mythology to buy the purely gender delineated contrast between Mars and Aphrodite. Yet Aphrodite flip-flops in her decisions regarding the Amazons at just about any plot twist so that the ultimate goal of Diana leaving Paradise Island to help Steve Trevor fight Nazis can be reached.

That Wonder Woman was fashioned from a lump of clay and given life by a goddess gets us back to the problem of Marston’s gender essentialism for the goddesses more generally, but it’s worth noting again that in insisting on making Wonder Woman a golem with no father of any sort Marston was setting up a significant hurdle for Wonder Woman as a relatable character. Wonder Woman, as Steven Grant once said about Superman, is an embodiment of aspirations rather than passions, and the aspirational fantasy inherent in Wonder Woman has been tethered to a pseudo-pagan pantheon that is too easily offset by what we know from Greco-Roman literature. But there are seeds for rescue in this observation we can address down the road.

The fourth problem is just a big hurdle, which is that early Wonder Woman seemed cheerfully unconcerned with imposing her will on her adversaries through the use of her magic lasso (which was eventually de-powered down to just making people tell the truth, perhaps because everyone got the sense of just how totalitarian the original power of the magic lasso really was to begin with). Wonder Woman and Superman have both been written so as to be cheerfully free of the inner turmoil and conflict we associate with The Dark Knight.

A Wonder Woman who has no capacity to doubt whether she’s done the right thing (and whose sole stated weakness involves letting herself have her hands bound by her silver bracelets in a particular way by a man and not a woman) isn’t just a golem who could be a Mary Sue, she’s a character who can end up being the Law of Perfect Womanhood. She risks embodying the impossible standards of beauty for a particular cultural time and place. Nobody wants Wonder Woman to look like Etta Candy, for instance, but Wonder Woman would not be less who she is if she did happen to look the way Etta Candy often looked.

If we frame the story of a hero in terms of conflict then we may see quickly that Wonder Woman has no memorable foes in her rogues gallery compared to other superheroes. Superman has Lex Luthor, and Batman has the Joker, and these villains are compelling because they embody values antithetical to what the hero wants, but we don’t have a comparably compelling nemesis for Wonder Woman, do we? That isn’t because a rogues gallery is somehow a “male” thing. It’s not as though there wasn’t a “rogues gallery” in the film Mean Girls. Marston’s early gambit of having Wonder Woman’s enemies be Nazis or Nazi-sympathizers had been overplayed half a century later. To understand how to create a Wonder Woman nemesis that makes sense we don’t need to know what Wonder Woman is against but what she is actually for, and we need to find a thing that she is for that is worthy enough for a majority of Americans to consider worth fighting for. Whatever she fights for, Wonder Woman has to fight for it in a post-Cold War setting in which the moral certainties about American superiority inherent in Marston’s original set of origin tales can be jettisoned.

Wonder Woman’s roots in a Greco-Roman literary world might be a path to making her interesting. The Greeks gave us tragedy, and to appreciate tragedy we must remind ourselves that tragedy is not the triumph of evil over good. Tragedy is when the tragic figure chooses the lesser good over a greater good, or chooses the greater good at the loss of a lesser good, and finds that the two legitimate goods cannot possibly be reconciled. Wonder Woman has to be a truly anti-tragic heroic figure if she’s going to work within her pseudo-Hellenistic milieu. She needs to be able to thread the needle and find a way to balance largely irreconcilable aims. It’s in the nature of American pop culture to be anti-tragic and in favor of everything working out, maybe with a suitable group hug if possible. Wonder Woman can get there but she has to find a way to balance impulses that are often irreconcilable in reality in American culture, the impulse to individual self-realization and the impulse to group aspiration. Wonder Woman can make sense if she is the hero who fights the battle to balance contrasting and often conflicting honor codes that we attempt to live by. She can’t simply be a feminist icon because then all she will be is an icon and icons can get boring. The path of being a feminist icon will leave her a golem rather than a human of flesh and blood. Like many a figure in Greco-Roman literature she’s going to turn out to be more moral and scrupulous than the gods and goddesses angling for more worship around her. Wonder Woman has to be willing to do the right and honorable thing even if it brings dishonor to her or to others, but she has to also be willing to struggle to restore honor to groups. If she is going to be a superheroine for our era, she needs to be the opposite of American exceptionalism: she needs to start her superheroic adventures fighting on behalf of all humanity, not just Americans trying to defeat Nazis.

And there is at least one iteration of Wonder Woman that manages to thread the needle in a way that doesn’t require Wonder Woman to have her own rogues gallery and a flawless character. All of this has already been solved in a small screen format: the cartoon Justice League.

No more was Wonder Woman’s first adventure beyond Themiscyra (aka Paradise Island) a quest to help Steve Trevor and the United States fight Nazi Germany. Diana left the island in the 21st century to help humanity fight its apparently losing battle against a Martian invasion. She would get to meet Steve Trevor and be inspired by his bravery fighting Nazis soon enough, but the Justice League pilot showed her first fight to be for all of humanity–thereby solving the problem of American exceptionalism.

In a wonderfully ironic nod to Marston’s developing Wonder Woman as a reaction to what he considered Superman’s bloodcurdling machismo and to the cinematic nadir of the Christopher Reeve-era Superman, Diana joins the fight to save humanity from Martian invaders after they storm the earth, which has been left defenseless by Superman’s unilateral disarmament of the world’s nuclear arsenal. Diana’s first battle was to help save humanity from a threat that could only invade because of one (Super)man’s decision that he knew what was best for the rest of the planet. That seems like a decent tribute to Marston’s creating Wonder Woman to be a healthy alternative to what he considered unhealthy aspects about Superman’s form of masculinity.

By having Diana leave the island of the Amazons not to side with the United States but to fend off a literal Martian invasion she’s given an origin story that doesn’t tether her to any kind of American exceptionalism. It turns out that even the invading Martians aren’t native green Martians but parasitic white Martians but we’ll just get to that later.

The beauty of this narrative change made by the Justice League pilot was that it simultaneous addressed what we looked at as the third problem in Marston’s original origin, it’s simplified and implausibly idiosyncratic take on the Greco-Roman pantheon. The gods and goddesses are not necessarily good beings who have the best interest in humanity at heart. This is more or less directly addressed by Diana to her mother in the Justice League pilot. Seeing the white Martians invading and crushing human societies, Diana asks her mother why the Amazons don’t fight to protect mortals. Hippolyta’s answer is that there’s no obligation to protect mortals and that the gods will protect the Amazons.

Diana decides that she can’t accept an ethic in which mortals are allowed to be killed off and to presume upon the gods to preserve the safety of Earth. She’s already seen from the distance of her island home, that Darkseid’s armies invaded Earth from from Apokolips (from the end of Superman: the animated series). The Greco-Roman gods have remorselessly left mortals to galaxy-conquering gods before, and Diana is not interested in waiting to see whether or not the gods will sit by for this invasion, too. So the previously mentioned “problem three” has been solved, too. Diana is an immortal warrior who, though respecting the Greco-Roman gods, recognizes that they can be too feckless and self-serving to do the right thing by the mortals who have venerated them.

As for the fourth problem mentioned, i.e. Wonder Woman’s cheerful willingness to impose her will on others through her lasso, was remedied by a simple plot twist. Because Diana left Themiscyra to save mortals against Martian invaders without the consent of her mother, she took the weapons of her trade without having been trained in them and without having them “switched on.” She doesn’t discover the extent of what the lasso can do until she’s sent on a mission to deal with the business of gods and is told she had not been given access to her full range of powers because of how she left the island.

It also introduced a tension that runs throughout Diana’s storyline across Justice League/Justice League Unlimited—she did the right thing to fight to save humanity and the world, but by doing the right thing in the way she did she broke the taboos of her society and had to be banished. She did the honorable thing in a way that dishonored her culture’s norms and her mother’s wishes. So even though everyone recognizes she was a hero who made heroic sacrifices, by the laws of Themiscyra, Diana had to be punished as a lawbreaker, exiled for doing the right thing…a maid of honor in a dishonorable world. Because she left to fight the good fight without her mother’s knowledge or consent, Diana was not able to access the full scope of her powers and weapons to fight injustice until nearly the end of Justice League in its relaunch as Justice League Unlimited.

But the most difficult problem to solve was Marston’s gender essentialism. We now have decades of scientific studies that suggest that what Marston might have considered “innate” nurturing capacities in women and a willingness to submit could very easily be learned rather than organic traits of women (or men). People have to learn how to nurture. One of the playful threads in Justice League is that Diana grew up in a society that presumed a universal sisterhood, but once she leaves the island she discovers that, out in the world of mere mortals, that’s not how things work. When another princess jokes that the princess of the Amazons has feet of clay, Diana slyly replies, “You have no idea.” But the immortal super-powered golem begins to discover beyond the island of Themiscyra that the universal sisterhood she was taught existed doesn’t exactly hold out with mortals.

One of Diana’s battles in Season 1 of Justice League was against Erisia, a mortal woman adopted into the society of the Amazons who concludes from their teachings and society that men are the bane of the planet and must be eradicated. While Diana fights to stop this plot to massacre by magic plague, she protests that the misandry in Erisia’s crusade does not reflect the Amazon ethos. But Diana gets a needling from Hawkgirl that even if Erisia’s crusade doesn’t reflect the explicit precept of the Amazon, her misandry could be seen as a natural outworking of the no-males-allowed taboo of the Amazonian culture. It hardly seems a writerly accident that the uncouth “tomboy” of the League Hawkgirl is willing to tell Diana, woman to woman, that misandry might not be inherent in the Amazonian way but it sure would be easy to think it’s there.

It’s in Shayera Hol, Hawkgirl, one of the co-founding members of the Justice League that Diana finds not only an objection to the gender essentialism of Amazonian society, but also a regular annoyance. If Wonder Woman can be thought of as first-wave feminism, Hawkgirl can be thought of as perhaps second- or third-wave. Hawkgirl does not share Diana’s respect for or veneration of gods; she doesn’t believe in souls; she doesn’t believe the fates are benevolent; she doesn’t believe there’s a sisterhood; and she’d rather spend time with the men of the League than with Diana if she can help it. To Hawkgirl Diana is an elitist stuck-up princess who not only looks down on men in general but just about any woman who doesn’t agree with the way she thinks things should be done.

And as Diana fights against the forces of evil with the Justice League she begins to resent Hawkgirl, who she sees as an insolent thug without honor. When by the end of Season Two Shayera Hol turns out to be a spy and double agent for her home world Thanagar who sells out Earth, Diana is incensed. After all this time Hawkgirl has turned out to be a traitor. When Shayera helps the Justice League save the Earth from a Thanagarian war gambit that would destroy it, Diana just seems Shayera as a double traitor who exploited people and betrayed them. Diana’s loss of the illusion of universal sisterhood has come not from battles with supervillains but betrayal from the one other woman on the League.

Ironically, Diana doesn’t gain access to the full range of her powers in Justice League until the gods recruit her on a mission to rescue one of their own. Diana needs a weapon that can do harm to both gods and super-science and that weapon is Shayera Hol’s Nth metal mace. Shayera tells Diana that the weapon and her presence are a package deal. Diana has to serve the gods by being willing to forgive a traitor who has dishonored her and her allies. Ironically, Diana has to face the reality that this is the position she put her mother and the Amazonian society in when she left at the start of the series. The mission from the gods turns out to be a mission not only to save one of the gods, but a way to restore Diana back to her own people and mend her relationship with Hawkgirl.

So far from being a perfect embodiment of the Law of Ideal Womanhood, Justice League‘s Diana turns out to be relatably fallible. She’s given a more traditionally Greek story in which she chose the greater good of saving humanity at the expense of losing honor for herself and her people. What makes her an American hero is that she wins that honor back. With help from some time-traveling battles against an ageless supervillain Diana even gets to fight alongside Steve Trevor against Nazis. In other words, the full scope of Diana’s “origin story” ended up distributed across the entire run of the Justice League series in a way that solved the problems we’ve looked at while retaining the core narrative points of the origin series.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply