I’m that guy who made you watch “Lazy Sunday” two years after it aired on SNL, because he just heard it on his Weird Al Pandora station. (My gracious brother and sister-in-law have mercifully never mentioned it since.) Today, I’m the guy who heard a clip of Hamilton—after it smashed from Off-Broadway to Broadway to the Grammys—and has been obsessed ever since. Whatever, though, because I’m all in.

I’m that guy who made you watch “Lazy Sunday” two years after it aired on SNL, because he just heard it on his Weird Al Pandora station. (My gracious brother and sister-in-law have mercifully never mentioned it since.) Today, I’m the guy who heard a clip of Hamilton—after it smashed from Off-Broadway to Broadway to the Grammys—and has been obsessed ever since. Whatever, though, because I’m all in.

One of the odd features of Hamilton (a mostly hip-hop biography of Alexander Hamilton by Lin-Manuel Miranda) fandom is that most people cannot feasibly see the play anytime soon. It’s currently playing in one New York theatre, and there are no ancillary visual media widely available. I’m stuck waiting for the West Coast tour, starting sometime next year. I’m definitely not the only one who’s loving the play sight unseen–there are at least two podcasts on iTunes that are analyzing the soundtrack song by song.

Besides the indescribably good soundtrack, we have two clips, both of the opening song, “Alexander Hamilton.” The song details the events in Hamilton’s life through age 19, when he joined the revolutionary army. The first clip was filmed in 2009, six years before Hamilton‘s Broadway opening. The other clip is the full-cast performance from the Grammys last month. This may not seem like much, but the clips give the world insight into the creative process that produced a musical about “the ten-dollar founding father without a father.”

Clip 1, available on the White House YouTube channel, is a solo performance by Lin-Manuel Miranda, the play’s writer and original-cast star. Miranda is dressed in a black-tie tux, and his audience is President and First Lady Obama plus assorted guests. This was the first performance of any work from Hamilton, which started when Miranda began reading a popular biography and wondered (of course!) why no one had given this story a hip-hop twist. Miranda admits to the audience that it sounds ridiculous and interrupts the light chuckles with, “You laugh, you laugh!” He proceeds to state his case: Hamilton was born illegitimately in the Caribbean and wrote his way out of poverty, a path analogous to the biographies of many successful hip-hop artists. A bit embarrassed, he explains that the song is from the perspective of Aaron Burr and invites everyone to snap along. His audience is won over from the first lines onward:

How does a bastard, orphan, son of a whore and a

Scotsman,

dropped in the middle of a

Forgotten spot in the Caribbean

by providence

impoverished, in squalor

grow up to be a hero and a scholar?…The world is gonna know your name. What’s your name, man?

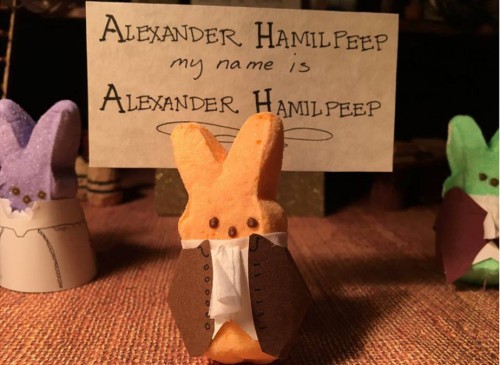

Alexander Hamilton

My name is Alexander Hamilton

And there’s a million things I haven’t done

But just you wait, just you wait…

His tone here is at once confident, excited, and embarrassed. He seems absolutely passionate about Hamilton as a hip-hop hero, ecstatic that he gets to give the idea to such an important audience, and scared that it won’t go over as well as he imagined. It almost doesn’t–he says the first “Alexander Hamilton” awkwardly, almost ironically. The rest of the song, though, is the opposite of ironic. It’s bold, sincere, celebratory; it’s “Who am I? Two-four-six-oh-one!” not, “Hello, my name is Elder Cunningham!” Compare that first “Alexander Hamilton” as well as the tentative ending with Miranda rapping this rapid-fire section:

There would have been nothin’ left to do

For someone less astute

He woulda been dead or destitute

Without a cent of restitution

Started workin’, clerkin’ for his late mother’s landlord

Tradin’ sugar cane and rum and all the things he can’t afford

Scammin’ for every book he can get his hands on

Plannin’ for the future see him now as he stands on

The bow of a ship headed for a new land

In New York you can be a new man

This verse is much closer to the tone of the full-cast performance from the Grammys last month (sorry folks, couldn’t figure out how to embed!). The song starts and ends with Burr, who is the main narrator through the rest of the play; this final draft of the song, though, includes all the major characters: his wife Eliza, Washington, Jefferson, Madison, John Laurens. The full-cast performance much better conveys the line, “America sings for you!” Moreover, Manuel emerges dramatically a minute in, and there is no awkwardness–only bravado–when he answers Burr’s question, “What’s your name, man?”

This is not to say that Miranda’s White House performance was deficient. He brought the house down, and the annotations on Genius.com suggest the song was a recent creation when it was first performed. The song was originally conceived as track one of a concept album, which explains the self-deprecating tone of some of his original performance. It took him years afterward to find the truest, best medium for the subject matter. Miranda explains,

And then everyone goes, ‘Oh, my God, he’s a genius! Hamilton’s a genius!’ They conflate the two. I’m not a…genius. I work my ass off. Hamilton could have written what I wrote in about three weeks. That’s genius. It took me a very long time to wrestle this onto the stage, to even be able to understand the worldviews of the characters that inhabit my show, and then be able to distill.

The lesson of Hamilton for creators is not to pilfer history and wrench our forefathers (and mothers) into the present. Hamilton works because its final tone and presentation match the man being celebrated. Miranda’s creative process was not primarily driven by strict historical accuracy. Rather, he found a way to sing along with Hamilton across the centuries, and now millions more are singing along.

More specifically, you can see and hear the development of Miranda’s production from the White House performance to the full-cast version. Importantly, Hamilton is not totally faithful to the biography by Ron Chernow on which it is based. The conversation between Burr and Hamilton about first enrolling into Princeton and then joining the revolution (“Aaron Burr, Sir” and “My Shot”) seems to be fiction (I’m about 50 pages into the book, though). The brilliant and raucous “My Shot” likewise seems to place Hamilton’s revolutionary leanings much earlier in his youth than the actual chronology of events. Much of Miranda’s work, then, was spent in developing Hamilton as the star of a show grand and spectacular enough to match the spirit, though not the letter, of its subject. And it works so well. I challenge you to listen to the Revolutionary War sequence and honestly say you don’t get goosebumps (“Right Hand Man” through “Yorktown (The World Turned Upside Down,” particularly the latter).

When I started to adopt writing as a vocation, I benefitted greatly from Stephen King’s On Writing–especially the first to final draft of “1408.” I imagine that including a Lamottian “shitty first draft” required some courage. Miranda showed similar courage when he put his new, brilliant, incomplete “Alexander Hamilton” on display for President and Mrs. Obama. Analogously, we can consider ourselves rough drafts that God will make whole on His own power, in His own time.

Hamilton suggests that we, ultimately, have little control over ourselves and the world around us: George Washington tells Hamilton, “You cannot control who lives, who dies, who tells your story.” All of Hamilton’s efforts to prove himself to his revolutionary brothers, high society, the nascent government’s leaders, and history itself could not stop the decades of neglectful treatment of his legacy. But Eliza–his undeserved, faithful wife, who stayed even after his very public affair was made known–ends the song and the play, telling us she lived another 50 years. She recovered his legacy, collected his works, continued his political efforts, and founded an orphanage as tribute to her “bastard, immigrant, son of a whore and a Scotsman” husband. Eliza steps in and saves her beloved Hamilton from fading away from the American story, not unlike Jesus who forgives us and redeems the parts of us that we could never redeem on our own.

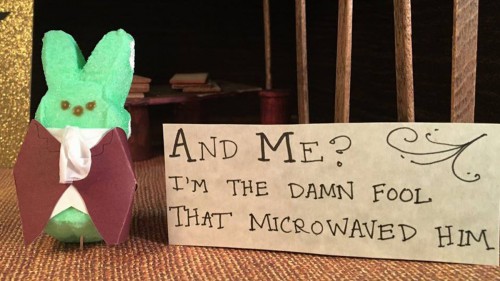

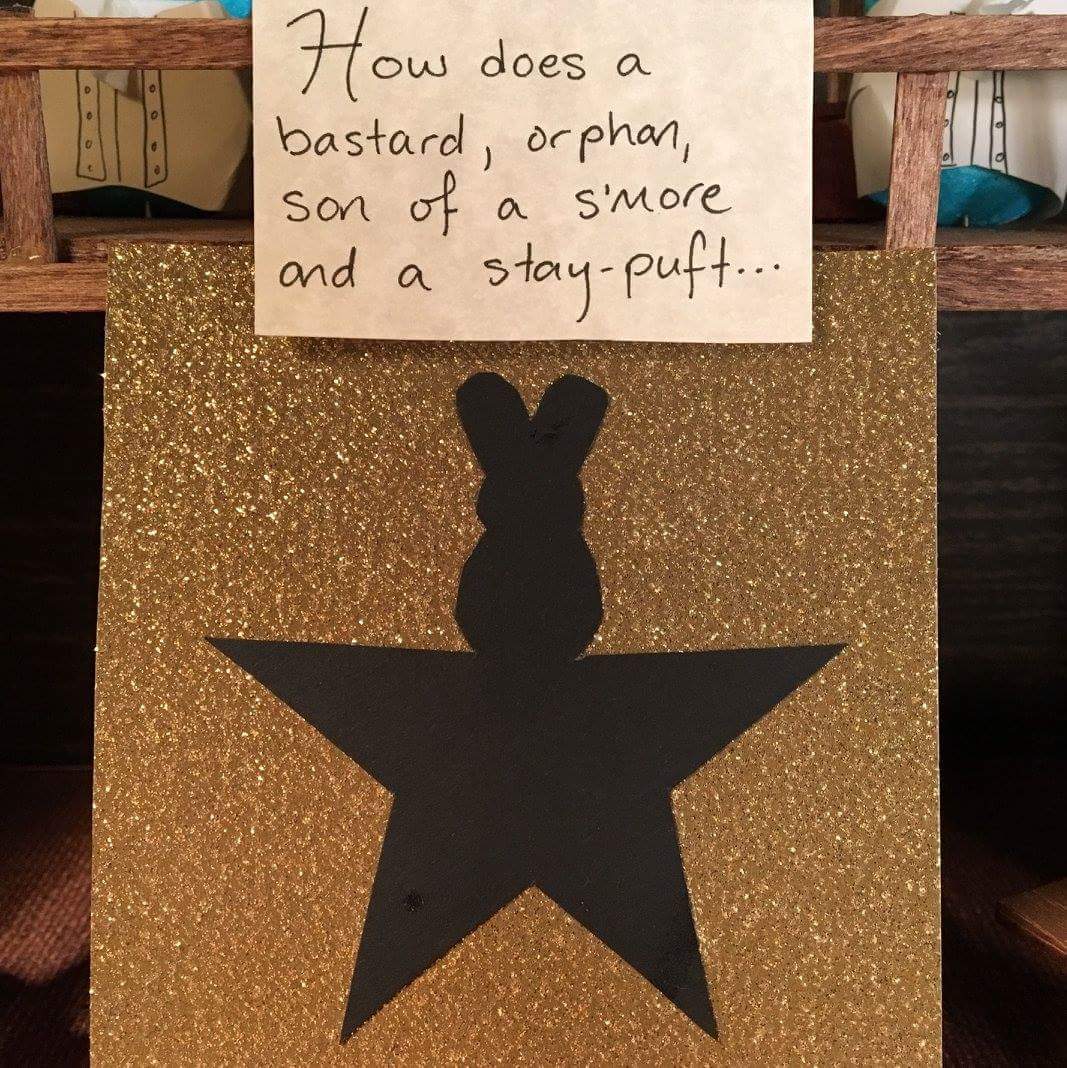

Alexander Hamilpeep and friends are copyright Kate Ramsayer, from her brilliant diorama.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply