This lovely reflection on rejection, resurrection, and Vincent Van Gogh comes to us from our friend Elsa Wilson.

Anchorage, Alaska isn’t a fine arts hub by any stretch of the imagination. Most winter outings here mean skiing, hiking in crampons, or participating in the annual “Polar Plunge.” But every once and a while, the Anchorage Museum tempts Alaskans inside for a deeper perspective on our wild and rugged selves.

Anchorage, Alaska isn’t a fine arts hub by any stretch of the imagination. Most winter outings here mean skiing, hiking in crampons, or participating in the annual “Polar Plunge.” But every once and a while, the Anchorage Museum tempts Alaskans inside for a deeper perspective on our wild and rugged selves.

October 9th – Jan 10th, the Anchorage Museum offered an exhibit called Van Gogh Alive – the Experience. No physical art pieces were shown. Digital copies of paintings, drawings, letters, journal excerpts, and photos were projected onto entire rooms (sometimes including floors). Quotes mingled to correlate with the images projected, or maybe simply to augment the chaotic wonder of it all.

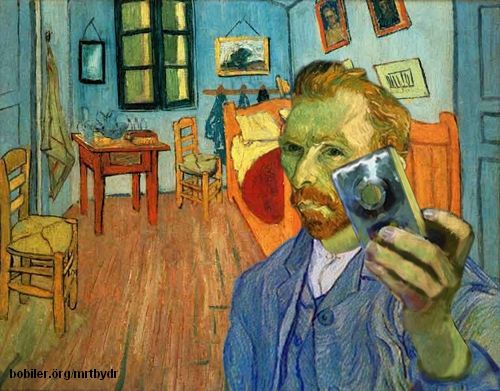

As I approached the first room of the exhibit, I wondered how they could make Van Gogh more “alive” than he already is. He is perhaps the most alive of any painter I know. The Olive Trees pulse at the edges of their frame every time I see them at the MoMA, New York City. But as I watched the exhibit’s narrative unfold – an arrangement currently on tour in Warsaw – I realized that it wasn’t only the art that was resurrected there. The experience seemed to exist as a reminder that we, too, could be resurrected. As I wandered between the projected light beams and the wall, the paintings were literally placed onto me, turning myself and other unsuspecting participants into image-bearers in a vaguely biblical sense.

These silhouettes – presences Van Gogh probably never predicted, but certainly painted for – took on all the walking shadowy shapes of kids who could barely toddle, little girls in tutus, grey-haired couples, bearded hunters in Carhartts, and tourists distinguished by unbelievably clean shoes.

“I have walked this earth for 30 years,” reads the artist’s own handwriting transposed onto the wall, “and, out of gratitude, want to leave some souvenir. Taking the “souvenirs” is a little like dipping your hand into a pool of water to take a sip – a little water stays on your hand and a little drips down to form a ripple that wasn’t there before. It goes beyond just a life, to a life more abundantly.

“I have walked this earth for 30 years,” reads the artist’s own handwriting transposed onto the wall, “and, out of gratitude, want to leave some souvenir. Taking the “souvenirs” is a little like dipping your hand into a pool of water to take a sip – a little water stays on your hand and a little drips down to form a ripple that wasn’t there before. It goes beyond just a life, to a life more abundantly.

The exhibition relied on a striking context: an audience that would anticipate the work being shown. Throughout the two-room display, a carefully curated NatGeo-like “B-roll” played to correspond to the paintings – footage of cypress trees and cherry blossoms – as if to help us see what Van Gogh saw before he painted it. But of course we can never truly see what he saw, that was his genius. In the exhibit, we were not so much seeing what he saw, but rather we were realizing how much he has shown us. We knew what was coming next. Real-life waving wheat fields stretched a room’s length; and I knew The Sower would stride toward me through twenty-foot-high rows of earth. When we hushed to hear the chirping of crickets and the room dimmed to hold satellite space photos, I knew the more magical Starry Night would soon swirl around me.

This reliance on the audience connecting the dots felt ironic since Van Gogh struggled with people not recognizing his talent. “I can’t change the fact that my paintings don’t sell,” I read next to a painting that most people in the room probably owned in coffee-mug form, “But the time will come when people will recognize that they are worth more than the value of the paints used in the picture.”

“The time” has indeed come – this entire touring exhibition depends on the audience’s familiarity with Van Gogh’s work, and the assumption that we will keep finding enticement anew.

“I am seeking, I am striving, I am in it with all my heart.” That “it” is what people keep coming back to: that wild juxtaposition of beauty and violence, paired with the self-awareness of an artist who plunged into it all.

My initial concern was that the exhibit intended to make my favorite artist more vivid than he was with no curator’s help. I discovered that the exhibit didn’t attempt to “package” the art’s value, but offered a space to kindle a relationship. It was a place for a mismatched crew to experience the chronological resurrection of art that rose from the ashes of rejection. As the art spoke and we listened, it became a place to find little personal resurrections from whatever mundane, lonely, chaotic winter day we had stepped out of. Most heads in the dark room nodded in sync at the quote, “I wish they would only take me as I am.” It seemed this mad man had caught us all wanting the same thing. In a fever of depression and determination, Van Gogh once said, “A great fire burns within me, but no one stops to warm themselves.” In the end, the exhibition was a few rooms in a slushy city where we could stop to warm ourselves. Maybe it wasn’t so much about Van Gogh’s art being alive, but about us being alive.

I found the “great fire” still alive, but not of it’s own ignition. The downfall of humanism is that the “fire within” is only within. When humanity is the sole source of anything, it usually ends badly. But when the fire within reflects its source without, grace is surely at play. In the exhibit, my body reflected the projected images of the artist. At risk of being heretical, I’ll say it felt like an anointing – a faint (and certainly little “p”) pentecost in a world teeming with grace. As I looked around the room at the other gallery-goers, I saw rich images breaking and bending their light beams as they hit all of us. Just as Van Gogh asked to be “taken as I am,” the images took us as we were, and transformed us. And it wasn’t the first time rejection resulted in resurrection.

To borrow a phrase from Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, we “carried the fire” not because it was ours to carry but because it filled us, and surrounded us. At that point – like the big “P” Pentecost – the light on the outside began to reflect what was happening on the inside. It wasn’t our accomplishments that sustained us in that room, but someone else’s. And there – wrapped in thick strokes of oil-painted heavens – I suddenly remembered: that’s how grace works.

To borrow a phrase from Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, we “carried the fire” not because it was ours to carry but because it filled us, and surrounded us. At that point – like the big “P” Pentecost – the light on the outside began to reflect what was happening on the inside. It wasn’t our accomplishments that sustained us in that room, but someone else’s. And there – wrapped in thick strokes of oil-painted heavens – I suddenly remembered: that’s how grace works.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply