Welcome to the fifth installment of author Ted Scofield‘s series on everybody else’s biggest problem. If you missed one or more of the previous installments, you can find them here. New installments will be posted every two weeks, on Tuesdays.

Before you dive headlong into this latest installment on everybody else’s biggest problem, please take a moment to answer one quick question: Considering your current annual income, how much more money do you need to feel comfortable?

We’re examining nine common responses to the question, What is greed? Think of them as nine attributes of the concept or, perhaps more fittingly, nine symptoms of the affliction. In Part 3 we looked at the most commonly cited greed symptom, abundance, and concluded “too much stuff” is impossible to quantify. Last time we examined utility – how you use your money – and reached the same conclusion. Today we’ll delve into a third piece of the greed puzzle by asking ourselves, Are we greedy if we’re not satisfied with what we have?

Let’s start by returning to the opening question: How much more money do you want or need to feel comfortable? How much more will make an appreciable difference in your life?

Remarkably, studies show that most people, regardless of income, answer the question the same way: We need about 10% more to feel comfortable. Ten percent will make a difference, and whether we earn $30,000 per year or $60,000 or $250,000 or a cool million, just 10% more is what we want.

When people are asked the same question over time, Loyola Marymount University Professor Christopher Kaczor reports “when they do get that 10%, which typically happens over the course of a few years, they want just another 10%, and so on, ad infinitum.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jadvt7CbH1o

How can this be? Why are we never satisfied with what we have?

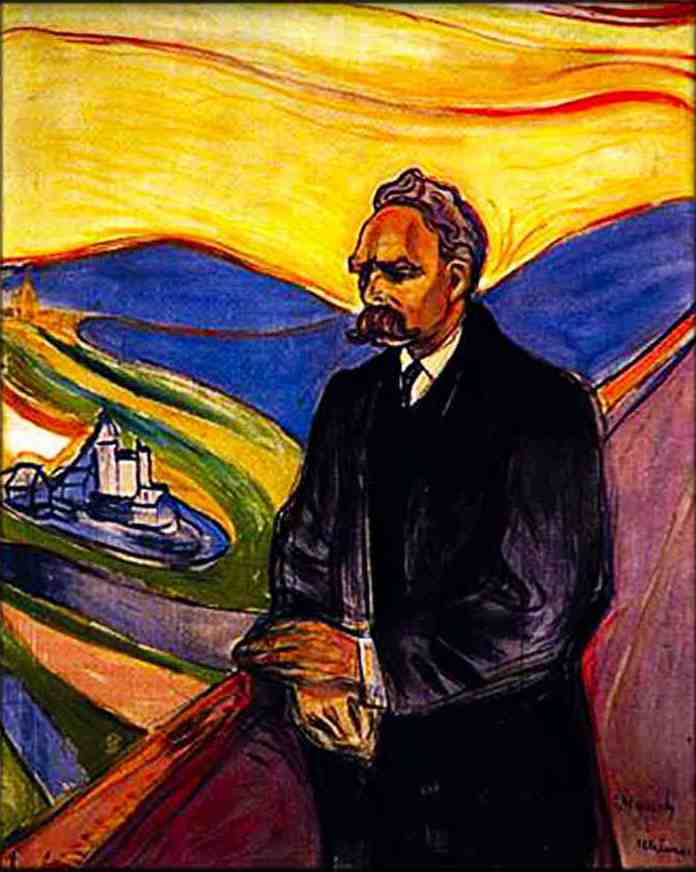

Friedrich Nietzsche hints at a possible answer:

Even the most beautiful scenery is no longer assured of our love after we have lived in it for three months, and some distant coast attracts our avarice: possessions are generally diminished by possession.

In 21st century terms, here’s what the little preacher is saying: “I sure do love my new Jeep Patriot! … That BMW X5 looks really nice … You know, what I really want is a Porsche Cayenne Turbo … Did I hear that Bentley is making an SUV? … That’ll surely satisfy me!”

Is Nietzsche right? Do we want just 10% more because we grow accustomed to what we possess and quickly desire something shiny and new? Is there no limit to, or end to, our desire for more?

Psychiatrist Neel Burton argues that today the object of desire is no longer satisfaction, but desire itself. Dr. Burton faults our culture for our inability to feel satisfaction:

It so happens that our culture – or lack of it, for our culture is in a state of flux and crisis – places a high value on materialism and, by extension, greed. Our culture’s emphasis on greed is such that people have become immune to satisfaction.

British psychoanalyst Joan Riviere takes it a depressing step further and folds our unquenchable desire into our double helix, concluding that “by its very nature [greed] is endless and never assuaged; and by being a form of the impulse to live, it ceases only with death.”

Does our culture force us into a permanent state of dissatisfaction or, worse yet, are we hardwired to always hunger for more?

Does our culture force us into a permanent state of dissatisfaction or, worse yet, are we hardwired to always hunger for more?

I’ll leave that fascinating question to the sociologists and anthropologists and steer us back on the path of our original quest, a collectively applicable definition of greed and the role satisfaction plays therein.

Erich Fromm famously said: “Greed is a bottomless pit which exhausts the person in an endless effort to satisfy the need without ever reaching satisfaction.”

And I suggest that most if not all of us agree that at some point, if a person – not you and me of course – cannot be satisfied with his money and possessions, that person is indeed greedy.

A couple of weeks ago, for example, Steven Spielberg took some heat in the press when it was reported that he wasn’t satisfied with The Seven Seas, his $184 million, 252-foot yacht, so he’s “upgrading” to a $250 million, 300-foot yacht instead. He was labeled “greedy.”

When your brother-in-law buys a new convertible, with the optional smirk of course, or your sister visits with a new Birkin, perhaps you’ve been tempted to apply the same label: Greedy!

But where on the vast multi-axis spectrum of money, desire, stuff and satisfaction do we cross the line from “Who, me?” to “J’accuse!”? A mega-yacht. An exotic car. A coveted handbag. A second pair of shoes. A roof overhead. Food on the table. Can we as members of our common culture (and species) agree on when a person should be “satisfied”?

Seneca said “It is not the man who has little, but he who desires more, that is poor.” I’d guess that no one reading this post right now is genuinely poor. I doubt you want for food or clothing or shelter. I doubt you want for HBO. I certainly do not. But I also guess we all desire more. I admit I’m in that camp and, frankly, I don’t think 10% will do it for me.

Why?

May I please blame our shallow, materialistic culture or, better yet, my highly-evolved DNA? It’s not my fault I’d like another bedroom, and definitely another bathroom, and, yes, a second home where the cool kids spend their summer weekends. Might I alibi my lack of satisfaction with a wild tale of a cultural boogeyman or a scientific wizard of want?

Professor Kaczor pulls back the curtain on my folly:

At all levels of wealth, from modest to tremendously wealthy, people tend to compare themselves to those who are just ahead of them in riches. Parents making $40,000 a year tend not to say, “Wow, we are doing so much better than 95% of the entire world. We have one TV and one car. We have a computer. We’re doing amazingly well financially.” Rather, they tend to look at those with two cars and three TVs, who in turn compare themselves to those with newer cars, bigger houses, and plasma-screen TVs, and so on.

To put it in terms that a modern-day Nietzsche might appreciate, that Jeep Patriot in your garage is a dream come true until your neighbor pulls into her driveway in a gleaming X5. We don’t compare ourselves to the disabled veteran sleeping in the alley, grateful for what we have. No, we compare ourselves to our siblings, our classmates, our co-workers, “the Joneses,” our peers. And we are not satisfied until we have as much or more than they do and, as long as someone has more than we do, we are not greedy. Greed remains somebody else’s problem.

It stings my soul to write those words. But it’s true, isn’t it? Few of us need or would even want to upgrade our yacht or home or car absent others having done so. Our satisfaction is relative to what others possess, not what we need to possess or even think we want to possess. And because our satisfaction is indeed relative to the Joneses, we will never collectively agree as a culture or a species when we should be satisfied. Unconsciously we pencil a line around our own little ecosystem, our personal cul-de-sacs on which we unceasingly compare ourselves to our self-defined neighbors, and within we all want a “bigger boat” until there are no bigger boats to be had.

Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain. You’ll only reveal yourself.

Next time we’ll swim in these existentially dangerous waters and see if we can define greed in terms of relatively, a fourth commonly cited symptom of the greed affliction.

COMMENTS

3 responses to “Everybody Else’s Biggest Problem, Pt. 5: You’re Gonna Need A Bigger Boat”

Leave a Reply

Wow. This one really hits home and is my favorite one of the bunch so far. I’m a guy who likes a new car every two years so I’ve been leasing for 8. Each new car has been an “upgrade” and absolutely I compare myself to both my brother and my close friends. Yes I want to show I’m doing well at my job by having nicer things than they do. Is that wrong? Does it make me greedy? I’d say No about myself but I’m sure I’d say Yes about another person and the same set of facts. Greed does defy any easy definition. We all know it when we see it — in other people.

I struggle with comparing myself to other people. I don’t want to, but it’s really hard in our culture not to want what other people have. My Christian faith tells me not to idolize money and possessions, but my ambition needs a way to keep score. How do we balance the two?