Alfred Hitchcock agreed to sit down with François Truffaut for a five-day interview in August 1962. The Frenchman aimed to pick the master’s brain and snag some good tidbits for interested cinephiles. Gradually, their conversation started to flow and the product was a wonderful book. In its introduction, Truffaut calls Hitchcock an “artist of anxiety.” While he is pointing at his knack for touching on our “nighttime, metaphysical anxieties,” I found the examples of Hitchcock’s own daily worries very interesting.

Here’s Hitchcock on his anxious desire to keep everything running according to plan:

I’m full of fears and I do my best to avoid difficulties and any kind of complications. I like everything around me to be clear as crystal and completely calm. I don’t want clouds overhead. I get a feeling of inner peace from a well-organized desk. When I take a bath, I put everything neatly back in place. You wouldn’t even know I’d been in the bathroom. My passion for orderliness goes hand in hand with a strong revulsion toward complications.

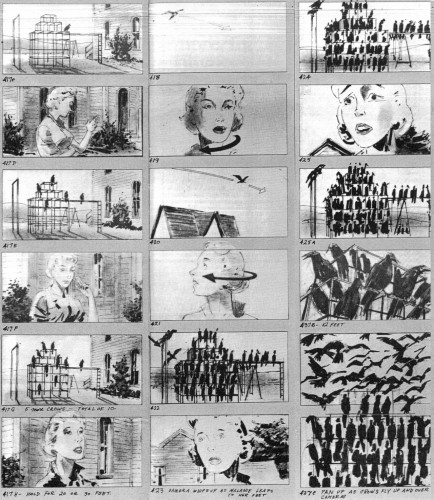

Considering that his 54 films are all products of careful, shot-by-shot storyboarding and meticulous editing, this level of OCD in daily tasks isn’t very surprising. A skilled filmmaker requires this level of control on set. Hitchcock’s anxieties toward taking a bath and organizing his desk are extensions of the quirks that made him such a prolific artist.

His perfectionism and need for final cut also turned into anxieties that he voiced with Truffaut:

The story department here sends me all kinds of properties which they claim are likely to make a good Hitchcock picture. Naturally, when I read them, they don’t measure up to Hitchcock standards. How lucky you are not to be categorized and stamped as I am, for this is the root of my difficulties in acquiring a good subject, especially in respect to acceptance by the audience.

Hitchcock always deferred to the audience, and he sought to never waste a shot on something dull or peripheral. “Some films are slices of life, mine are slices of cake,” he said. Yet, just like his fear of complications in the first quote, his perfectionism here had the potential to be crippling. What’s lovely about Hitchcock and what allowed him to make so many great movies is the cool head he keeps despite this obsession with control and perfection.

Here he seems to capture the perfect artist’s sensibility:

The desire to do something big and, when that’s successful to go on to something else even bigger is like the little boy who’s blowing up a balloon and all of a sudden it goes Boom! right in his face. I never reason that way. I might say to myself, “Psycho will be a nice little picture to do.” I never think, “I’m going to shoot a picture that will bring in fifteen million dollars”: that idea never enters into my mind.

It’s ironic and even quite beautiful that a man so fastidious in his daily routines and professional life specialized in shaping characters who had lost all control. Hitchcock’s favorite storyline revolves around an innocent man who is wrongly accused and forced to take action to clear his name or save his skin.

Take the iconic cornfields scene in North By Northwest. In the film, Cary Grant plays an innocent ad executive who is mistaken for somebody else and is being chased down by a ruthless spy and his cronies. Hitchcock’s approach to this specific scene shows his desire to play on the deepest anxieties of his audience – that nowhere is safe and nothing should be taken for granted:

I found I was faced with the old cliché situation: the man who is put on the spot, probably to be shot. Now, how is this usually done? A dark night at a narrow intersection of the city. The waiting victim standing in a pool of light under the street lamp. The cobbles are “washed with the recent rains.” A close-up of a black cat slinking along against the wall of a house. A shot of a window, with a furtive face pulling back the curtain to look out. The slow approach of a black limousine, et cetera, et cetera. Now, what was the antithesis of a scene like this? No darkness, no pool of light, no mysterious figures in windows. Just nothing. Just bright sunshine and a blank, open countryside with barely a house or tree in which any lurking menaces could hide.

The scene opens to a landscape with no foreseeable threat. I sit back, go for an extra big handful of popcorn, exhale for a second. Then, “That’s funny, that plane’s dustin’ crops where there ain’t no crops,” a bystander tells Grant. Boom. Back in the hot seat. Even when we think we are the very safest in our own skins, fully in control, Hitchcock suggests, we are completely exposed.

COMMENTS

One response to “Alfred Hitchcock: Artist of Anxiety”

Leave a Reply

Good stuff, Dave! Love Hitchcock. I believe that in the same interview (maybe a different one) AH talks about how he favors suspense over mystery, stating that mystery is more or less the the element of surprise. The audience gets 30 seconds of BANG with mystery. On the other hand, suspense lets the audience know the character is in trouble. This way the audience gets a greater longevity of tension, knowing something that the character does not, yet still not knowing how things will end. I find this to be an interesting pairing with his perfectionism/desire for control. Even though puts his characters in out of control situations, he always gave the viewer a tiny grip of control, almost like giving a drug addict a small hit just to ease the withdraw.