1) Kicking off this week’s roundup we have a story that posted last week over at Modern Love. Entitled, “To Fall in Love with Anyone, Do This,” it posits the theory that intimate love can happen between any two people willing to open themselves up. We read to find that not only has this theory been tested, by a scientific researcher named Dr. Arthur Aron, but that it is also put to the test by the writer herself, on a first date, in a bar. And it works.

It sounds like another sensationalized love algorithm, but the thought behind it makes a lot of sense in comparison to how we generally conceive of how love “happens”. More than the myth of fates and stars, it starts with something akin to two deaths.

The writer and her prospective love-mate agree to ask each of the 36 questions in the bar, passing the iPhone back and forth between each other, the idea being, as our man Daniel Jones describes, “Allowing oneself to be vulnerable with another person can be exceedingly difficult, so this exercise forces the issue.” Then you’re supposed to stare at one another for 4 minutes.

I know the eyes are the windows to the soul or whatever, but the real crux of the moment was not just that I was really seeing someone, but that I was seeing someone really seeing me. Once I embraced the terror of this realization and gave it time to subside, I arrived somewhere unexpected.

I felt brave, and in a state of wonder. Part of that wonder was at my own vulnerability and part was the weird kind of wonder you get from saying a word over and over until it loses its meaning and becomes what it actually is: an assemblage of sounds.

… I wondered what would come of our interaction. If nothing else, I thought it would make a good story. But I see now that the story isn’t about us; it’s about what it means to bother to know someone, which is really a story about what it means to be known.

It’s true you can’t choose who loves you, although I’ve spent years hoping otherwise, and you can’t create romantic feelings based on convenience alone. Science tells us biology matters; our pheromones and hormones do a lot of work behind the scenes.

But despite all this, I’ve begun to think love is a more pliable thing than we make it out to be. Arthur Aron’s study taught me that it’s possible — simple, even — to generate trust and intimacy, the feelings love needs to thrive.

The essay ends with, “Love didn’t happen to us. We’re in love because we each made the choice to be.” Now this, to me, sounds a lot less like human agency and lot more like the power of vulnerability, and the closeness feeling loved has with feeling known. As a This American Life episode once put it, this way of viewing love is something akin to “a mutual death contract,” an agreement to pass on the romanticism of a love spark, and to take up the cross of your own known-ness.

2) And speaking of “knowing,” it seems this has been a theme in the last couple weeks. How do we process information these days, and how do we do it differently than we used to, if it is different at all? Based on several reports, the lead-off article on last week’s Weekender included, how we “know” these days is measured, in most part, by the power of our ever-refreshing internal hard-drives—the kinds of media we consume, the amount we consume, and the interfaces through which we consume them. The Atlantic posted this week the “Cathedral of Computation,” a piece that drives parallel to DZ’s amazing “ICYMI” piece Wednesday. The essay argues that our Enlightenment division of God and Science has become inverted, which creates all sorts of interesting ways we begin to see ourselves as people of progress (ht BFG).

2) And speaking of “knowing,” it seems this has been a theme in the last couple weeks. How do we process information these days, and how do we do it differently than we used to, if it is different at all? Based on several reports, the lead-off article on last week’s Weekender included, how we “know” these days is measured, in most part, by the power of our ever-refreshing internal hard-drives—the kinds of media we consume, the amount we consume, and the interfaces through which we consume them. The Atlantic posted this week the “Cathedral of Computation,” a piece that drives parallel to DZ’s amazing “ICYMI” piece Wednesday. The essay argues that our Enlightenment division of God and Science has become inverted, which creates all sorts of interesting ways we begin to see ourselves as people of progress (ht BFG).

Here’s an exercise: The next time you see someone talking about algorithms, replace the term with “God” and ask yourself if the sense changes any. Our supposedly algorithmic culture is not a material phenomenon so much as a devotional one, a supplication made to the computers we have allowed to replace gods in our minds, even as we simultaneously claim that science has made us impervious to religion…

The worship of the algorithm is hardly the only example of the theological reversal of the Enlightenment—for another sign, just look at the surfeit of nonfiction books promising insights into “The Science of…” anything, from laughter to marijuana. But algorithms hold a special station in the new technological temple because computers have become our favorite idols.

… Each generation, we reset a belief that we’ve reached the end of this chain of metaphors, even though history always proves us wrong precisely because there’s always another technology or trend offering a fresh metaphor. Indeed, an exceptionalism that favors the present is one of the ways that science has become theology.

Not only do these trending pop-science mediums lend us the comfort of “understanding” elements of who we are and how we work, but they become the way in which we safeguard and differentiate ourselves from our dead forebears.

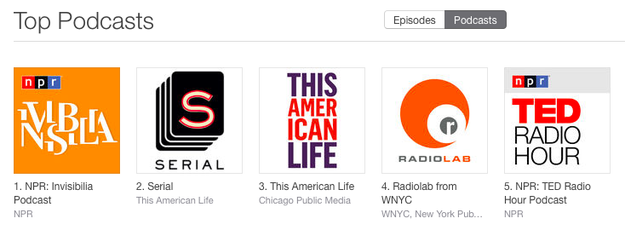

Anyways, enough of that dystopian nonsense! Just because we found a new set of fig-leaves doesn’t mean it can’t be fun. Why not indulge ourselves with a new incarnation of this trend? If you’ve been missing Serial—I know I have!—next in the hopper for Podcast initiates is Invisibilia, whose first two (really good) episodes are out now, and boasts the coolest of theo-scientific mission statements:

Launching in January 2015, Invisibilia (Latin for “all the invisible things”) explores the intangible forces that shape human behavior – things like ideas, beliefs, assumptions and emotions. Co-hosted by NPR’s Lulu Miller and Alix Spiegel, who helped create Radiolab and This American Life, Invisibilia delves into a wide array of human behavior, interweaving narrative storytelling with fascinating new psychological and brain science. Listen and research will come to life in a way that will make you see your own life differently.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vuVAP_4TQEY&w=600]

3) For the theology lovers out there, there’s a great piece on the concept of “moral progress” as it relates to Christianity, written by Fr. Stephen Freeman. Based on the story of St. Mary of Egypt, the article discusses how the stories of the early church fathers and mothers depict moments of great moral reform, where the believer is radically moved into a higher way of being. This picture, argues Freeman, is a modern thought, and a modern mistranslation. Moral progress is not written into the semantics of sainthood. Rather, the word to use is “repentance,” which finds transformation with self-emptying, not self-improvement. Freeman uses the Recovery Movement as a clear picture of this transformation (ht AZ).

It is, of course, possible to describe the changes that occur in the state of repentance as “progress,” but this distorts the work that is taking place. In the words of the Elder Sophrony, “The way down is the way up.” The self-emptying of repentance is not the work of gradual improvement, a work of “getting better and better.” It is a work of becoming “lesser and lesser.” We are not saved by moral progress, transformed by our efforts. It is not self-improvement.

Because of the metaphors and images that dominate our culture, we quickly assume that change (for the good) is an improvement. But included within the progressive metaphor is an assumption of stability and a self-contained quality of goodness (improvement). Thus, if I buy a piece of property and make “improvements,” it is no longer the same. The streets and sewers that have been installed are now part of the property. In human terms, we presume that “progress” gained in the battle with the passions results in an improved self, a self that is less a prisoner to those same passions.

The human life is a dynamic relationship. We are not streets and sewers and electrical gridwork. What is “acquired” by grace in the work of repentance is a different dynamic, one in which our life is centered in the life of God. Repentance is never a one-time event – it is a mode of existence.

4) This week, Yahoo! Exec Marissa Mayer described a different mode of existence in the workplace—not at Yahoo, but at Google, her old office. Google, of course, is long-renowned for their work environment, among the perks is their “20% time” policy each week, which allows employees free time to invent, tinker, dream up any personal project they may have in mind. Imagine, a whole workday each week, to do that hobby project you’ve never had time to entertain.

Mayer says the policy doesn’t actually exist. Rather than taking Tuesdays off to build that glow-in-the-dark dartboard, the policy is just another fine-print trapdoor for modern performancism. It’s not that you should take time off to find inspiration, it’s that you should do all your work—and exceed that work with inspired work (ht BJ).

“I’ve got to tell you the dirty little secret of Google’s 20% time. It’s really 120% time.”

She said that 20% time projects aren’t projects you can do instead of doing your regular job for a whole day every week. It’s “stuff that you’ve got to do beyond your regular job.”

5) Capping it off on a heavier note, but a beautiful note, nonetheless, the New York Times Couch series is proving just another outlet for good human interest stories. This story, released last Saturday by Patrick O’Malley, tells of a mother grieving over the loss of her newborn daughter. As her grief continued for months, the mother—normally a self-sufficient, self-contained individual—began to feel concern that she wasn’t grieving “right,” that if she had grieved “better,” she would be finished by now. What her doctor describes is a performance anxiety in a place where performance or best practices is not applicable.

Very gently, using simple, nonclinical words, I suggested to Mary that there was nothing wrong with her. She was not depressed or stuck or wrong. She was just very sad, consumed by sorrow, but not because she was grieving incorrectly. The depth of her sadness was simply a measure of the love she had for her daughter.

A transformation occurred when she heard this. She continued to weep but the muscles in her face relaxed. I watched as months of pent-up emotions were released. She had spent most of her energy trying to figure out why she was behind in her grieving. She had buried her feelings and vowed to be strong because that’s how a person was supposed to be.

Now, in my office, stages, self-diagnoses and societal expectations didn’t matter. She was free to surrender to her sorrow. As she did, the deep bond with her little girl was rekindled. Her loss was now part of her story, one to claim and cherish, not a painful event to try to put in the past.

… THAT model (of grieving and getting over it) is still deeply and rigidly embedded in our cultural consciousness and psychological language. It inspires much self-diagnosis and self-criticism among the aggrieved. This is compounded by the often subtle and well-meaning judgment of the surrounding community. A person is to grieve for only so long and with so much intensity.

… When I suggested a support group, Mary rejected the idea. But I insisted. She later described the relief she felt in the presence of other bereaved parents, in a place where no acting was required. It was a place where people understood that they didn’t really want to achieve closure after all. To do so would be to lose a piece of a sacred bond.

It is no irony that the doctor who was able to help her had also lost his infant child just years before.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=btbE_9wY1nU&w=600]

And for Extra Credit:

The Green Bay Packers and the Settlers of Catan?

Sad But True: Boy Admits to Not Having Gone to Heaven

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply