A striking editorial by Lisa Miller appeared in New York Magazine last week about the recent death of Brittany Maynard, a 29 year old who had elected (and advocated for the right) to commit suicide after being diagnosed with terminal brain cancer. Miller is less interested in the ethics of Maynard’s decision and more interested in the unprecedented outpouring of adulation it has garnered. Miller tells us, “in the days since she died, [Maynard] has quickly become something more, especially in the ethereal space of social media, where she has risen to the status of a martyr-saint.” Strong words, and Miller rightly theorizes that there’s more going on here than public grief. In her view, the event exposes the current state of our ever-complicated relationship with death, in particular the little-l law against morbidity (akin to what RJ dissected in his piece about hospitals a while back). Thankfully Miller does not ‘blame’ Maynard remotely for what is a tragedy, no matter how you cut it. If anything, she points out how the sadness of the happenstance itself is compounded by the feebleness with which we try to manage it. Oy vey, ht ZW:

Part of the story is the simple tragedy — a young woman, so much of her life ahead of her. But the photo of Maynard that’s being passed around like an icon or a relic — Maynard holding a puppy and wearing a glorious, life-loving smile — shows more than a young woman in happier times. It tells us a lot about the way we relate to death and illness and bodily “dignity.” For starters, when did we first begin treating suicides in the face of terminal illness as heroic acts while viewing suicides facing other sorts of distress as essentially cowardly? The response to Maynard’s suicide demonstrates a peculiar preference that we in the secular West have for martyrs who are beautiful and young — perfect, like children plucked in innocence from life in a car or bicycle accident and memorialized with flower shrines by the side of the road…

Please don’t think I have anything to say about Maynard’s decision to end her life, because I don’t. I’m talking about a nation’s knee-jerk reverence for a young woman we never knew, a tidal wave of empathic grieving that allows us to dwell on the tragic injustice of untimely death while evading the grosser realities of death itself, which in the usual course of events involves shame, ugliness, and suffering. In my personal experience, death has been preceded by a fall on the kitchen floor and then hours of lying there waiting for help. It has meant hospital stays and surgeries and urgent cries for bedpans falling on inattentive ears… Ugliness and helplessness have always been understood to be the part of the deal. The Buddha said it straight-up — “All life is suffering” — and the Torah upholds as its most dignified death that of Abraham, who passed away when he was 175 years old, “at a good old age, an old man and full of years, and was gathered to his people.” Who knows how many weeks or months of decrepitude preceded this passage?

In the present-tense context, dignity seems to mean skipping all that, fast-forwarding past the utter dependence, the gibberish, and the bodily fluids — and the pain, of course, not to be discounted — to get straight to the end. Which is understandable, economical, modern, and, in a way, selfless. It’s not just about wanting to avoid the experience of suffering: It’s about not wanting to impose one’s suffering on others. Jesus, bleeding, cried out in agony and loneliness on the cross, and the earliest Christians loved their martyrs burnt, starving, or torn apart and chewed, but in the secular West, dignity has come to mean a kind of existential modesty, a wish not to be seen at one’s worst, at a moment when one might not have the wherewithal to retrieve an appropriate fig leaf for the indecent business that is death…

I’m not someone who believes things were better in the centuries before hospitals and vaccinations, or that there’s any right way to die. My mother was given large doses of morphine in her last days; she was grateful for it then, and I remain so today. Nor am I advocating, necessarily, the “natural” course of things in a world where technology irrefutably makes life — and death — better. I am saying that there’s something overly sanitized in our devotion to Maynard now. Look, she was so beautiful and, poof, now she’s gone. The dignity thing is a red herring, in my opinion, which privileges our voyeurism and consoles the control freaks among us, allowing us to fantasize that in death we can still be young and strong and in charge of outcomes and to look past the bare fact that life and death are unfair, disgusting, and heartbreaking sometimes, and there’s nothing at all to be done about that.

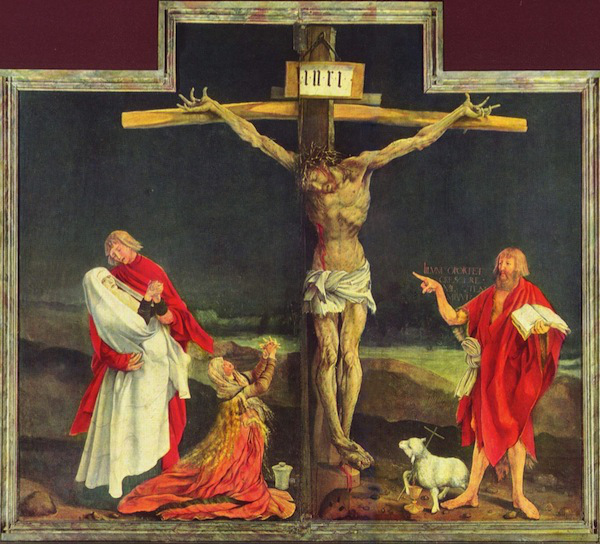

Again, we’re not talking so much about Maynard personally (who warrants nothing but our sympathy), so much as the lionizing response to her act we’ve seen in the media/social media. What Miller describes is a secularized theology of glory, where not even death is allowed to puncture our veneer of beauty or power or control, where “dignity” has becomes a synonym for strength, and self-respect cannot co-exist with weakness (a denial of reality which strikes me as the opposite of dignified). So Miller’s evocation of Christ is both appropriate and highly unexpected; it reminds me not just of the words of Gerhard Forde we posted yesterday about the world–i.e. us–resisting the reality of our limitations, but the story surrounding Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece. Jacob posted about it a few years ago (a portion of which made it into Tullian’s Glorious Ruin), and it positively floored me. So counterintuitive, especially in our present-day context.

Completed in 1515, just before the Reformation kicked off, the altarpiece was commissioned for the church hospital of St. Anthony in Colmar, France, which specialized in comforting those dying with skin diseases. While most of Gruenewald’s contemporaries were still depicting Calvary with post-Renaissance delicacy, his version was dark and borderline horrific: especially Christ’s smashed feet, His contorted arms, and His twisted hands. The cross is bowed to demonstrate the burden (of sin) Jesus is bearing. The most shocking part of the piece, however, is that Jesus Himself has a skin disease; His loincloth is the same as the wrappings worn by the hospital’s patients.

The altarpiece is a creation of such shocking intensity that many find it repulsive. I know I do. Yet the graphic nature serves to define and illustrate the Antonite brothers’ understanding of Christian ministry–ministry deeply informed by the theology of the cross. Apparently patients were brought before the piece in order to meditate on it as they died. The brothers were a quiet order, so no explanations were provided. There was no awkward chatter, no ‘sharing’, no halfhearted attempts to piously let God off the hook. There was just silence.

P.S. Here’s the sermon on “Personal Eschatology” that came together in the wake of this post:

COMMENTS

12 responses to “Existential Modesty and the Death of Brittany Maynard”

Leave a Reply

from Carlos Eirie, A Very Brief History of Eternity, p 108

A mere three years after he challenged Tetzel to a debate on indulgences with his 95 theses, Luther would be arguing that praying for the dead was as wrong as praying to the dead. To believe that the dead in heaven could pray for anyone on earth was dead wrong, as the pun would have it, or even worse. “The Scriptures forbid and condemn communication with the dead… For Luther, the communion of saints mentioned in the Creed was not to be understood as anything other than a eschatological hope.about the promised resurrection and the kingdom to come.

Luther summed it up in a sermon in 1522—-The summons of death comes to us all, and none of us can die for another. Everyone must fight his own battle with death by himself, alone. We can shout into each other’s ears, but everyone must himself be prepared for the time of death. I will not be with you then, nor you with me.

The praise for this young lady’s “very personal choice” to “end her on life with dignity” has been almost universal. When the Vatican bioethics official, Monsignor Ignacio Carrasco de Paula, dared to say it was “reprehensible” he was of course seen as a mean spirited old ass ( who probably had not run his comments by His Sweetness Pope Francis). This is because the only rule of morality that exits, and it may be the only absolute left in our time, is if I want to do it, and I am not harming others in my choice to do it, then it is grossly immoral to tell me I am wrong to do it, whatever “it” happens to be. We may say this is a tragic situation, which it as, and we may express genuine sorrow for this poor girl, but even with all that’ if we dare to violate this singular moral code by suggesting that “her choice” may be in any way open to questioning, we are going to have hell to pay.

Suicide in the western culture, or should I say, in America is most often described by the average person as the cowards way out. I always wince when I hear that judgment. I have always thought it was a brave thing to do, but the truth probable lies within the head of the person who contemplates or succeeds in the act. It is a lack of hope. A deep dark abyss where the light of hope has disappeared.

No. It isn’t brave. That account leaves the despairer in control as autocrat of her life and its limits, and therefore in bondage- not freedom. Do not enshrine death as one of the world’s goods.

If all she was trying to avoid was having the world see her without makeup, or being dependent on others, then I understand this view. But she described months of increasingly debilitating headaches, untouched by pain medication. Anybody who has laid in bed with a migraine, thinking they would do anything, anything to end the pain, cannot help but understand her decision. I don’t care what picture the media offers us, that is how I imagine her. Tears, vomit and unimaginable pain, days on end. And when someone from the Vatican questions her decision, I think we have a warped view of heroism. Suffering without purpose. The early church had to contend with some of its members actively seeking martyrdom, so enamored were they with the idea of victimhood. That is what comes to mind.

Yes, because she went public she became a hero. But every day in nursing homes people close to death simply refuse food and water. It hastens death, and thus the end of suffering. We don’t hear about them so they don’t rate as heroes. Are they wrong? People for whom pain medication still works — readily agree to be rendered unconscious when they are near death, to avoid pain. Is that wrong? Is it only wrong if when the pain medication fails to work. one asks for assistance to hasten the end of suffering?

I really think we can pull apart some of the important issues here from what happened in the media because she was young and chose (for her own reasons) to be very public with her story, with select views of her body in full vitality. But one doesn’t have to read far to learn that wasn’t the full picture.

The issue underlying this all is precisely “suffering without purpose.” We are not the arbiters of such a thing. It’s purposeless within a theology of glory, sure, but not within the real world where authentic human existence is normed by Christ’s life and death, which bore creaturely dignity by refusing to see pain and degradation as evils to be avoided at all costs. Of course we can all understand, but that doesn’t render her decision laudable at all. It completes the tragedy of her illness.

I’m afraid that sounds to me like abstract theological reasoning, and not like a real response to a young woman writhing in her bed.

I think of the objection to Jesus curing on the sabbath. At some point, the cry of suffering seemed to trump the point of sabbath, which as Jesus said, was not to be a law for its own sake, but for the sake of humanity.

I suspect we will not come to agreement about this.

I hope what I’ve said doesn’t come across as combative, my hope is that we may recognize we see more in common than was first apparent. I don’t think the pattern of Jesus’ life is abstract balm being poured on real wounds; I see that as the greatest encouragement to real sufferers in real, agonizing situations. As such, I don’t think the cry of suffering exposes a fault line in the vocation of humans to embody the same pattern of worship and death in the same way that it seems you do. If anything, it seems to me that offering death as a solution makes a show of having tamed or befriended the last enemy. I fear that saying otherwise is conceding too much ground to a man-centered view of what is real, leaving us the standard against which good news is measured. The tradition sees life as ecstatic gift regardless of circumstances a life finds itself within, and the only guarantee of that hope that makes it anything other than wishy-washy Stoicism is a suffering Son of God bearing abjection in himself. I hope that sheds more light on why I would argue that endurance is a gospel matter in this case rather than a Law.

Sorry Ian, I read this and think: maybe I’m just not this smart. Because if I’m writhing in pain, and going to die soon, I’d be all about “pass me the pills.” Pain killers, if possible, but if not, just make it stop.

I don’t mean to be combative either, but it reminds me of Job’s friend — which one was it? — “Job, these things are complicated, and deep, really deep, we can’t know the mind of God, and therefore we have to honor the mystery. . . ”

blah, blah blah is the way it sounds. Like a seminary student. Me: just hand me the damn pills. “A show of having tamed or befriended the last enemy,” is just not the way a person in pain speaks, reasons, or receives words. Put this in sentences you could deliver to Maynard and her family, and I’ll think a little more about it. But right now all I can hear is the shaming of someone who simply wants to stop the pain, in the name of a theological logic which would frankly escape me if it was my suffering or the suffering of someone I loved.

I guess at risk of sounding too sarcastic I’d point out that it’s God who in the end completely bypasses Job’s questions and waxes theological! I wouldn’t tell Brittany everything I typed out here; it was the two of us talking, not her and I. To Job I would speak gospel expecting impatience, all the while praying for supernatural patience on his part to hear and embrace what is said.

Ian, it seems to me that this is a sometimes problem with theology. I do realize we’re having a second order conversation about the theological meaning of suffering, but I can’t for the life of me imagine how one would offer this insight to a dying woman in pain. And increasingly, I’m becoming impatient with theology that I can’t form into sentences I’d actually use with human beings. And you and I hear the end of Job differently, I guess. I think I hear God sweep away the theological musings of the unhelpful friends in favor of an appearance.

We do hear the climax of Job differently, but it seems like that stems from eisegeting out the Law and focusing exclusively on gospel in God’s speech. I agree He sweeps away the unhelpful theologizing of Job’s “friends,” but He demonstrably does so by drawing attention away from Job’s troubles, not by smothering him with sympathetic, “Yeah, it would be better to die” consolation. I think we fundamentally disagree on what help is, because I think it’s more than simply bringing immediate relief to pain. I’m sorry we disagree, but Jesus’ motive in John 11:5-6 simply doesn’t make sense if your paradigm is the correct one.