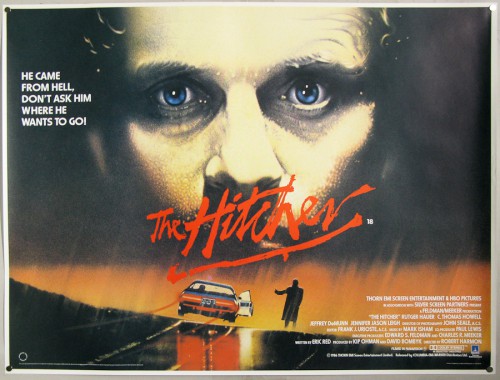

The second film selection for Blake & Ian’s four-part series comes from Blake’s selection of favorite horror films, the 1986 version of The Hitcher, starring Rutger Hauer, C. Thomas Howell and Jennifer Jason Leigh.

Blake:

Blake:

Jim Halsey: Why are you doing this to me?

John Ryder: You’re a smart kid…figure it out.

Whether it’s the rise of urban legends or the rise of actual incidents, hitchhiking is all but extinct nowadays. It seems to be another victim slain in the slow and continuous death of the old neighborly courtesies.

Hitchhiking is just one aspect of a wider American artistic landscape full of the open road–from Woody Guthrie to Jack Kerouac to Easy Rider. It is implanted in the very DNA of America all the way back to accounts of the Middle Passage and Alexis de Tocqueville. Something about the vastness of land between the East and West coasts, and the travel therein, captures the imaginations of Americans.

American road narratives are often naturalistic in their portrayal of the highways and the environments that surround it. The road narrative has become a stage for an almost Shakespearean drama of self-discovery. More often than  not, the results of that self-discovery are less enlightening and more frustrating, generally stemming from the raw constitution of the human nature–not only of the traveler, but also of the others he meets along the way. On some level, these asphalt stories always demand some form of blood offering.

not, the results of that self-discovery are less enlightening and more frustrating, generally stemming from the raw constitution of the human nature–not only of the traveler, but also of the others he meets along the way. On some level, these asphalt stories always demand some form of blood offering.

It is from within the darker underbelly of the road narrative that The Hitcher comes. Rutger Hauer—best known for his portrayal of Roy Batty in Blade Runner—plays the enigmatic hitchhiker, John Ryder, who seems to be on a murder spree on a stretch of desert road outside of California. The film picks up as a young man named Jim Halsey (played by Taps star C. Thomas Howell), who is delivering a car to San Diego from Chicago, stops to give Ryder a lift. What ensues from this initial meeting is one of the more visceral and relentless depictions of evil. As opposed to the “freedom” trope lent by many of the stories within the American road annals, the open here, with Ryder, strikes a note of deep claustrophobia.

The main thrust of the film is found in the psychological relationship that takes place between Ryder and Halsey, as their game of cat and mouse mounts to its violent conclusion. Halsey narrowly escapes Ryder’s first attempt to kill him by pushing him out of his car as he cruises down the highway, but Ryder does not fail at getting his prey. So, naturally, he begins to follow Halsey, toying with him from the backs of family vehicles before he lays waste to the families, basically daring Halsey to stop him. Ryder forces Halsey’s hand. He repeatedly tests Halsey’s self-preservation, his indifference to the lives of others. In order to avoid being killed, will Halsey forgo helping those who find themselves in the wake of a madman’s killing spree?

On top of that, Ryder does everything he can to make the cops suspect Halsey for all of the crimes. Ryder’s approach is ultimately to isolate Halsey and to make him suspect by all who might actually be able to save him. Those who continue to trust Halsey find themselves facing death, specifically Nash (Jennifer Jason Leigh), the young woman whom he meets at a roadside  diner. Once again, we find a direct challenge to the idea that good deeds deliver good results and bad deeds deliver bad results. Ryder does not create a karmic world for Halsey; in the world that Ryder inhabits, Halsey is damned if he does and damned if he doesn’t. If he chooses to do the right thing, then those who trust him get hurt and if he chooses the way of indifference and self-preservation then others get hurt.

diner. Once again, we find a direct challenge to the idea that good deeds deliver good results and bad deeds deliver bad results. Ryder does not create a karmic world for Halsey; in the world that Ryder inhabits, Halsey is damned if he does and damned if he doesn’t. If he chooses to do the right thing, then those who trust him get hurt and if he chooses the way of indifference and self-preservation then others get hurt.

The endgame for Ryder is self-discovery, the inherent darkness at the core of the human heart. The only way to stop Ryder is to become Ryder, and the final scenes of the film show Halsey bypassing justice for personal vendetta/vengeance. He has to become cold and unmerciful like Ryder in order to end the reign of terror. Mercy does not deliver the happy ending but could spell death.

One of the questions the viewer must then reckon with at the end of the film is: What is the better course of action in moments of violence? Do we become cold, indifferent, or unmerciful towards the aggressor in order to end their reign of terror or do we go by mercy—facing certain suffering and/or death? Or, as more ancient wisdom put it: For what does it profit a man to gain the whole world and forfeit his soul?

There are no satisfying answers to those questions, at least not in the here and now. This is why The Hitcher succeeds in creating a desolate world where even good deeds can reap bad consequences and the only good that can incarnate its universe is a blood sacrifice across the two lanes of blacktop. A sacrifice not found within the scheme of the film. Chaos and violence, instead, overtake the deserted landscape.

Ian:

John Ryder: “I want to die.” Say it.

Jim Halsey: I don’t know if I can say that.

John Ryder: Sure you can. Repeat after me: “I… Want… To… Die.”

The Hitcher depicts evil as impelled by its own death wish and seeking its end at the hand of its victims. The purity of John Ryder’s devotion to senseless butchery instantiates what T.F. Torrance called “the abysmal irrationality of evil”, that incomprehensible urge to corrupt, destroy, and die for no other reason than to defy God. What logic could inform how Ryder forces his victims to verbalize his own desire to die before dispatching them as substitutes so that he can continue the orgy of death? Can Ryder’s headlong plunge into his own destruction be anything but the meltdown of the short-circuiting imago Dei? Ryder’s death binge simultaneously gives evil a terrifying banality and an unfathomable, metaphysical menace.

The Hitcher depicts evil as impelled by its own death wish and seeking its end at the hand of its victims. The purity of John Ryder’s devotion to senseless butchery instantiates what T.F. Torrance called “the abysmal irrationality of evil”, that incomprehensible urge to corrupt, destroy, and die for no other reason than to defy God. What logic could inform how Ryder forces his victims to verbalize his own desire to die before dispatching them as substitutes so that he can continue the orgy of death? Can Ryder’s headlong plunge into his own destruction be anything but the meltdown of the short-circuiting imago Dei? Ryder’s death binge simultaneously gives evil a terrifying banality and an unfathomable, metaphysical menace.

Particularly disturbing is his attachment to Jim Halsey: “I want you to stop me,” he tells Jim. Why? Simply to be the deliverer of his own suicide? Or to become his replacement? Whichever it is, Ryder spends the film delighting in Jim’s forced descent into ignominy and violence and relishing the interchangeability developing between them. But this is precisely where sin’s death drive sabotages itself: through the agony and degradation he’s been subjected to, Jim understands Ryder in a way no one else in the film is able to, and is thus the only character who doesn’t underestimate him. The film is left rather open-ended, so it’s difficult to state with finality whether Jim has succumbed to Ryder’s depravity or if he’s come to know it in a profoundly intersubjective manner which grants him the necessary insight to stop him. I say this because there is a point to be made here regarding Jim’s corruption at Ryder’s hands, how the film’s final sequence can carry overtones of revenge rather than justice. There is a dehumanization that has taken place before our eyes, but does it have the final word here? If simul justus et peccator is a reality, isn’t there more than just a possibility that revenge and justice coincide in Ryder’s death?

In light of this, I would want to go a step further than Blake and say that the church (and the world) needs not only Niemollers and ten Booms- we also need Bonhoeffers. Without both foci, the ellipse wobbles out of control. It’s not that we need aggressive, militaristic “heroes”: far from it. But we will need those servants who will consecrate themselves to actively unseat the inveterate foes of grace, those foes the world won’t recognize for what they truly are.

You can view the whole film below:

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6WuKEAtNenY&w=600]

COMMENTS

2 responses to ““Just The Two Of Us”: Robert Harmon’s The Hitcher (1986)”

Leave a Reply

“The only way to stop Ryder is to become Ryder, and the final scenes of the film show Halsey bypassing justice for personal vendetta/vengeance. He has to become cold and unmerciful like Ryder in order to end the reign of terror. Mercy does not deliver the happy ending but could spell death.”

Scorsese depicts something very similar in his version of Cape Fear (1993). Nick Nolte’s character essentially has to “become” the very base, crude, uncouth and violent Max Cady (DeNiro) in order to defeat him.

Interesting review – cool series, guys!

God this film is awesome, I can’t stop watching it, it just gets into your very soul, I so feel for poor, sweet and innocent Jim, and as for Ryder (Hauer ) wow…he’s everything…mysterious, deadly, calm, brooding, angry, sinister, captivating..and so bloody (pun intended) gorgeous!! Such a good looking unusual looking guy back in the day was Rutger Hauer. Those eyes!