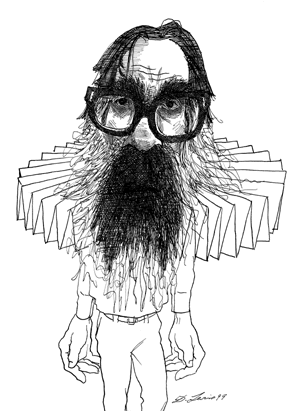

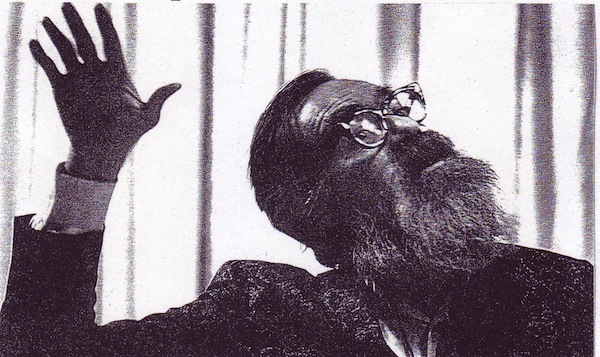

From the great poet’s 1970 interview with The Paris Review, shortly after the second volume of The Dream Songs was published. The ‘treatment’ to which Berryman refers is alcohol rehabilitation, for which he was hospitalized numerous times during that year. Thus the references to ‘leave’ being rescinded, etc. This interview was conducted less than 18 months before he tragically jumped to his death in Minneapolis. It’s worth reading the whole thing, if only to absorb the footnotes Berryman made a few months later about the various delusions he had expressed, ht MS:

INTERVIEWER

INTERVIEWER

There has always been a religious element in your poems, but why did you turn so directly to religious subject matter in these poems?

BERRYMAN

They are the result of a religious conversion which took place on my second Tuesday in treatment here last spring. I lost my faith several years ago, but I came back—by force, by necessity, because of a rescue action—into the notion of a God who, at certain moments, definitely and personally intervenes in individual lives, one of which is mine. The poems grow out of that sense, which not all Christians share.

INTERVIEWER

Could you say something more about this rescue action? Just what happened?

BERRYMAN

Yes. This happened during the strike which hit campus last May, after the Cambodian invasion and the events at Kent State. I was teaching a large class—seventy-five students—Tuesday and Thursday afternoons, commuting from the hospital, and I was supposed to lecture on the fourth Gospel. My kids were in a state of crisis—only twenty-five had shown up the previous Thursday, campus was in chaos, there were no guidelines from the administration—and besides lecturing, I felt I had to calm them, tell them what to do. The whole thing would have taken no more than two hours—taxi over, lecture, taxi back. I had been given permission to go by my psychiatrist. But at the beginning of group therapy that morning at ten, my counselor, who is an Episcopalian priest, told me that he had talked with my psychiatrist, and that the permission to leave had been rescinded. Well, I was shocked and defiant.

I said, “You and Dr. So-and-So have no authority over me. I will call a cab and go over and teach my class. My students need me.”

He made various remarks, such as “You’re shaking.”

I replied, “I don’t shake when I lecture.”

I replied, “I don’t shake when I lecture.”

He said, “Well, you can’t walk, and we are afraid you will fall down.”

I said, “I can walk,” and I could. You see, I had had physical permission from my physician the day before.

Then the whole group hit me, including a high official of the university, who was also in treatment here. I appealed to him, and even he advised me to submit. Well, it went on for almost two hours, and at last I submitted—at around eleven-thirty. Then I was in real despair. I couldn’t just ring up the secretary and have her dismiss my class—it would be grotesque. Here it was, eleven-thirty, and class met at one-fifteen. I didn’t even know if I could get my chairman on the phone to find somebody to meet them. And even if I could, who could he have found that would have been qualified? We have no divinity school here. Well, all kinds of consolations and suggestions came from the group, and suddenly my counselor said, “Well, I’m trained in divinity. I’ll give your lecture for you.”

And I said, “You’re kidding!” He and I had had some very sharp exchanges. I had called him sarcastic, arrogant, tyrannical, incompetent, theatrical, judgmental, and so on.

He said, “Yes, I’ll teach it if I have to teach it in Greek!”

I said, “I can’t believe it. Are you serious?”

He said, “Yes, I’m serious.”

And I said, “I could kiss you.”

He said, “Do.” There was only one man between us, so I leaned over and we embraced. Then I briefed him and gave him my notes, and he went over and gave the lecture. Well, when I thought it over in the afternoon, I suddenly recalled what has been for many years one of my favorite conceptions. I got it from Augustine and Pascal. It’s found in many other people, too, but especially in those heroes of mine. Namely, the idea of a God of rescue. He saves men from their situations, off and on during life’s pilgrimage, and in the end. I completely bought it, and that’s been my position since…

Later in the interview, Berryman remarked about where he hoped to go next in his artistic life — and what he says translates to the religious life quite seamlessly:

I have a tiny little secret hope that, after a decent period of silence and prose, I will find myself in some almost impossible life situation and will respond to this with outcries of rage, rage and love, such as the world has never heard before. Like Yeats’s great outburst at the end of his life. This comes out of a feeling that endowment is a very small part of achievement. I would rate it about fifteen or twenty percent. Then you have historical luck, personal luck, health, things like that, then you have hard work, sweat. And you have ambition. The incredible difference between the achievement of A and the achievement of B is that B wanted it, so he made all kinds of sacrifices. A could have had it, but he didn’t give a damn. The idea that everybody wants to be president of the United States or have a million dollars is simply not the case. Most people want to go down to the corner and have a glass of beer. They’re very happy. In Henderson the Rain King, the hero keeps on saying, “I want. I want.” Well, I’m that kind of character. I don’t know whether that is exhausted in me or not, I can’t tell.

But what I was going on to say is that I do strongly feel that among the greatest pieces of luck for high achievement is ordeal. Certain great artists can make out without it, Titian and others, but mostly you need ordeal. My idea is this: The artist is extremely lucky who is presented with the worst possible ordeal which will not actually kill him. At that point, he’s in business. Beethoven’s deafness, Goya’s deafness, Milton’s blindness, that kind of thing. And I think that what happens in my poetic work in the future will probably largely depend not on my sitting calmly on my ass as I think, “Hmm, hmm, a long poem again? Hmm,” but on being knocked in the face, and thrown flat, and given cancer, and all kinds of other things short of senile dementia. At that point, I’m out, but short of that, I don’t know. I hope to be nearly crucified.

INTERVIEWER

You’re not knocking on wood.

BERRYMAN

I’m scared, but I’m willing. I’m sure this is a preposterous attitude, but I’m not ashamed of it.*

(That final asterisk indicates what Berryman considered, with five months hindsight, to be a delusion – ha!).

COMMENTS

One response to “John Berryman’s Second Conversion”

Leave a Reply

Brilliant, brave:

“The artist is extremely lucky who is presented with the worst possible ordeal which will not actually kill him. At that point, he’s in business.”

Thanks for posting this link.