This one comes to us from the fascinating mind of Jeremiah Lawson, aka Wenatchee the Hatchet:

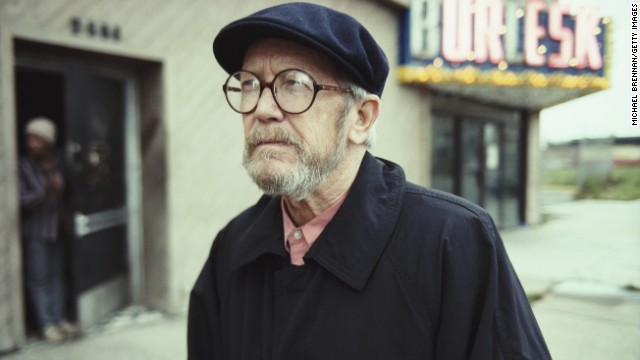

The Library of America recently rolled out the first installment in a set of Elmore Leonard novels that are now part of their line-up. To mark the occasion, critic and columnist Terry Teachout has revisited his skepticism about Elmore Leonard being regarded as a member of a literary pantheon. This isn’t to suggest that Teachout isn’t a fan of Leonard’s work. This is the same man who published a fine biography on Duke Ellington last year. Instead, he is concerned that our efforts to exegete pop culture may have come with a price.

Teachout goes on to highlight the most talked-about television shows of the last few years, all of which have been melodramas and thrillers:

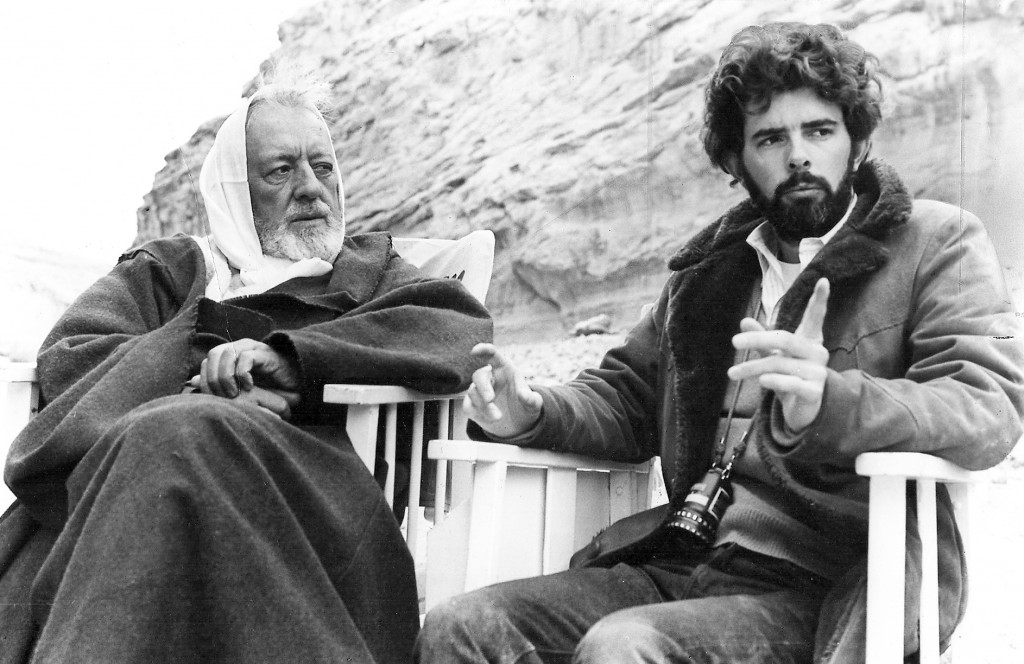

The problem is not that pop culture doesn’t deserve to be taken seriously. It’s that a culture totally dominated by popular art is by definition limited. Let’s go back to Mr. Leonard’s novels for a moment. Sure, they’re superbly crafted, but they’re all pure melodramas whose subject is crime, with a little romance thrown in for seasoning. So, almost without exception, are the television series that have come of late to be widely regarded as the best that America’s storytellers have to offer. From “Hill Street Blues” to “The Sopranos” to “Breaking Bad,” these series are all thrillers of one kind or another. To be sure, they use the time-honored conventions of genre fiction to explore many other aspects of American life—but in the end, somebody always gets shot, just as a pop song, no matter how good it may be, is almost always three minutes long…

Once again, it’s not my purpose to demean pop culture. I think that most of the best movies made in America in the 20th century were crime dramas, screwball comedies and westerns. But there’s more to life than getting your head blown off in a drug deal, and more to be said about love than can be crammed into a 32-bar ballad.

Ironically, when shows like The Sopranos or Breaking Bad or Game of Thrones become the talk of critics and viewers alike we may be embracing the HBO or highbrow iteration of material that has not so much left behind its pulpier roots so much as found a way to make those roots more “presentable”. A Bryan Cranston can play Hal in a sitcom, an animated Jim Gordon, and Walter White and still come across as respectable. And yet, the respect goes to Cranston, sometimes over against the roles he chooses to play. We’ll give props to Cranston without necessarily saying Malcolm in the Middle is high art.

Of late, Teachout has also noted in his blogging the rise of what he calls the “commodity musical”, a musical often adapted from a popular film or television. While adapting popular existing material into a musical production is nothing new, Teachout has worried that the newer commodity musical is more slavishly devoted to the adaptation of its source material than musicals that did the same kind of work in earlier generations. Whether in Hollywood’s sequel-seeking accounting or in Broadway’s seeking success in adapting Hollywood, it may be that popular culture has been generating a self-sustaining feedback loop that Teachout and others can be legitimately worried about. Joseph Campbell’s monomyth may so permeate our pop culture that when it reaches its end-point we will just be stuck with one story we’ve seen a thousand times.

Furthermore, there’s a sense in which the one story and ethic we consider safe enough to put in all our popular media is going to be the one we consider so safe that no one should be offended by it. That’s why a critique of the “everyone is a special snowflake” ethic in kids movies, or the idea that you should be true to yourself and you can do anything you want to, should be seen less as trite pulp for kids and more as a reflection of adult expectation.

On another level, as critics and viewers begin to get the sense we’ve seen it all before, Teachout points out a potential drawback for the Broadway musical these days, “Another reason [for the rise of the commodity musical] is that Broadway songwriters no longer have a common musical language on which to draw.”

For a time a hybrid of jazz, light opera and Tin Pan Alley could provide a cohesive musical vocabulary for 20th century American musical theater. But with the rise of rock and roll that common language became obsolete–or it might be better to say the delicate balance of then-current popular styles became obsolete. The 20th century bore witness to such a colossal fragmentation of musical style in the industrial and post-industrial West that a consolidation of form and style in music may not be practical (or desirable). For fans of music it can be great, but for fans of musical theater it may be a challenge.

For a time a hybrid of jazz, light opera and Tin Pan Alley could provide a cohesive musical vocabulary for 20th century American musical theater. But with the rise of rock and roll that common language became obsolete–or it might be better to say the delicate balance of then-current popular styles became obsolete. The 20th century bore witness to such a colossal fragmentation of musical style in the industrial and post-industrial West that a consolidation of form and style in music may not be practical (or desirable). For fans of music it can be great, but for fans of musical theater it may be a challenge.

What might a long-term solution be? Not necessarily the consolidation of all popular song into the same four chords we hear in songs ranging from “Let it Be” to the chorus of “Let it Go” (I-V-vi-IV for those who mind the scores). Why? Because we have become such voracious listeners to popular music there’s a serious risk of anticipating all the formulae and their corresponding attempts to emotionally manipulate us into certain moods by the time we hear the first four seconds of a song.

Perhaps Teachout has been indirectly hinting at a potential solution. He worries that our focus on popular culture is coming at the expense of high culture, but he also doesn’t want either to be ignored. What has the historic bridge between the highbrow and lowbrow been? Why, the middle brow of course. The mediator between the head and the hands must be the heart and all that.

Teachout recently wrote in memory of a singer the majority of us will not have heard of, let alone heard, but Teachout’s summation of the singer telegraphs what he believes we need in each generation.

He [John McCormack] was, in short, a middlebrow in the very best sense of the word, an artist who was at once serious and popular, who believed in his bones that those two things were not mutually contradictory, and who also believed that he could ennoble his popular audiences by introducing them to serious music.

COMMENTS

One response to “Terry Teachout on Pop Culture and the Need for a Balance Between High and Low”

Leave a Reply

Teachout mentions Yeats, but as I’m sure he knows, another Irish highbrow, James Joyce, was a friend of McCormack’s, and even sang with him once.

I think it’s possible to have highbrow tastes and middlebrow understanding – also highbrow understanding and middlebrow tastes.