The story begins with the man who would become Deputy Clem on Bonanza for thirteen years, Bing Russell (father of Kurt Russell), baseball wash-up and “plumber actor,” as his son describes him, the lowdown scoundrel shot first in swinging-door tavern fights. “I mean that lovingly…he went to work. Boom. Boom. Boom…my dad got killed one hundred twenty six times, I think it was. He did over 800 television shows.”

Beneath his love for acting, though, was an older and deeper love for baseball. And as Bing’s acting career began to dry up after Bonanza was cancelled in 1972, so too, was a AAA minor league ball team in Portland, Oregon, whose game attendance had dwindled to peanuts over their 70-year stint in the Rose City. As the Portland Beavers became the Spokane Indians, Bing decided to stir something up. As the local newspapermen of the day said, “It was open territory. And it didn’t look like there were any prospects of anybody stupid enough to show up.” It was here in the general disinterest of the town that the Hollywood huckster devised to create an independent ball club. As for the then-provincial Portlandians (“There was nothing going on in Portland, Oregon at that time”), there was nothing but wisecracks and skepticism: “Suddenly here comes this actor from Southern California…and you begin to wonder, maybe it was a joke or a promotion or he had some side angle.”

It certainly didn’t help the cause when, instead of signing up with the Pacific Coast League’s professional farm system, Bing Russell’s Portland Mavericks were going to be independent. That meant that, instead of being the affiliate of a parent club—the Yankees or the Padres or the Dodgers—the Mavericks were on their own. Everything they did, every dollar they spent, they were accountable for. There was no Big League lawyer, no Upstairs Accountant to steer them from the fire. In the days of Professional Baseball (the film makes clear distinctions between baseball and Baseball—the Major League Institution), it was financial suicide: to build an independent ball club of which there were no others in the country, with more overhead to manage than any other general manager in the country, and do so in a town whose citizens had more or less waved sayonara to baseball less than a year ago. To your average paper reader, it was a reckless gamble by a hobby-horse actor. It was more Portland than Portland.

And on the flip-side, the wacky underbelly from which Bing chose to see things, Portland’s Mavericks were accountable to nobody. In the minor league farm system, a team was always losing their best players to the higher rung of their affiliation. A minor league town never knew who their third basemen was because, if he proved any good, he’d be gone, moved up in a matter of weeks to his major league destination. While Bing was responsible to scout, sign and pay his players by himself, he was also free to suppose his Portland Mavericks weren’t going anywhere. They were there because, well, they were there.

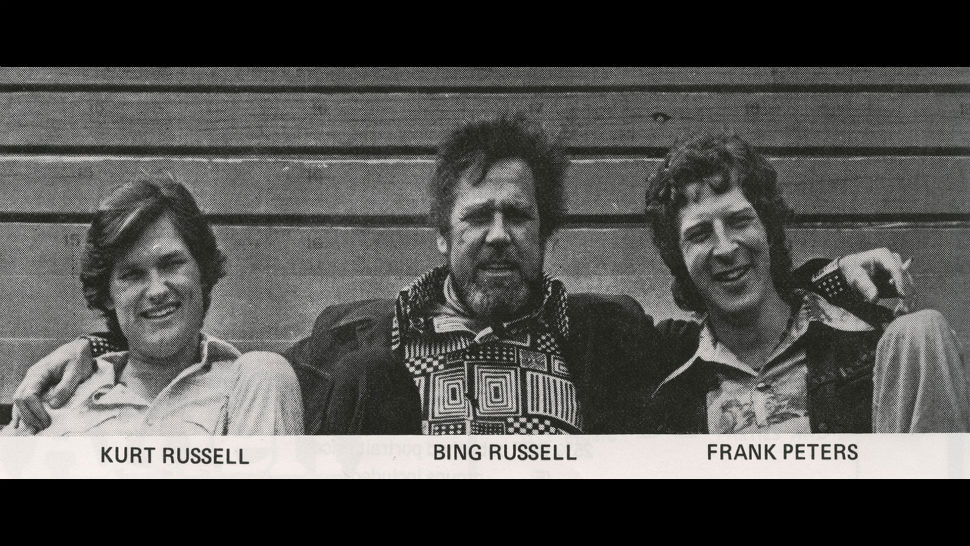

And so it went. An independent baseball team, up against the powers of Baseball. And to scale up the rapscallion nature of the deal, Bing decided to field his disciples by way of open tryouts in the classifieds of The Sporting News. His choice for a manager was (don’t laugh), Frank “The Flake” Peters, who rode the pine his entire career as a backup for the legendary Brooks Robinson (the greatest defensive third basemen in baseball history) for his 16 years in the Baltimore Orioles farm system. Now owning a local restaurant, he found a new avenue:

“My goal was to be like Babe Ruth or something like that. So I said to myself, ‘Well, it doesn’t look I’m going to be what I originally anticipated being in this game, so I’m going to enjoy it, and play it on my own terms,’ which ended up being playing in Portland.”

Amid the criticism, Bing and The Flake moved right towards the laughability of their pursuit: “You never know what we’re going to find. Show us for the fools that we are.” In an open tryout where 40 or 50 would have been expected, 300 showed. Men hitchhiked cross-country, sold possessions, slept in cars to try out for the team. Here’s what The Flake said:

“Everybody there had been rejected. I, personally, my career had ended. I felt I had been rejected. All the players, they felt that they had been rejected. And maybe even Bing in Hollywood had felt he’d been rejected…it became apparent that Bing had been putting all these parts together. So Bing was literally casting a play…and you knew what your role was. You knew how you fit in.”

The footage of the tryouts alone are heartening—to see potbellied bikers and shirtless infielders and handlebar mustaches, within this forgotten sporting sanctuary, abandoned to the ridicule of its own town, yet by its size still somehow conjuring the power of a professional sport. And to see this professional ballfield plundered by a community of bad throws and missed groundballs and loping outfield chases—it’s so blessed endearing. It might be the only try-out you could see yourself wanting to be a part of. Bing and company brought on some thirty players, all of them unsuitable for major league baseball, some even unsuitable for baseball, but brought on the team because Bing knew they needed another chance. When Joe Garagiola brought national television to the team’s tryouts, The Flake had this to say:

Garagiola: What are you looking for out here?

Frank Peters: I’m looking for someone who can play for the Mavs and not necessarily a big leaguer. What we’re looking for is a ball player that organizations, for whatever reason, whatever they choose, do not think they can play in the big leagues. These are the guys who wish they could and haven’t been able to.

Among this crew of castoffs: “Swannie” the left-handed catcher (since the 1900 Boston Beaneaters, there never has been a starting left-handed catcher in MLB history). The Oregon newspaper called it “The Mavericks’ Left-Handed World.” Larry Colton, high school English teacher with Charles Manson locks and beard, now a pitcher. Eleven-year-old Todd Field (now an Oscar-winning movie director), a bat boy. Lannie Moss, the first female General Manager, aged 24, who had to sing the national anthem when their singer failed to show. Reggie Thomas, the Smash Williams star, with the drama to go with it, who asked for (and received) a car to drive him into the stadium each game. When asked why Reggie was getting a car to drive him a block to the stadium, Bing told the batboy, “Because Reggie needs that.” Jim Bouton, the only major league veteran—who pitched in the World Series for the Yankees, and then wrote an exposé about the dark side of professional Baseball, was ostracized by the major league—found a new home with the Mavs.

And then there’s Joe Garza, who became the team’s mascot, Jogarza—the “target” that the city of Portland could get behind. Jogarza—a red bandana-ed, mustachioed infielder swinging an ignited broom on top of the dugout—became a verb for a series sweep, the vocabulary of the Mavs fun world winning out.

But the Real McCoy was Bing himself. More than an owner, much more a kind of juvenalian father figure, Bing was a wild shepherd of the strangest breeds. From the former batboy: “He would keep guys on the roster who had no business being there. It’s f***ing nuts. What’s a guy running a class A baseball team doing keeping 30 guys on a roster. What he’s doing is he personalized the game in a way to where if you couldn’t find yourself in one of those players, you didn’t belong at that ballpark.” The film portrays an incisive even-headedness that was so even it made his decisions seem bizarre. He was “the most fair and talented observer of a player that anyone ever saw. People said, ‘This guy can read a ball player as good as anybody.’”

The total package was a team of nitwits and ragamuffins winning baseball games in the most frustrating way possible: being themselves! Drinking beer in the locker room, pulling their pants down on the field, sticking a reprobate finger in the light socket of Major League Expectations:

The Eugene Emeralds, the Cincinnati Reds affiliate, everybody’s stirrups were the exact same length. The shaving. The haircuts. It was much more regimented—the organizations wanted to set the tone. Most of the Mavericks had a little bit of a paunch. They led the league in stubble. And many of the guys literally had toes through their spikes, so (everyone) was stunned, saying ‘What kind of team is this?’…There were no press handlers, there was no groomed image. It was just these furry, hairy, funny, f***ing great bunch of guys…

Everyone knows the underdog, second-chance story is not long for this world, and I’ll leave it to the film to unroll the rest, but the Mavs weren’t just funny and scrappy, they were good. The film shows a clip from the Los Angeles Times: “The Portland Mavericks are bruising, belching proof that truth is stranger than fiction.” What fiction, you ask? The film suggests that it’s the fiction of Big League Management, an empire built on right-arm aces and press handlers and regimented sock lengths. Sure, a salaried roster of healthy horses is going to win ball games. Everyone knows that. But the surprising thing, that no one really wants to know, is what can happen when a living, breathing second chance steps on the mound. The wild provisions of grace there can make the whole Establishment look bad.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RA76b5Hhvxg&w=600]

COMMENTS

4 responses to “The Only Left-Handed Catcher (Ever)”

Leave a Reply

Oh man oh man – I watched it last night after your rec and haven’t been this delighted by a sports doc since Undefeated. The ending may have been inevitable (though not without one final middle finger from Bing!) but I’m glad I live in a world where the Mavs happened in the first place. It was like AA translated into sports (with better facial hair!). Talk about a fellowship of outcasts. Just amazing.

And how about the Big League Chew connection?! I almost fell out of my seat.

P.S. You’ve got to review some of Jim Bouton’s prose next. What a character!

On the cusp of football season here in Title Town, this movie was a breath of fresh air. And of course the team had to be in Portland … where else? Maybe the Mavericks invented weird. Like DZ the Big League Chew reference was mind “blowing”! Thanks

This is the good stuff. Thanks much.