The New Yorker may have published the definitive word on parenting think-pieces a few weeks ago, but apparently the memo didn’t make it across town to The Times. Which is fortunate, since there’s quite a bit to be gleaned from Adam Grant’s recent “Raising a Moral Child”. If most parenting articles tend to focus on things like anxiety and self-image and work ethic, Grant gives us a helpful survey of current social science on how/where kids develop conscience and compassion and kindness. He begins by telling us that “when people in 50 countries were asked to report their guiding principles in life, the value that mattered most was not achievement, but caring.” Not surprisingly, most of the studies he cites boil down to how one separates behavior from identity, what you do from who you are, etc. When it comes to positive behavior–sharing for example–children respond better to being praised for “being a good sharer” than doing “a good job at sharing”. They prefer the noun to the verb, you might say. Shades of imputation abound:

Many parents believe it’s important to compliment the behavior, not the child — that way, the child learns to repeat the behavior. Indeed, I know one couple who are careful to say, “That was such a helpful thing to do,” instead of, “You’re a helpful person.” But is that the right approach? The children were much more generous after their character had been praised than after their actions had been… When our actions become a reflection of our character, we lean more heavily toward the moral and generous choices. Over time it can become part of us… Praise appears to be particularly influential in the critical periods when children develop a stronger sense of identity.

But this is where it gets interesting. When it comes to negative behaviors, the inverse appears to be true, i.e. it’s (obviously) more effective to communicate to a child that they’ve made a mistake, rather than that they are a mistake. Which is where the key difference between shame and guilt comes in (paging Brene Brown!):

When children cause harm, they typically feel one of two moral emotions: shame or guilt… Shame is the feeling that I am a bad person, whereas guilt is the feeling that I have done a bad thing. Shame is a negative judgment about the core self, which is devastating: Shame makes children feel small and worthless, and they respond either by lashing out at the target or escaping the situation altogether. In contrast, guilt is a negative judgment about an action, which can be repaired by good behavior. When children feel guilt, they tend to experience remorse and regret, empathize with the person they have harmed, and aim to make it right.

…the psychologist Nancy Eisenberg suggests that shame emerges when parents express anger, withdraw their love, or try to assert their power through threats of punishment: Children may begin to believe that they are bad people. Fearing this effect, some parents fail to exercise discipline at all, which can hinder the development of strong moral standards.

Grant goes on to mention ‘expressing parental disappointment’ as the best way of falling on the guilt side of the equation, which is curious to say the least. To these ears that sounds like a surefire recipe for shame. Oh well.

Perhaps this is where Christianity has a contribution to make, or at least, where it might help us resolve such conflicting conclusions. The proclamation that one’s identity has been securely bestowed by someone-who-is-not-you allows for the separation that Grant is endorsing in both of its forms, yet without giving either behavior or character the final word. Yes, we affirm that character precedes and produces behavior, a good tree bears good fruit and so on. We also acknowledge the temptation–indeed, the danger–of ‘mapping-back’ (ht EKR), of using the fruit to draw conclusions about the tree.

I’m reminded of Jacob Smith’s stellar session in NYC a few weeks ago, in which he spoke about the unpredictable (and frustrating!) lemon tree in the garden of his childhood home in Arizona. Some years it bore tons of fruit, some years it bore almost none at all, some years it flourished, some years it shriveled – the one thing that never changed was that it was a lemon tree.

Again, this does not mean that shame and self-loathing are somehow binding for those whose behavior (or parenting habits!) fit a less flattering profile. In fact, quite the opposite. The question of the “core self”–i.e. who we are before God–has already been answered. That Easter-shaped ship has sailed, thank God. Our transgressions, be they big or small, no longer serve as clues one way or the other. If it sounds paradoxical, maybe it is. As our glossary puts it, “Christians are two things at the same time, both enduringly sinful and completely forgiven and justified by the imputed righteousness of Christ. Their identity is dual. This is not a half-and-half relationship; it is 100% and 100%. Paradoxically, we are fully saved and made righteous in Christ, and at the same time we are still the same old sinner we used to be.”

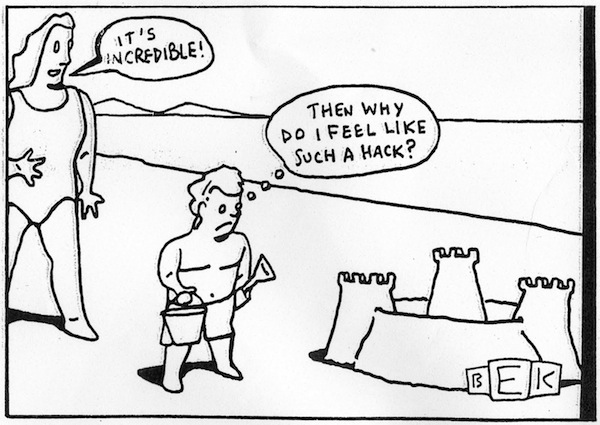

Grant ends his short article with a comment on the limits of exhortation when it comes to moral behavior. It is sad yet telling that he uses the word ‘preaching’ to signify ‘intentional moralizing’, but his main observation stands. Telling people to act morally does not inspire them to do so. At first blush it might sound like he’s pushing something akin to that old platitude about “preaching the gospel always, if necessary use words”, yet when read through the lens of the preceding paragraphs about the power of words to ‘name’, well, there may be some real implications for actual preaching, aka the unqualified proclamation of the gospel:

Grant ends his short article with a comment on the limits of exhortation when it comes to moral behavior. It is sad yet telling that he uses the word ‘preaching’ to signify ‘intentional moralizing’, but his main observation stands. Telling people to act morally does not inspire them to do so. At first blush it might sound like he’s pushing something akin to that old platitude about “preaching the gospel always, if necessary use words”, yet when read through the lens of the preceding paragraphs about the power of words to ‘name’, well, there may be some real implications for actual preaching, aka the unqualified proclamation of the gospel:

In a classic experiment, the psychologist J. Philippe Rushton gave 140 elementary- and middle-school-age children tokens for winning a game, which they could keep entirely or donate some to a child in poverty. They first watched a teacher figure play the game either selfishly or generously, and then preach to them the value of taking, giving or neither. The adult’s influence was significant: Actions spoke louder than words. When the adult behaved selfishly, children followed suit. The words didn’t make much difference — children gave fewer tokens after observing the adult’s selfish actions, regardless of whether the adult verbally advocated selfishness or generosity. When the adult acted generously, students gave the same amount whether generosity was preached or not — they donated 85 percent more than the norm in both cases. When the adult preached selfishness, even after the adult acted generously, the students still gave 49 percent more than the norm. Children learn generosity not by listening to what their role models say, but by observing what they do.

The most generous children were those who watched the teacher give but not say anything. Two months later, these children were 31 percent more generous than those who observed the same behavior but also heard it preached. The message from this research is loud and clear: If you don’t model generosity, preaching it may not help in the short run, and in the long run, preaching is less effective than giving while saying nothing at all.

Of course, some might say that, lurking beneath all these insights–sympathetic as they may be–is one more road-map in a world full of crashed cars, one more promise that with enough foresight and knowledge we can engineer an infallible child (or parent), one more denial of Good Friday and hedge against the new–not better–life we heard about this past Sunday. Which means it might be time to re-read that New Yorker article. That, or Romans.

COMMENTS

2 responses to “Moral Children and the Parents Who Praise Them”

Leave a Reply

Really interesting DZ. The expression of disappointment by a parent (at least in my experience on both sides of the relationship) is indeed crushing. Even if the parent seeks to specifically express disappointment in the behavior and not the character, the child’s reaction doesn’t seem to suggest they’re able to grasp that “this is a guilt moment, not a shame moment”. That’s a lot to ask a kid to process.

This is where Sally Lloyd Jones and the “Jesus Story Book Bible” is an example (one of many) of, as you suggested, how Christianity might have “a contribution to make”. Speaking gently with our children, during the aftermath of our “less than stellar moments”, about our mutual need for a Savior certainly seems (logically – dare I say) to be an antidote worth trying.

Great post David and great point Howie.