It’s become fashionable in some Protestant circles to talk about inspiring virtue not through dry rules or frustrated self-discipline, but through a vision of the moral life. ‘Living into the Kingdom’, or looking at a beautiful vision of God’s restoration in the eschaton and ‘mapping backwards’ (see Ethan’s TFA piece in The Mockingbird) to see how we act in light of God’s redemption are ideas and phrases enjoying broad use in American Christianity. Even those who haven’t read the intellectual mainstays of this idea (Wright, Smith, etc) still implicitly think this way. I know I’d rather show my children Caillou’s unflagging instinct for being a good friend than I would show them Rust’s brand of friendship on True Detective. And there’s something to be said for instilling in children a sense of the goodness of, well, goodness. The idea that seeing the good inspires us to do it also enjoys high credibility in pagan and secular philosophy: Plato’s Meno, a foundational text for Western thought, endorses this idea – sort of.

It’s become fashionable in some Protestant circles to talk about inspiring virtue not through dry rules or frustrated self-discipline, but through a vision of the moral life. ‘Living into the Kingdom’, or looking at a beautiful vision of God’s restoration in the eschaton and ‘mapping backwards’ (see Ethan’s TFA piece in The Mockingbird) to see how we act in light of God’s redemption are ideas and phrases enjoying broad use in American Christianity. Even those who haven’t read the intellectual mainstays of this idea (Wright, Smith, etc) still implicitly think this way. I know I’d rather show my children Caillou’s unflagging instinct for being a good friend than I would show them Rust’s brand of friendship on True Detective. And there’s something to be said for instilling in children a sense of the goodness of, well, goodness. The idea that seeing the good inspires us to do it also enjoys high credibility in pagan and secular philosophy: Plato’s Meno, a foundational text for Western thought, endorses this idea – sort of.

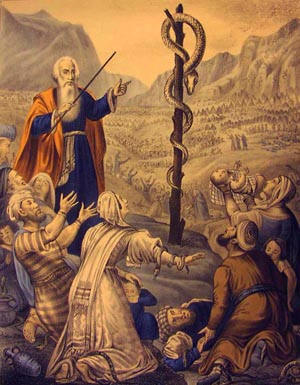

“Jesus answered him, ‘Are you the teacher of Israel and yet you do not understand these things? Truly, truly, I say to you, we speak of what we know, and bear witness to what we have seen, but you do not receive our testimony. If I have told you earthly things and you do not believe, how can you believe if I tell you heavenly things? No one has ascended into heaven except he who descended from heaven, the Son of Man. And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life.’”

-John 3:10-15

Jesus is speaking to an expert in the law, an authority on ethics and virtue. And yet Jesus doesn’t tell him that examining the beauty of the divinely-given law will help him to understand ‘heavenly things’. Indeed, despite a hobby of studying ethics, he doesn’t even understand earthly things. It seems that the heavenly world of perfect virtue and ideas is not accessible to anyone except Christ, the god-man. And Jesus’ first instruction isn’t to follow his gaze up into the heavens, but instead to look merely at him.

There are a few brilliant points of symbolism here. The form of Christ will be lifted up for all to see, like a banner on a high pole or a statue on a pedestal for all to admire. He will be put on display, but that lifting up will take the form first of crucifixion (Christ dying) and later of ascension (Christ leaving). And he recalls an episode from Hebrew history, too. The Israelites were dying of a plague of snakes which God sent them in punishment for their faithlessness. Moses prays that God will save them, and God tells Moses to make a giant bronze serpent upon a pole, and anyone who is bitten may look at the snake and be healed.

It’s counterintuitive. It’s not a vision of an antidote or righteousness or a cure placed upon a pole, but an archetype or model of the affliction. It’s hard to make sense of this, but a start would be remembering the truth that facing the worst of your suffering, head-on, helps the process of healing. “You gotta feel it to heal it”, a psychologist once said. He was right. In Tibet, people who die often receive sky burials, which is when you place your loved one’s body on top of a hill for the birds to eat. This seems grotesque, but Tibetans think it helps them come to grips with mortality – they’re forced to. None of this embalming, or keeping someone’s heart in jar like the Egyptians did. They’re much more at peace with the awful reality of death as a result.

Perhaps the same principle applies to sin. “You have to feel it to heal it.” The Bible asks sinners to repent, which we usually misinterpret as meaning we should just go out and change our behavior. To ‘repent’ primarily means to feel sorry about something bad you’ve done, to regret it. Why do we always think it means a change in behavior? Again, because we’re blinded by our fixation on our own doing. Changing our behavior puts us in control; regret does not. Alcoholics Anonymous has become a think-tank on how people change – how to alcoholics break their deadly addiction? A major crux of their Twelve Step program is Step 4, where they write out all the ways they’ve sabotaged relationships, all the ways that fear cripples their ability to live, and all the embarrassing or shameful sexual encounters they’ve had. In Step 5, they take that list and tell all of it to another person, which – on one interpretation – concretizes that dysfunction.

Martin Luther famously wrote that the Christian life should be one of repentance. So while looking up at visions of the good, the true, and the beautiful may be inspiring, it’s human nature to neglect the side of Christianity which asks us to stare at the bronze snake, to see sin for what it is. And so Christ, before becoming the glorified Lamb on the throne of Revelation 5, must first “be sin for us”, as Paul writes. And we look up at him, like the Israelites, gaze at the embodiment of human wrongdoing and guilt. And since Christ is not only “sin”, but also he is a new, archetypal man (Rm 5), we see ourselves in his guilt – our death in his death, and afterward (and only afterward) our life in his: “We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, so that as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life” (Rm 6:4). So this contemplation of Christ simultaneously allows us to see the sin within us, the afflictions that become our snakes, embodied in the one that is lifted up. Visions of the good are often naïve and premature, a substitute for contemplation of sin rather than something which properly afterward:

So too no created being can go out of itself by rational contemplation. Whatever it sees, it must see itself; and even if it thinks it is seeing beyond itself, it does not in fact possess a nature which can achieve this. (Gregory of Nyssa, Commentary on Ecclesiastes)

Reinhold Niebuhr once said that original sin is the only empirically verifiable Christian truth. It is also a starting-point for vision of the good, if we take Gregory of Nyssa seriously here. We cannot see outside ourselves the truth and beauty of the good, but we can see our own inability to see it – here our contemplative bronze serpent. Inability and rebellion, not the beauty of the law; blindness, not a vision of the good – this seems a more reliable starting-point, and it has deep biblical roots:

Abraham passed through all the reasoning that is possible to human nature about the divine attributes… and he fashioned for himself this token of knowledge of God that is completely free and clear of error, namely the belief that God completely transcends any knowable symbol. And so, after the ecstasy which came upon him as a result of these lofty visions, Abraham returned once more to his human frailty: I am, he admits, dust and ashes, mute, inert, incapable… (Gregory of Nyssa, Against Eunomius, both found in his From Glory to Glory anthology)

Thus faith becomes both the starting-point of Christian life and its sustaining force. Contemplating revelation is a good thing, but we do not enter a relationship with it until Christ is seen as rescuer. And for that, the death with Christ in guilt which we avoid, as well as the blindness and confusion we’re so tempted to deny, perhaps forms a firmer basis than visions of the good. Plato thought that virtue is learned by seeing a vision of the good, a vision we can recognize on account of our latent inner knowledge about transcendence. Søren Kierkegaard, as a Christian philosopher, takes issue and proposes a Christian way in which we learn knowledge about true virtue and about God, in his Philosophical Crumbs:

[A human] must therefore be characterized as beyond the pale of the Truth, not approaching it like a proselyte, but departing from it; or as being in Error. He is then in a state of Error. But how is he now to be reminded, or what will it profit him to be reminded of what he has not known, and consequently cannot recall?… The Teacher is then the God himself, who in acting as an occasion prompts the learner to recall that he is in Error, and that by reason of his own guilt. But this state, the being in Error by reason of one’s own guilt, what shall we call it? Let us call it Sin.

What now shall we call such a Teacher, one who restores the lost condition and gives the learner the Truth? Let us call him Saviour, for he saves the learner from his bondage and from himself; let us call him Redeemer, for he redeems the learner from the captivity into which he had plunged himself, and no captivity is so terrible and so impossible to break, as that in which the individual keeps himself. And still we have not said all that is necessary; for by his self-imposed bondage the learner has brought upon himself a burden of guilt, and when the Teacher gives him the condition and the Truth he constitutes himself an Atonement, taking away the wrath impending upon that of which the learner has made himself guilty.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply