When asked to describe Christianity in ten words or less, Will Campbell is known to have said, “We’re all bastards, but God loves us anyway.” I haven’t read much of his odd variety of work, but I will now. After passing in the spring of this year, the most recent issue of the Oxford American ran a tribute to the man, who was a real-life whisky priest, and a civil rights activist, and a Southern Baptist, and a Tennessee farmer, and a guitar player. Here’s what Hal Crowther had to say about his low backwoods church:

Later I had the good fortune to join Campbell’s extended congregation, a privilege that included pilgrimages to his home place in Mt. Juliet, Tennessee, where pastoral consultations might include drinking whiskey and listening to Will sing scabrous ballads to his own guitar accompaniment. Cussing and praying were not incompatible in his religious worldview, where the sacred and profane were as inseparable as God’s children, white and black and all shades in between. In Mt. Juliet no pilgrims were turned away, and none were confronted with their sins and errors. Will could homilize with the best of them, but he was just as comfortable listening, nodding benevolently, whittling away at the whimsical walking sticks he bestowed on his friends. Nonjudgmental? That’s not for me to say…he believed in the Gospel of Jesus Christ, put it like a coat that fit him and took it places where it hadn’t gone before. Of the many categories that included him–Christian, Southern Baptist, clergyman, theologian, liberal (even “redneck,” which he embraced cheerfully as long as it came without a Yankee sneer)–there was not one of which Will Campbell was even remotely typical.

…He wrote a score of books and won prizes for many of them, but not every chapter and verse of the Gospel According to Will was crystal clear to his adherents, not even to the most loyal and attentive. The writer John Egerton, who was Will’s close friend for decades and in later years served him as a kind of consigliere, admitted after Campbell’s death that the holy man’s logic sometimes escaped him. “I never understood a lot about him,” Egerton allows. “But he was no phony.” Particularly difficult for Christians of weaker conviction was Will’s insistence that Jesus forgave the worst criminals while their hands were still bloody, a radical belief that compelled him to counsel Klansmen and racist assassins, and to visit James Earl Ray, King’s murderer, in his prison cell. “Hate the sin, not the sinner,” is an ambitious moral goal to which many pay lip service…but Will Campbell made it the cornerstone of his faith. As he was quoted repeatedly, “If you’re gonna love one, you’ve got to love ’em all.”

The way Campbell saw it, only a small percentage of God’s children can ever find and steer their lives by the light of reason, but that didn’t exclude the rest of His children from the light of His love. Who, Will might ask, needs help–or love–more than a benighted, hate-poisoned Klansman? I could see the sense in that. But the old deep-water religion and the doctrine of universal amnesty were a harder sell to someone like me, the product on the one hand of four generations of Unitarians and, on the other, of untold centuries of vengeful Celts. But Will didn’t proselytize; he was a pastor, a shepherd, not an evangelist. If you disagreed with him, he only needed to be sure that you’d thought it through with care, that you hadn’t recycled some cheap piece of conventional wisdom. If you said something harsh or stupid in his presence, he’d look at you with mild disappointment, as if he’d just bitten into a sour apple, and with real concern, as if he was ready to help you if you asked him. Such was the agreeable flavor of his ministry.

The way Campbell saw it, only a small percentage of God’s children can ever find and steer their lives by the light of reason, but that didn’t exclude the rest of His children from the light of His love. Who, Will might ask, needs help–or love–more than a benighted, hate-poisoned Klansman? I could see the sense in that. But the old deep-water religion and the doctrine of universal amnesty were a harder sell to someone like me, the product on the one hand of four generations of Unitarians and, on the other, of untold centuries of vengeful Celts. But Will didn’t proselytize; he was a pastor, a shepherd, not an evangelist. If you disagreed with him, he only needed to be sure that you’d thought it through with care, that you hadn’t recycled some cheap piece of conventional wisdom. If you said something harsh or stupid in his presence, he’d look at you with mild disappointment, as if he’d just bitten into a sour apple, and with real concern, as if he was ready to help you if you asked him. Such was the agreeable flavor of his ministry.

It was a hard road Campbell set himself to travel, and he could be hard on himself. He warned me once about a bad person we both knew–I wish I had listened more carefully–but what tormented Will was not the trespass committed against him, but his uphill struggle to forgive the trespasser unconditionally. A friend described Will as “obsessed with grace.” He was one of a kind, a Dixie Diogenes navigating by his own light…Could we clone him, find a way to breed more of him, or was he just a rare gift from a tired gene pool–or as he might say (but never about himself), a manifestation of the grace of God?

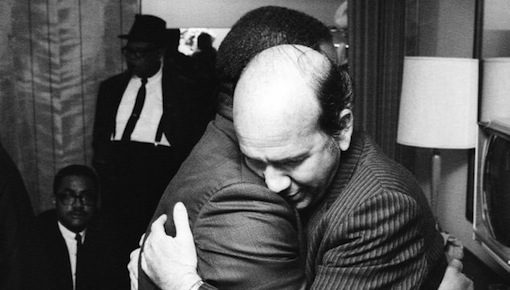

“Will Campbell was a sage,” eulogized Congressman John Lewis, a surviving hero of the civil rights movement. “He was a gift to America who never received the recognition he truly deserved.” Another admirer characterized Will as a “man of many disguises,” and as John Lewis and his colleagues remember him, he sounds almost like the Lone Ranger–wherever injustice and oppression soiled the Southland he would appear mysteriously, a black hat on his head and forgiveness in his heart. The day he was memorialized in Nashville, my wife and I held our modest memorial in the Yankee-haunted north woods, a service that consisted mostly of listening to gospel standards recorded by the late, great sinner George Jones, Nashville’s second most painful loss in the spring of 2013. “It is No Secret” was the one that choked me up: “With His arms wide open, He’ll pardon you…” (“It is no secret what God can do.”) Right, Will. Sometimes–this time, anyway–I think I get it.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9n7qzSqjFwQ&w=600]

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply