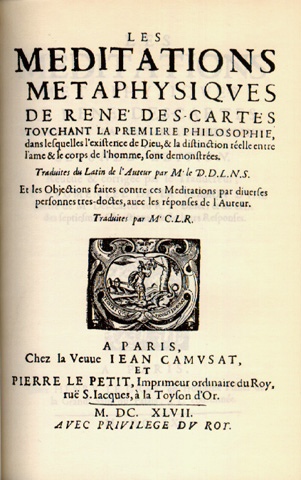

René Descartes has been called the first modern philosopher, a turning-point in how we think of ourselves and our world. His famous principle was “I think, therefore I am.” He wanted to find a sure foundation for all available human knowledge. Anxious to please the Jesuit academy he admired, he even proved God – all based on the reality of thinking, the idea that one cannot even doubt without proving, thereby, the reality of the person doubting. The mind is always true and, as a foundation and criterion for truth, is transcendent.

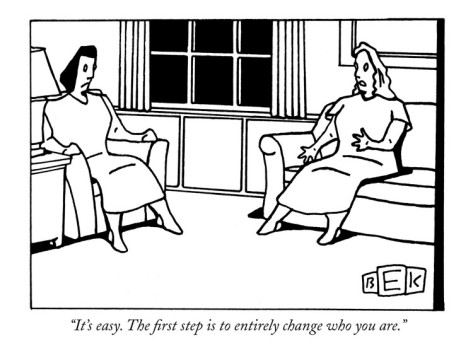

We’ve inherited his legacy, of course. As a child, I used to say ‘prove it’ whenever someone said something that annoyed me, and then replied ‘prove it’ to their proof, until at last whoever it was (usually my mother) would be exasperated enough to stop proving. But proof’s what we want; certainty’s what we thrive on. We may not think we can prove God, but we do think we can come close to proving the Resurrection, the reality of miracles, even what habits will form the best life. Inherent in this deductive, this knowledge-focused transcendent ‘I’, is the idea that our own ability to perceive things is the criterion of truth; truth is defined as the non-falsifiable or evidentially probable, etc. This way of looking at the world carries with it a disregard for psychology, literature or any other open-ended branch of knowledge – we want to deduce everything, to know it and be done with it. The rise of sociology as the scientific study of study aims to give definite form to the humanities, to subsume them into the controllable.

We’ve inherited his legacy, of course. As a child, I used to say ‘prove it’ whenever someone said something that annoyed me, and then replied ‘prove it’ to their proof, until at last whoever it was (usually my mother) would be exasperated enough to stop proving. But proof’s what we want; certainty’s what we thrive on. We may not think we can prove God, but we do think we can come close to proving the Resurrection, the reality of miracles, even what habits will form the best life. Inherent in this deductive, this knowledge-focused transcendent ‘I’, is the idea that our own ability to perceive things is the criterion of truth; truth is defined as the non-falsifiable or evidentially probable, etc. This way of looking at the world carries with it a disregard for psychology, literature or any other open-ended branch of knowledge – we want to deduce everything, to know it and be done with it. The rise of sociology as the scientific study of study aims to give definite form to the humanities, to subsume them into the controllable.

In the contemporary Church, this tendency shows itself in the temptation to interpret the Bible exhaustively, using the lexicon and concordance to prove the most ‘right’ inflection of a text. Of course, biblical texts often do lend themselves to this, but other modes of interpretation are better for some genres. Think of Revelation: we match notes up with Daniel, work out the meaning of the different trumpet and bowl judgments, debate pre- and post- and a- millennialisms or chiliasms. We want to work knowledge out and hold it in our hand; in this the Christian Church has given itself over to the worst of the modern bias toward science (i.e., proof, deduction) far more surely than in the embrace of evolution or any other ‘topic.’ The damage the scientific worldview has done to religion rests in its methodology, not its content. The early church read Revelation, or rather listened to it, as a letter to be read aloud cover-to-cover in church; the literary imagination, not meticulous deduction, was the tool for engaging it.

The need to work out and accumulate certain, unchanging, fixable knowledge is itself a form of law, exhibiting all the common psychological impulses in our obsession with self-justification: the denial of death by fixing ourselves to something permanent; the need for control because it is beneath us, dependent on our perception; the desire to return to Eden prematurely by circumventing the ‘futility in their thinking’ asserted by Paul. It’s not putting knowledge in the place of God that’s idolatry; it’s drawing religion down into the realm of the knowable, the predictable and manageable. In terms of the fallout, the problem isn’t so much that we develop bad hermeneutics (though it is that), but rather that the weight of self becomes too much to bear; it’s one more place where religion turns into self-justification, the burden of which “is intolerable.”

There’s another place I see this as particularly harmful: worship. I still subconsciously try to evoke certain emotional states in myself during worship; I crave a feeling of unity with God when I take communion. Like Descartes, the value of things can only be affirmed by their reference to the indubitable ‘I’. So I want to observe myself becoming more virtuous, more sanctified; want to feel myself united with God in worship. These results are of course a wonderful gift when given; but a source of Law nonetheless – they make us ask what we can do better to achieve these things. Performancism, again: predicated on what we can see, feel, know and, therefore, control. In the impasse, though; in suffering, we may be in the dark, powerless to manage or predict. It’s only when we realize the ‘I’ is in fact the least certain, the most unreliable thing – and that this alone represents the possibility for its redemption – that the world looks more like gift, less like achievement. Any attempt to achieve even spiritual passivity and receptivity is the death-throes, the frantic desperation to survive, of the Old Adam. This openness, the submersion of the self, only comes in flashes, and must happen to us – anything else would be a contradiction. Thank God that it does happen, and is always (only) given freely.

COMMENTS

4 responses to “Theology Thursday: The Law of ‘I’ and the Grace of God”

Leave a Reply

Good post. Really appreciate the paragraph on worship. I sometimes catch myself wondering what I need to do to be experiencing more.

Yet another important piece. Thanks Will.

Cannot agree more. Amazing piece. Thanks Will.

This is excellent. I really appreciate you interacting with modern approaches to biblical studies.