The New York Times Magazine’s cover piece for this past week is a rejoinder to one from 2003, about mothers “opting out” of ambitious, lucrative career fields, to become stay-at-home mothers. This time, ten years later, Judith Warner catches up with and spotlights three women in particular who want a way back into their careers, and the picture given is definitely (and mercifully) mixed. Of the three women, one is divorced and living in a condo, one is living her dream as the CEO of her own non-profit, and another just lost her new job, worrying how the kids will afford college.

The New York Times Magazine’s cover piece for this past week is a rejoinder to one from 2003, about mothers “opting out” of ambitious, lucrative career fields, to become stay-at-home mothers. This time, ten years later, Judith Warner catches up with and spotlights three women in particular who want a way back into their careers, and the picture given is definitely (and mercifully) mixed. Of the three women, one is divorced and living in a condo, one is living her dream as the CEO of her own non-profit, and another just lost her new job, worrying how the kids will afford college.

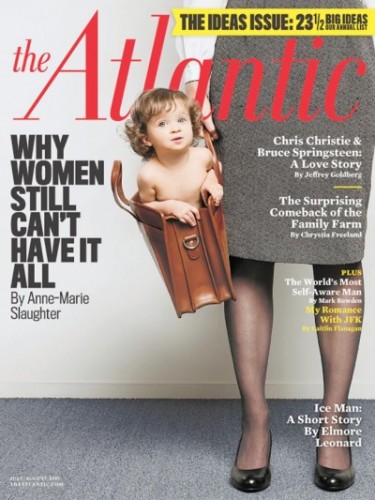

It is a timely exposé: The Atlantic’s thread from this time last year—deviously titled “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All”—asked some of the same questions about the mythologies of “success” that plague today’s women. While I’m not a mother or a parent, or a woman, even; I am the son of a 9-to-5 mother, and a human being who has had a family, and anyways, it seems that the questions have extended from gender rubrics to the Life Rubric. In seeing these women, as opters out opting back in, what lifestyle narratives are informing a change of heart (if there is such a thing)? What is being said about the contemporary home, that traditional nucleus, and its relationship with the workplace? And what is ambition’s place in the face of the contemporary “life well-lived”?

Sheilah O’Donnel, one of the women covered in the story, believed that coming home would solve some of the marital strife that was only getting more serious with her promotions at work. Instead, quitting it all and being a mother became something of an identity crisis, and a sense of “personal dislocation set in.”

But the tensions in her marriage didn’t improve. The couple’s long-term issues of anger, jealousy and control got worse as O’Donnel’s dependency grew and a sense of personal dislocation set in. Without a salary or an independent work identity, her self-confidence plummeted.

“I felt like such a loser,” she said. “I poured myself into the kids and soccer. I didn’t know how to deal with the downtime. I did all the volunteering, ran the auctions. It was my way of coping.”

Five years after leaving her Oracle job, O’Donnel began volunteering for Girls on the Run, a nonprofit group devoted to girls’ emotional empowerment and physical well-being, and was eventually hired part time, at low pay. She loved the work. The organization’s message, about respecting yourself and surrounding yourself with people who appreciate you, resonated with her. “I started feeling very devalued when I was with him,” O’Donnel said of her husband, “but when I was doing all this nonprofit stuff, I felt great.”

O’Donnel and (her husband) Eisel agree the job drove a destructive wedge between them. “I look back on it as the beginning of the end of our marriage,” Eisel said when we talked by phone last month. “Once she started to work, she started to place more value in herself, and because she put more value in herself, she put herself in front of a lot of things — family, and ultimately, her marriage.”

…What had been a nasty divorce was entering its end stages and the “60 Minutes” interview had come up. When O’Donnel saw the video again, the image of her younger self, giving up her job and proclaiming the benefits of staying at home haunted her. “I was this woman who made this great ‘choice,’ ” she said, sadly. “It wasn’t the perfect fairy-tale ending.”

Like anyone, there was the tendency to opt out of one rat race to find oneself opting in to another. One thing seems certain, that O’Donnel’s reasons for “opting out” of the workplace—however attractively valid or noble the reasons were—could shroud her real desire to be back in the office for only so long. This was the case with each of the women’s stories, that even after making the decision to stay home, they each worked, in some capacity, to maintain what professional strand of themselves they believed to be their identity. While seeking, for various reasons, to be a stay-at-home mother to their children, the opt-out narrative of the “liberation of giving up work to stay home” did not seem to liberate at all. Instead, what had been in the basement came upstairs: the marital and parenting issues from before metastasized into resentments, and new feelings of inequality suddenly surfaced when there ceased to be a salary or an “independent work identity”.

Carrie Chimerine Irvin, on the other hand, felt the same resentments about the career gaps in her home, and remembered feeling like she was in “an unequal marriage” with her husband. Unlike O’Donnel, though, she found encouragement from her husband when she brought up going back to work. Now she runs her own educational nonprofit and continues to pick the kids up from school, doing more than she ever thought possible, and not in a good way:

She acknowledged that what she was trying to do was impossible. “The pace at which I’m living right now is unsustainable,” she told me. She tried her absolute best to cut things that weren’t strictly essential. She almost never saw friends, rarely exercised and was trying to trick her body into running faster on fewer hours of sleep. Something had to give — and, unfortunately, that something was shaping up to be time with her husband.

When I visited her one morning this winter after her children and husband had left for the day, she told me that in their early years, she and Stuart traveled to Japan, shared books, interests and ideas. Even after their daughters came along, they had been sure to find ways to spend time together as a couple. They watched TV for a precious hour or so of decompression each night, after the girls went to bed. They talked together late, digesting their days. By this winter, however, they spent their evenings on separate floors, she downstairs in the kitchen, on her computer, catching up on the work she missed during her hours of caring for the children; he, upstairs, watching TV alone.

Carrie said the situation was in many ways unfair: she had been able, twice, to live her dreams, with her husband’s encouragement, first as an at-home mother, then as a start-up visionary, while Stuart’s steady job made it all possible. And he had to adjust to the loss of her attention when she first shifted it to their daughters and then to her new job.

Their situation was common enough among middle-aged, overtaxed, professional working parents. Stuart was hardly the first man to find himself sidelined either by his wife’s devotion to her children or her dedication to work or both. But knowing that their story was playing out in households all around them didn’t make their readjustment to life as a working couple any easier. “I think a big issue is that we both want to be taken care of at the end of the day, and neither of us has any energy to take care of the other,” Carrie said. “It’s the proverbial ‘meet me at the door with a martini and slippers.’ Don’t we all want that? A clean house and someone at the door? I think when I wasn’t working I had some guilt that that wasn’t me, but now I want to be that other person. . . . When you’re absolutely exhausted, it’s hard to be emotionally generous.”

Here we change gears, and find the complicating wedge—that really has nothing to do with gender roles, per se—between the myth of self-fulfillment and the elemental character of family (i.e. un-conditional love). While alluring, the individualism implicit in self-fulfillment is a non-renewable resource. More than this, the freedom it offers is a paltry freedom at best, because it is the product of our own dull ambition. And it still isn’t self-sufficient. It just hides its dependencies. Wendell Berry says,

There is a paradox in all this, and it is as cruel as it is obvious: as the emphasis of individual liberty has increased, the liberty and power of most individuals has declined. Most people are now finding that they are free to make very few significant choices…The net result of our much-asserted individualism appears to be that we have become “free” for the sake of not much self-fulfillment at all.

This is not to say that “freedom” and “fulfillment”—or its antecedents: worthwhile work, a home, a salary, a nice meal—are misguided ends. Not by any stretch. But, while ambition and self-fulfillment must be asserted from and directed within, true freedom and fulfillment, in the vocabulary of the family, must come from one’s inclusion into and sacrifice for something not-you. Marilynne Robinson calls home “solace”:

Imagine that someone failed and disgraced came back to his family, and they grieved with him, and took his sadness upon themselves, and sat down together to ponder the deep mysteries of human life. This is more human and beautiful, I propose, even if it yields no dulling of pain, no patching of injuries. Perhaps it is the calling of some families to console, because intractable grief is visited upon them. And perhaps measures of the success of families that exclude this work from consideration, or even see it as a failure, are very foolish and misleading.

So what is The Successful Mother, The Successful Family? Here it is not the question of whether the father or the mother or the child can “have it all.” No one here has anything but the gift of presence. This may make no sense, because outside of the family we operate in the realms of task-efficiency and accomplishment, but a family is never “accomplished.” No college graduation, wedding, or funeral ever seals a family member off for good. A family–elementally, not always practically–is the gift of permanence. It is a haven away from accomplishments, costs and benefits. It is that place we all want, “a clean house and someone at the door.” As Robinson says, the home is solace, a place of welcomed personal re-location in our selfsame worldly dislocation.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply