This one comes to us from Win Bassett:

Beck Hansen, better known as “Beck,” will forever be linked to the decade when MTV actually played music videos, kids lived for TGIF programming, and pogs were worth their weight in gold. Who in Generation Y doesn’t count Beck’s “Loser” as one of the first pieces of art to leave a permanent watermark on our young minds? Who isn’t brought back to afternoons of rollerblading and feeding our Tamagotchis every time we hear the low, throaty rumblings of what may have been our first introduction to the Spanish language? (“Soy un perdedor. I’m a loser baby, so why don’t you kill me?”)

I’ve never associated Beck or his music with religion, despite such tracks as “Lord Only Knows” on the 1996 Grammy-winning Odelay:

You only got one finger left

And it’s pointing at the door

And you’re taking for granted

What the Lord’s laid on the floor

The big single from the same album, “Devils Haircut”, also evokes Biblical allusions.

And everywhere I look

There’s a dead end waiting

Temperature’s dropping at the rotten oasis

Stealing kisses from the leprous faces

Commenting on the inescapable melancholy and blues of this song and touring life via the folklore of Stagger Lee, an African-American pimp murdered in the late 1890s, Beck says he used “this Lazarus figure to comment on where we’ve ended up as people. What would he make of materialism and greed and ideals of beauty and perfection?” And over a decade later, Beck wrote and performed “Heaven Can Wait,” a song that tackles the dualism of existentialism and the divine, for Charlotte Gainsbourg’s first album. (“Heaven can wait and hell’s too far to go/ Somewhere between what you need and what you know.”)

A quick look at Beck’s family history reveals that the influence of faith in his work should come at no surprise. In an interview with zine author Barbara Rushkoff, Beck describes his Jewish roots. “It’s all on my mother’s side. My mother’s mother was all-Jew,” he says. “Eastern European Jews. It runs through the female side of the famile [sic].” Though he wasn’t “Bar Mitzvah’d,” Beck briefly attended Hebrew school. “I got some of the Jew-knowledge, I just didn’t get the ceremony,” he admits.

More recently, Beck has quietly embraced Scientology. When asked if this particular religion is a part of his life, Beck told Vulture at the end of 2012:

“Yeah…, people in my family do it. I’ve read books, and I’ve learned about it. I mean, what I’m doing—I have a job, raising kids, I have friends, I have my interests, so I think my life is pretty full. I’m not off doing some weirdo stuff.”

I don’t have the audacity, or the naivety, to comment on another person’s devotion to his or her beliefs, but I doubt anyone will question Beck’s rather laissez-faire profession to L. Ron Hubbard’s legacy. Regardless of his devoutness to Scientology’s teachings, his most recent project, Sound Reader, invokes a model often associated with the canonical text of Judaism and Christianity.

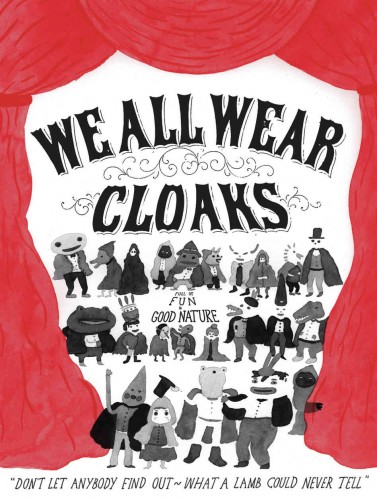

McSweeney’s, the publishing house run by Dave Eggers and best known for the Believer and Lucky Peach, has produced Beck’s latest album, “twenty songs existing only as individual pieces of sheet music, never before released or recorded.” Song Reader, which can “only be heard by playing the songs,” puts the listener in full control of the experience. “[B]ringing them to life depends on you,” announces McSweeney’s, much like the personal approach to Scripture adopted by Anglicanism—“what the Bible says must always speak to us in our own time and place.” In other words, a Bible gathering dust on the shelf doesn’t do a lot of good, and a pile of Beck’s sheet music lying around is similarly useless.

McSweeney’s, the publishing house run by Dave Eggers and best known for the Believer and Lucky Peach, has produced Beck’s latest album, “twenty songs existing only as individual pieces of sheet music, never before released or recorded.” Song Reader, which can “only be heard by playing the songs,” puts the listener in full control of the experience. “[B]ringing them to life depends on you,” announces McSweeney’s, much like the personal approach to Scripture adopted by Anglicanism—“what the Bible says must always speak to us in our own time and place.” In other words, a Bible gathering dust on the shelf doesn’t do a lot of good, and a pile of Beck’s sheet music lying around is similarly useless.

He writes in the preface to Song Reader, “They were all from a world that had been cast so deeply into the shadow of contemporary music that only the faintest idea of it seemed to exist anymore.” Beck could have been commenting on books of the Bible just as easily as he did on old sheet music he had collected. He continues:

Songs have lost their cachet; they compete with so much other noise now that they can become more exaggerated in an attempt to capture attention. The question of what a song is supposed to do, and how its purpose has altered, has begun to seem worth asking.

And just like that, Beck depicts the state of not only Christianity but many other prevailing religions in the United States. Their core teachings struggle to remain relevant in a culture in which only the fanatical seem to maintain our ever-shortening attention spans. Putting the Westboro Baptist Churches and terrorists from all creeds aside, what are the everyday faithful supposed to do? How has the commotion altered things for those who understand their purpose as having to do with the revealing of truth?

In perhaps a moment of prophetic foreshadowing, Beck reportedly told LA Weekly in 2000, “[O]ne of the things I love about Judaism is that it gives 100 different interpretations of a single line of Torah.” This week, a group of musicians in North Carolina will perform Song Reader in “the first time that all of the material will be arranged by one composer.” The performance in Raleigh won’t be the first time the album has been played, but it will be one more unique version of Beck’s project “brought to life—or at least to remind us that, not so long ago, a song was only a piece of paper until it was played by someone. Anyone. Even you,” as Beck ends his preface.

Søren Kierkegaard, who would celebrate his 200th birthday this week, similarly recommended this highly personal approach to other pieces of paper. “When you read God’s Word, you must constantly be saying to yourself, ‘It is talking to me, and about me.’”

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g_oWloXtK-g&w=600]

Win Bassett is a writer, lawyer, and entering Yale Divinity School student. He is a regular contributor to The Huffington Post and has written for Sojourners, Patheos, All About Beer Magazine, BeerAdvocate Magazine, Beer West Magazine, Serious Eats, and other publications. He has forthcoming pieces in Books & Culture, Religion & Politics, Publishers Weekly, and Indy Week. You can find him at http://winbassett.com and on Twitter at http://twitter.com/@winbassett.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply